For a multitude of reasons, I contend that science fiction is more progressively impactful than any other genre. For my article here, I want to focus on a couple of key theories for why science fiction is such a progressive genre and then look at what are in my mind some of the most important progressive science fiction films of the 21st Century.

To begin, celebrated science fiction studies scholar Darko Suvin famously articulated science fiction’s most fundamental role: “SF is, then, a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment” (20 Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On Poetics and History of a Literary Genre). In other words, science fiction “estranges” us from our reality and gives us an “alternative” reality in which to compare and scrutinize our own reality.

In the case of utopian representations, we can contemplate that alternative reality as a desired way of being. In the case of dystopian representations, we then see our reality in all its dysfunctionality and self-destructiveness, and, then, hopefully, change course.

More generally, science fiction studies scholar Phillip E. Wegner articulates the deeply pedagogical and revolutionary potential of science fiction:

Science fiction in this affirming vision is understood to be a form, not unlike the works of Homer or Shakespeare, that delights and teaches, conveying through popular narrative forms the most significant truths. Science fiction is also one of what I name…the evental genres, teaching its audience new ways of thinking about history, and brushing against the postmodern and neo-liberal commonplaces that drill into us the myths that history is finished, fundamental change is impossible, and there are no alternatives. Science fiction encourages us…to glimpse once more the infinite possibilities that surround us, and to recall our immense collective capacity to make new worlds. It is precisely these lessons that make science fiction…so threatening to the reigning concern. (His italics, 230-231 Shockwaves of Possibility: Essays on Science Fiction, Globalization, and Utopia)

In what follows, I will look at what I consider the most important 21st Century progressive science fiction films, films that exemplify these ideas, how these films “estrange” us from our own reality, thereby giving present day issues more accentuation, indeed, bringing clarity to the root causes of our most pressing issues, and, most importantly, open up alternative ways of being and alternative historical directions.

(Spoiler alert! I assume you have seen these films.)

Snowpiercer (2014, Joon-ho Bong)

Wegner also posits a connected theory to the above, how science fiction can teach us something about our present globalized capitalist world order:

One of the fundamental and less commented upon lessons of Suvin’s work is that, from its emergence in the late nineteenth century, science fiction represents a significant global modernist practice, its estranging visions of other cognitive worlds providing a way of bringing into focus the dramatic transformations and conflicts that define the experiences of an imperialist capitalist modernity and its world system. (14 Shockwaves of Possibility: Essays on Science Fiction, Globalization, and Utopia)

I think no film realizes all the above more so than the remarkable Snowpiercer. In short, Snowpiercer does that, “bring into focus…an imperialist capitalist modernity and its world system.” Director Joon-ho Bong has explicitly stated as much suggesting that if “humans are doomed to wreck our own habitat…that it’s not humans per se, but capitalism that’s destroying the environment”.

That is Bong’s core focus, giving us an allegory for capitalism. As Marxist scholar Fredric Jameson has suggested, we need an aesthetic that “reinvent(s)…possibilities of cognition and perception that allow social phenomena once again to become transparent, as moments of the struggle between classes” (212 Afterword in Aesthetics and Politics). Most indispensably, Snowpiercer especially does that, draw attention to “the struggle between classes,” singular in mainstream cinema these days.

Snowpiercer does more than that, though, it gives us the present-day realization of what capitalism is today. A “transnational globalized capitalism,” creating a “planet of slums” (from the title of Mike Davis’ extraordinary book Planet of Slums) where more and more people are sequestered, compartmentalized into “slums.” That is, the allegory of Snowpiercer is more than just “cognitively mapping” capitalism in general but also “cognitively mapping” our globalized capitalist state of being in particular. A state of being where a “transnational capitalist class” has no allegiance to a particular nation-state but rather is an island onto itself, hording the wealth of the world, while more and more people are being pushed to a marginalized (“planet of slums”) existence where they simply struggle to survive. The front section occupants of the train allegorically figurate the former while that latter is represented by the tail end section occupants of the train.

The film’s allegorical depth goes even deeper than that, registering the (still!) fallacy of “the social Darwinist idea that a class hierarchy is natural and normal. That lower Others (lower/working class in this case, though of course this disturbing ‘sociopolitical’ hierarchical ‘measurement’ has been historically used to keep other Others – especially people of color and women – buried at the bottom of a sociopolitical well) are born into their ‘preordained’ and fixed station in life, and that a ruling elite is necessary to run the world” (Reagan Ross).

