To feed the world, we need to pay more attention to water.

To nourish a growing global population, we’ll need to produce 56% more calories by 2050, while dealing with increasing climate-driven water risks like droughts and competition over resources. If we don’t manage water more sustainably, thirsty croplands could become a barrier to food security.

Our new tool, Aqueduct Food, maps current and future water risks to crop production using data from WRI’s Aqueduct platform and the International Food Policy Research Institute. This tool can help decision-makers map and proactively manage water threats to various crops and identify opportunities to improve food security.

Our new tool, Aqueduct Food, maps current and future water risks to crop production using data from WRI’s Aqueduct platform and the International Food Policy Research Institute. This tool can help decision-makers map and proactively manage water threats to various crops and identify opportunities to improve food security.

Using Aqueduct Food, we took a closer look at the picture of water and agriculture. These nine graphics illustrate why water is so critical for food security, and some of the solutions we can use to manage this important relationship.

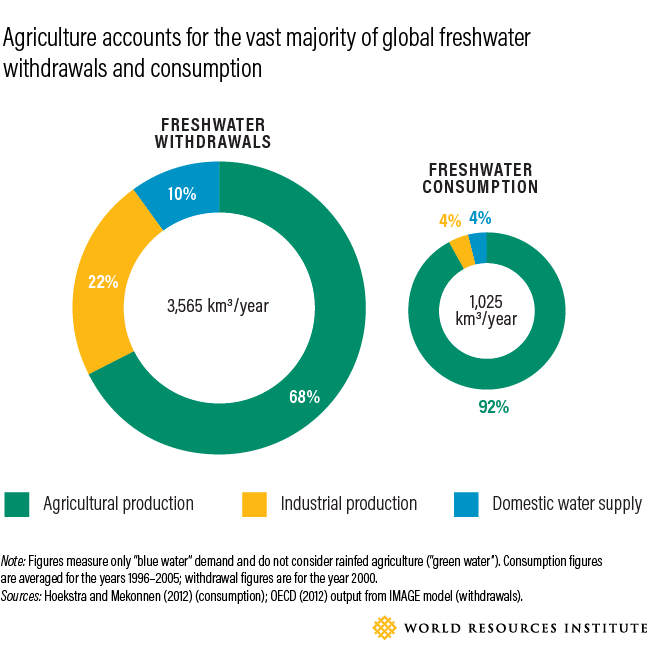

Agriculture Accounts for the Vast Majority of Freshwater Withdrawals and Consumption

Around 70% of the water that humans use goes to produce food, through crop irrigation and feeding livestock, among other uses. Our global appetite is increasing, driving up water demand. Households and industry are also adding to the demand for water, increasing global water stress (an indicator of competition over water). Humankind already uses twice as much water today as in 1960. Climate change makes satisfying this growing thirst more complicated as rainfall patterns shift, and hotter temperatures necessitate more water due to faster evaporation.

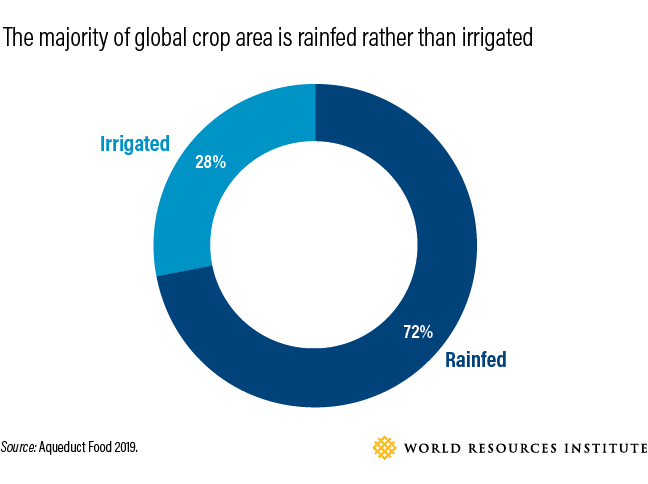

How Crops Are Grown Can Shape Their Impact on – and Vulnerability to – Water Security

Crops can be watered either by rain or irrigation. Irrigated crops draw from common water sources.

