Article in collaboration with: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) seeks to address the increasing challenge of global warming and declining food security on agricultural practices, policies and measures through strategic, broad-based global partnerships.

Article in collaboration with: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) seeks to address the increasing challenge of global warming and declining food security on agricultural practices, policies and measures through strategic, broad-based global partnerships.

How I work on anticipatory climate governance to help countries deal with climate change.

It might have happened to you already. That moment when you imagine in full color the damages the weather may cause. For some people in Central America, more and more often, it’s when crisis kicks in: the river that took away their house, the drought that destroyed the harvest, the flood that inundated the town. For others, something happens around us that makes us realize what the future may be like if extreme weather events persist. It can be a news piece, a post on social media, or a photo that triggers the Matrix effect in our mind and makes us see how everything is connected, that climate, directly or indirectly, will impact every aspect of our life, our societies, and countries.

The efforts to imagine challenging futures where we can transform our societies and coexist with climate change are more frequent now that the international community, governments and citizens are aware of the urgency of climate action. That’s what I do in my job. I work with governments to explore what their country could be like in the future, mainly the aspects that are still uncertain and related to climate management. In this space we work jointly with other leading actors, such as entrepreneurs, researchers and farmers—sometimes with very contrasting opinions between each other. The image above is part of that process.

Together, they look for answers to questions like what kind of food are we going to eat in thirty years? Where will they be produced? How are we going to handle the water shortage? How are we going to achieve decarbonization of the economy if at this moment we are dependent on oil? What challenges could we encounter along the way and what opportunities will there be to combat them?

Related topics: Can Greta’s Straight Talk Bring Moral and Financial Responsibility Into the Climate Conversation? – Investing in the future: youth-led research and its role in combating climate change – Insects Armageddon Caused by Climate Change

The idea of these exploratory exercises is not to predict what is coming; the future is uncertain and that cannot be changed. However, anticipating and analyzing the elements that influence these uncertainties help to make decisions. It helps to understand what has not been taken into account when creating policies and strategies to manage climate change and what assumptions about the future must be adjusted to achieve transformational changes.