By preceding the events of the film with a climate change apocalypse, Snowpiercer links climate change with capitalism, a causal connection supported by many scholars. Finally, the ending note of Yona and Timmy, markedly Asian and African American, suggests a radical shift in being, a movement not just towards a new birth of humanity based on diversity but also to a utopian alternative to capitalism itself.

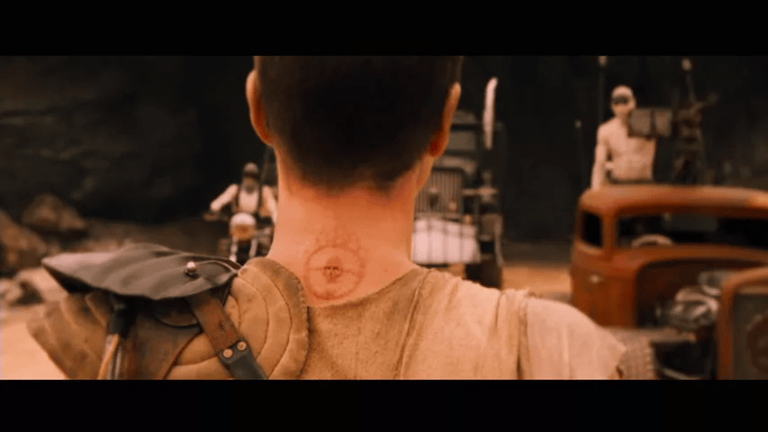

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015, George Miller)

To my mind, Mad Max: Fury Road is both a feminist film and a film that boldly points a finger at “who killed the world” (or, who is killing the world) which we ostensibly get in this exchange between the escapee women and Nux (Nicholas Hoult):

Nux: “He is the one…who grabbed the sun.”

Splendid: “Look how slick he’s fooled you war boy.”

Capable: “He’s a lying old man.”

Nux: “By his hand…we’ll be lifted up.”

Splendid: “That’s why we have his logo seared on our backs! Breeding stock! Battle Fodder!”

Nux: “No, I am awaited!”

Capable: “You’re an old man’s ‘Battle Fodder’!”

Splendid: “Killing everyone…and everything.”

Nux: “We’re not to blame!”

Splendid: “Then who killed the world?”

The “who killed the world” line here seems to point to kingpin Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne). Add in that all the baddies are men and most of our heroes are women, and we can begin to see who director George Miller is targeting here.

However, with the symbolic elements and the metaphors in the film, I would argue that Miller’s aim is less men than patriarchal, phallocentric, hypermasculine (toxic masculinity) ideologies. The specific references in the exchange above speak to these ideologies. An authoritarian figure, Immortan Joe gained his following through making himself a figure head. Indeed, he essentially enslaved his followers (“searing his logo”) to serve his purposes, which means he objectifies men by turning them into disposable bodies (“Battle Fodder”) and he objectifies women for his sexual/procreative needs (“Breeding Stock”). In terms of the latter, Immortan Joe keeps the women – he degradingly calls them “breeders” – in a vault, equating them with “treasure,” his property.

The women reject this objectification, saying, “We are not things.” Most glaringly, we get an extremely disturbing image of women getting their breasts pumped for their milk, associating them with livestock. That then gets to the real progressive deep element of this film, not “who” but what killed the Earth?

Intersecting with this finger pointing of patriarchy phallocentrism, hypermasculinity is what I would argue is a finger pointing to capitalism as well, which is a patriarchal, phallocentric ideology, e.g., a predacious, avaricious, survival of the fittest ideology.

Many signifiers in the film suggest this focus, such as how the villains consume human bodies – e.g., the “War Boys” need the blood of Others to survive – and how we see human bodies used as what amounts to slave labor (the many ways we see bodies used as machines that make this society go).

The most telling support of this reading is how the allegorical capitalist (e.g., Immortan Joe) controls the wealth of this society, in this case, the source of wealth and power being water.

Finally, that Splendid uses the term “logo” also signifies how Immortan Joe’s possession of Others (e.g., women) is signified by this remnant from another time, corporate power and its tendency to put its “logo” on everything and/or how corporate power commodifies (objectifies) everything and everyone.

In this way, Mad Max: Fury Road perfectly realizes Suvin’s dictate that science fiction “estranges” us from our own reality, giving us a reality that holds up a mirror of what our reality is. A reality where these toxic ideologies are literally “killing” (consuming) the world.

The film also gives us an alternative future, where toxic ideologies (patriarchy, phallocentrism, hypermasculinity, authoritarianism, capitalism) are rejected, which is especially punctuated by the water freely and equally distributed to the people and where women and the working class are empowered and agentic.