Nearly three-quarters of the world’s cropland is rainfed. Rainfed crops are particularly vulnerable to drought – which is being exacerbated by climate change in many parts of the world. Irrigated land may be better able to cope with unexpected or extreme weather, but as more water needs to be withdrawn from rivers and groundwater, there will be less available for other purposes.

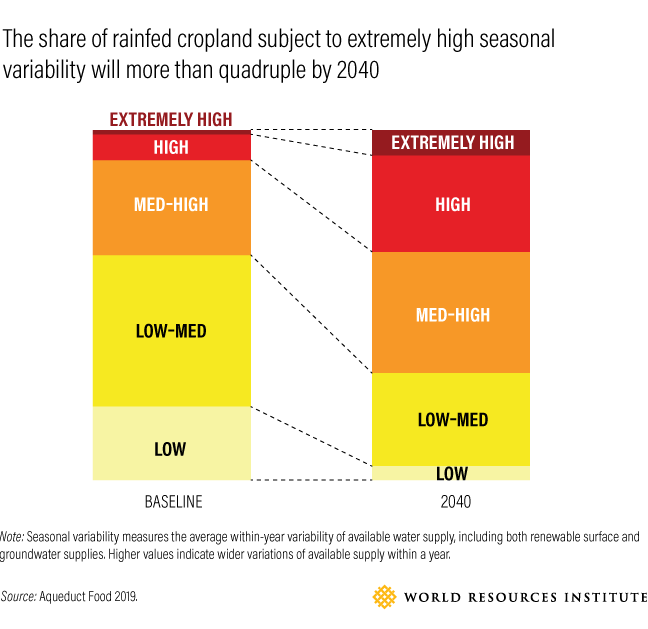

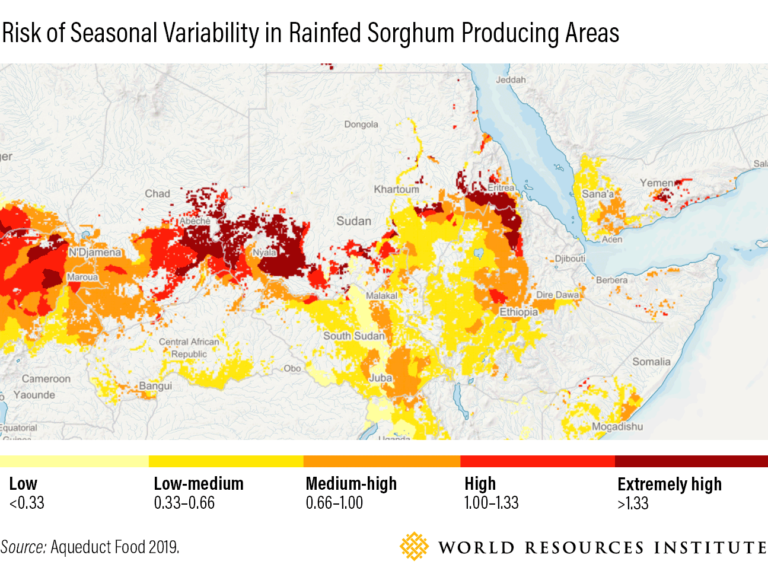

Rainfed Crops Are Vulnerable to Changes in Weather Patterns, Which Are Intensifying Due to Climate Change

Rainfed crops will feel the impacts of climate change the most. Farmers are used to the variability of rainfall within a year, seen in the wet and dry seasons. But seasonal variability of water supply will increase in many areas as the climate changes. Aqueduct Food’s data shows the amount of crop production in 2010 facing high and extremely high seasonal variability will more than quadruple by 2040 in a business-as-usual scenario.