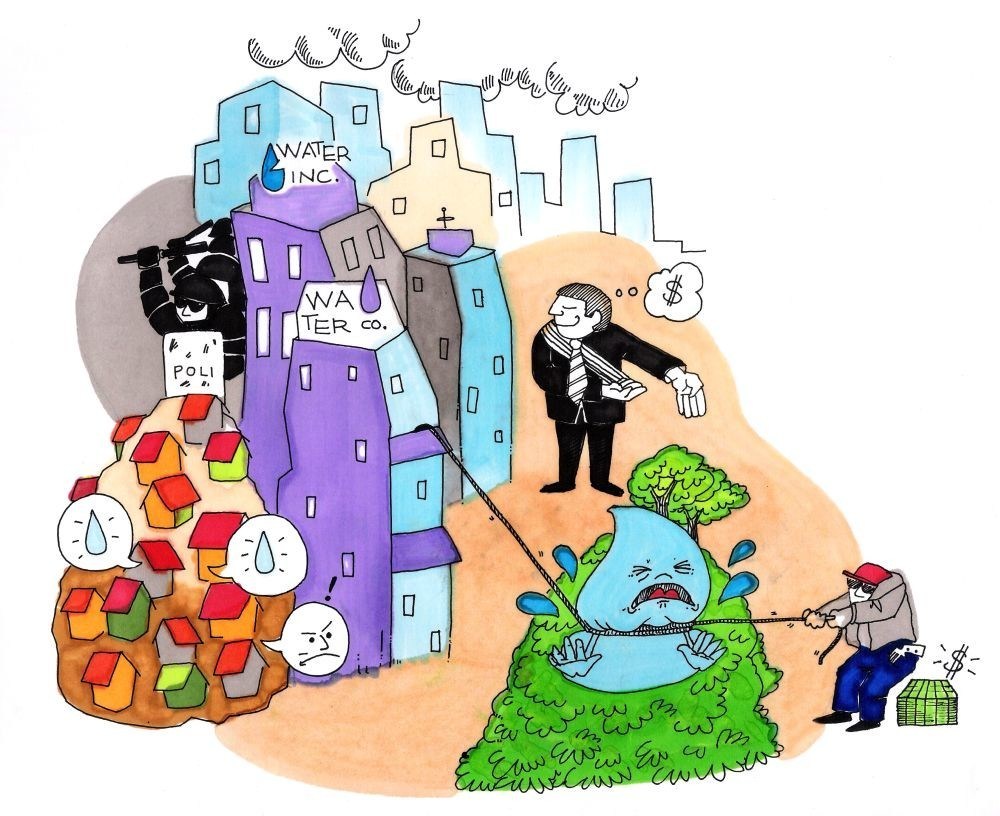

Illustration of the scenario ‘Se descompuso Tere’. Credit: Laura Astorga

The challenge is that these explorations of the future should not only deal with climate. Climate change will make it more complicated to estimate the timing and intensity of periods of drought and rain or extreme events such as hurricanes. However, we also don’t know in what conditions the countries will be in order to respond to these incidents, and even less if they will be effective in doing so. There are many other challenges to face, such as the disruption of the labor market, the fourth industrial revolution, migration, aging population and the decline of biodiversity, to name a few. The weather only complicates them. This makes the efforts of countries to adapt to the climate and mitigate its effects even more challenging. The complexity of commercial, economic, natural, political and social systems makes it difficult to predict how countries will address climate change.

This is when we can bring the future to the present. magining how some of these uncertainties may evolve in our countries gives us clues about the decisions and actions to be taken in the present. By doing this, we can improve our resilience to climate change.

There lies the essence of what we call anticipatory climate governance. This is the anticipation of uncertain climate futures and the use of knowledge acquired in the present to manage climate phenomena. This type of governance gathers methods such as the creation and modeling of future scenarios, environmental impact assessments, climate projections, vision exercises, and vulnerability and risk studies.

In Latin America we have been working on this topic for more than five years. The processes that we designed and implemented with the governments of Costa Rica, Honduras, Peru and the Central American Integration System (SICA) have been great lessons for the research that is done on this global practice, still emerging.

One of the lessons we’ve learned is that exploring future scenarios can be a useful tool when a country is clear that their path must be radically different. Something recurrent in the cases we support is the feeling that the usual planning methods are obsolete for these more complex problems.

Illustration of the scenario ‘Tormenta sin Agua’. Credit: Laura Astorga

For example, in 2015 when the Costa Rican government defined how much greenhouse gases (GHGs) were going to be reduced in the following 85 years, to present at the COP21 in Paris, it realized that the method established by the international community to define that goal did not give the results they wanted. They were not ambitious enough. They then opted to complement this methodwith a participatory process of consultations where four future scenarios were created for 2050, together with key actors from emitting sectors such as producers, livestock breeders and representatives of industry chambers.

The process helped to understand which strategies to reduce emissions were going to be effective, which ones were not, and how they should be adjusted. In the ‘Hipster Republic’ scenario, the social pressure of citizens to the State results in an efficient public transport network, while the StormWithout Water’ scenario warns of the dangers of favoritism when water sources end up in private hands. In the ‘Decomposed Tere’ scenario the country’s energy matrix has returned to fossil fuels as hydroelectric dams ran out of water. Through this creative process of imagination and analysis of plausible futures, the government was able to confirm that key actors of the largest emitting sectors of the country had even more ambitious proposals than those that already existed, and that the challenging goal that they have in mind was going to be achieved. Months later, the Paris Agreement was signed, through which Costa Rica ratified its global leadership in environmental, social and climatic terms.

While we are learning about the plausible climate futures, we also realize what still needs to be done. We would love to see that municipalities, communities and national governments facilitate and lead these processes, thereby increasing their e resilience towards changes in climate and their surroundings. Therefore, training in scenario development is on our list of priorities for the coming years. On the other hand, at the level of science there is still much to understand about the political aspects of anticipatory governance. For example, when making decisions about the climate, who defines what the future will look like? When they do that, who is involved? How do those ideas about the future influence policymaking? In our global research project RE-IMAGINE, my colleagues and I are giving answers to these questions and opening up debate to improve climate governance in the worlds most vulnerable regions.

About the author: Marieke Veeger is a Scenarios and Policy Researcher for the CCAFS at the University for International Cooperation (UCI).

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Photo Credit: Illustration of the scenario ‘Hipster Republic’. Credit: Laura Astorga