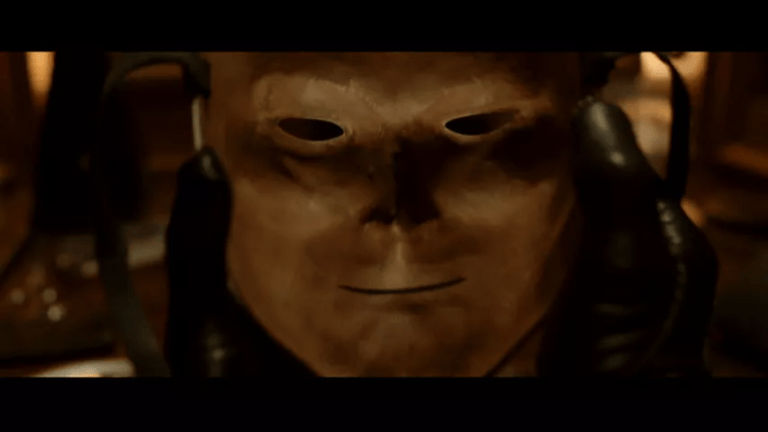

V for Vendetta (2006, James McTeigue)

As I say in my write-up of V for Vendetta, the film “is like a Rosetta Stone for both a vision of what a worldwide dystopian authoritarian rule looks like (as it also informs present day authoritarian tactics here in this country and around the world) and the various manifestations of the crucial force of resistance” (Reagan Ross).

Released during the George W. Bush administration, we can see how the film reflects many of the tactics and propaganda that this administration (and the right-wing in general) used to both manufacture the Iraq War and then justify its endless “war on terror”. For example, appealing to adversarial emotions, such as the fear and hate of Others (“immigrants,” Muslims, LGBTQ people, activists, etc.); toxic ideologies, such as patriotism, hypermasculinity, and racism; religious beliefs (“godlessness”); and using media propaganda strategies (cherry picking, card stacking, ad hominem attacks); manipulative language and ideas (doublespeak, euphemisms, exaggeration); and packaging lies in highly sophisticated “truth” packages.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Minority Recognition in Film: Where is the diversity?”

“How a film about human trafficking was made”

“How a film about human trafficking was made”

V for Vendetta also gives us a model for resistance, not just in the visage of V himself or the enlightened Evey, but the populace in general as they finally rise up against fascism.

The ending image of the citizenry rising up, dressed like V, marching toward the parliament building emphasizes the film’s didactic solidarity message as well: Unlike most hero narratives, where the hero “saves” the day, V becomes an “idea” that inspires the people to act for themselves. And that’s the final message of the film: Like the people in the film, people everywhere need to rise up and resist authoritarianism and hate.

What happens next in the film adds depth to this vital message: The resisters take off their “V” masks, again stressing their collective individualities (and the film further underscores this by bringing back all of the oppressed characters in the film). As opposed to what happens under Chancellor Sutler’s fascist government, where conformity and homogeneity are the rule, true diversity breaks down the self/Other divide, breaks down hate, which, in turn, leads to a collectivity of selves not Others, a true utopian sensibility.

Conclusion

Ethnic and Race Studies Historian Nikhil Pal Singh nicely gets at why the very concept of nation states and national identities are ideological (e.g., a product of normative indoctrination):

“[The] story of nationhood must be told over and over, because there is nothing natural about the nation or the fashioning of its predominant civic identities. Nations… [are] lived primarily through the techniques of narration and representation.” (19 Black Is a Country).

In other words, nations and national/ethnic/racial identities are not some natural and normal (innate) way of being but are in fact created or constructed via dominant discourses, such as historical, political, and ideological narratives and fictional representations.

In effect, this indoctrinated way of being is our reality, and as such it is harder to see the ingrained injustices, iniquities, and overall oppression going on everyday all around us. Science fiction cures this lack of seeing, by doing what Suvin and Wegner convey above, “estranging” us from our reality. Thus allowing us to see more clearly the toxic ideologies (patriarchy, hypermasculinity, capitalism, authoritarianism) that inform our reality, thereby “teaching” us to contemplate new horizons of being, alternative historical directions.

That is why these science fiction films that I have highlighted here are so important, because they do that, reveal our (self) destructive way of being and, in some cases anyway, offer us alternative (utopian) directions.

*In the second part of this article (“The Self/Other Divide: Science Fiction Films That Focus on AIs, Cloning, ‘Third World’ Labor, and Immigration”), I will focus on Ex Machina, Never Let Me Go, Moon, Sleep Dealer, and Children of Men.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter. Photo Credit: Allessio Ferretti on Unsplash