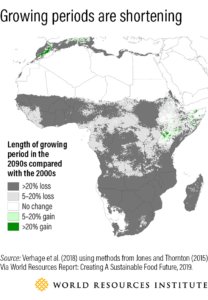

At the same time, growing seasons may become shorter in regions that are already vulnerable. As seen in the graph below, much of sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the largest share of the population at risk of hunger, is projected to experience a 20% reduction in the length of the growing period in 2090 compared to the 2000s. Climate change impacts like increased seasonal variability and warming temperatures disproportionally hurt poor communities reliant on rainfed agriculture. If the rains don’t come, they can’t farm.

Many areas in sub-Saharan Africa already face high seasonal variability of water supply. For example, in Eritrea, more than half the population is at risk of hunger. Sorghum is an important crop for food security, but two-thirds of sorghum production is grown in areas with high to extremely high seasonal variability.

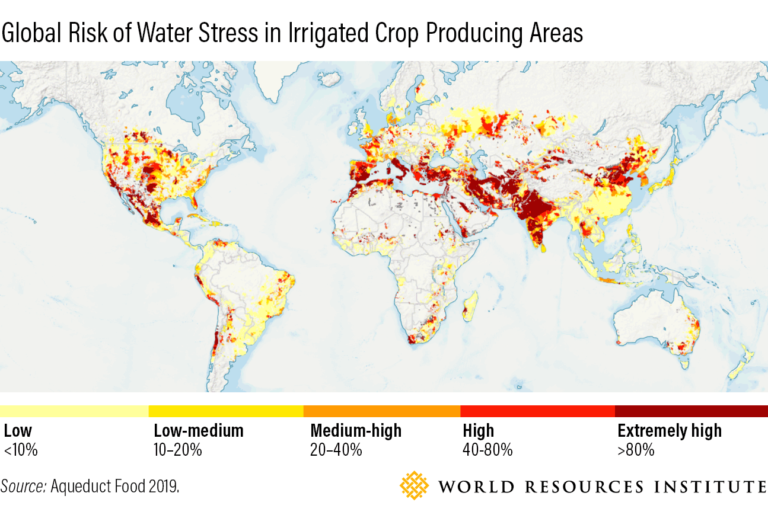

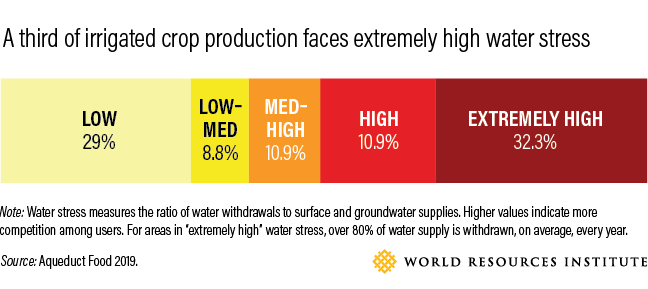

Irrigated Crops Contribute to and Suffer from Water Stress

Although irrigated agriculture only makes up about one-quarter of all cropland, it produces 40% of the world’s food supplies. Currently, about one-third of irrigated crops face extremely high water stress, meaning that water withdrawals are highly unsustainable. Water for irrigation usually comes from the same sources of water used for households and energy utilities. When water stress is high due to low supply, high demand or both, fierce competition over water can arise, especially if management is poor.

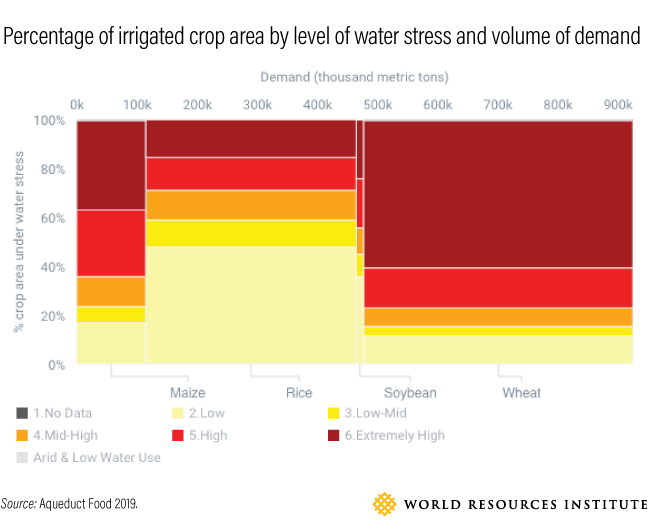

Wheat Is the Most Water-Stressed Major Commodity Crop

Of the four major globally traded crop commodities – maize, rice, soy and wheat – wheat is in the highest demand for household consumption and faces the highest threat from water shortages. More than half of irrigated wheat is exposed to extremely high water stress. By 2040, nearly three-quarters of wheat production will be under threat. Wheat is crucial for food security and economies in every corner of the globe.

Solutions to Advance Food and Water Security

There are many ways we can tackle these challenges. Here are two that anyone can help put in practice:

- Reduce food loss and waste: A quarter of all water used for agriculture grows food that is ultimately wasted. Cutting food loss and waste from farm to from — including in your own home — also means cutting water waste.

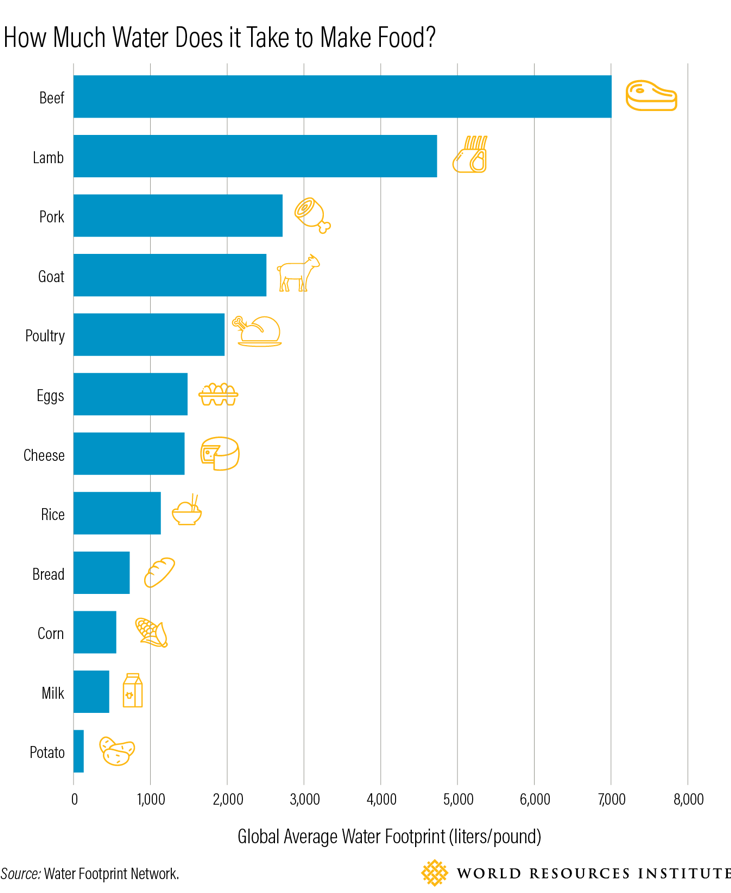

- Shift diets towards less water-intensive foods: The water footprint of beef is 7,000 liters per pound, 50 times greater than the water footprint of potatoes. By eating less water-intensive foods, we can reduce the amount of water required to feed a growing global population.

These are just some solutions to increase water and food security. Farmers can also implement best practices, such as rainwater harvesting. Governments can offer incentives to farmers to grow the right crops in the right places and utilize water-saving technologies like drip irrigation.

We won’t solve food insecurity without adequately addressing water insecurity.

Water and food are intrinsically linked. We won’t solve food insecurity without adequately addressing water insecurity.

About the authors: Sara Walker is a Senior Manager for Water Quality and Agriculture on WRI’s Water Program. Rutger Hofste is an associate for WRI’s water team. Leah Schleifer is a Research and Engagement Associate on WRI’s Water Program.