The UK Government just released a report that looks at the quality of different types of schools in Lagos Nigeria. The government wanted to know how our schools compare to others. It’s an important subject because international policy makers need to know how best to help children in such regions when it comes to education.

The report has a number of interesting and encouraging findings for non-state education providers, but there is one in particular that stands out to me.

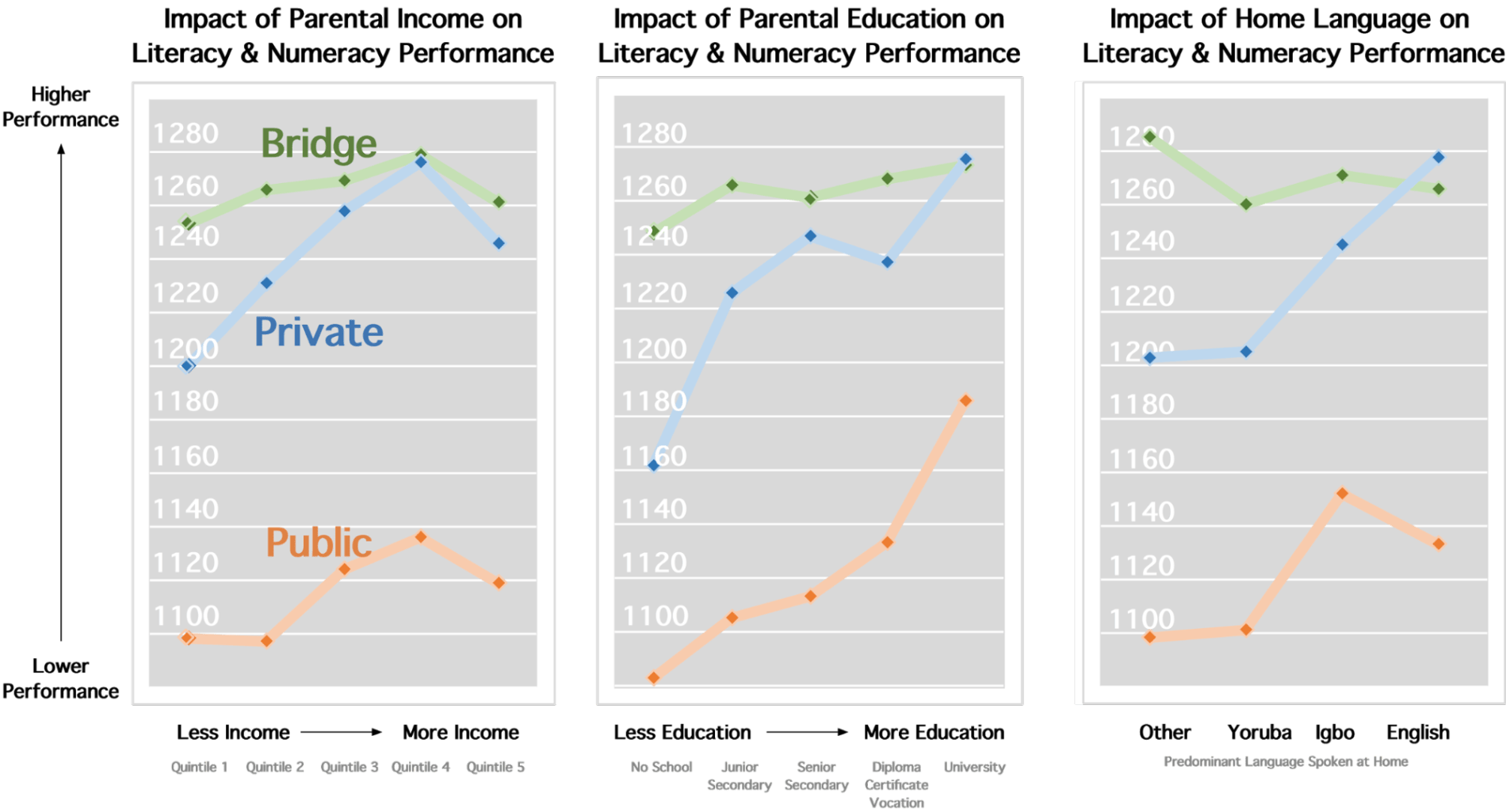

Parental income, parental education, and speaking English at home had no effect on Bridge students’ academic performance in Lagos, according to a DFID study.

Pause and think about that for a moment. No achievement gap. This contradicts decades of educational research, from Coleman’s landmark 1966 study of academic outcomes among US students to OECD’s 2016 global study of excellence and equity in education, asserting family background matters more, perhaps much more, than the differences between the schools students attend. The finding of equity in learning at Bridge is groundbreaking.

Photo Credit: Bridge International Academies – “Reversing Education Inequities in Lagos, Nigeria”

A recent survey of US Public Charter School studies suggests that some “no excuses” charter schools in urban areas have closed achievement gaps, but also recognizes these studies often fail to account for differences in parental motivation or peer effects, both of which are likely to influence student performance.

These surprising results come from a just-released DFID study of student learning in Lagos comparing three types of schools: public, low or mid-fee private, and low-fee Bridge International Academies. The presence of two types of fee-based schools strengthens the study tremendously, since both are likely to attract similarly motivated parents and, in turn, attract cohorts of peers with similar attributes. While these remain unmeasured characteristics, there are no strong reasons to expect systematic differences in parental motivation or peer characteristics between Bridge and other, similarly-priced private schools.

In these graphs, the slopes of each line tell an equity story; the flatter the line, the more equitable are performance outcomes across each family background characteristic. Looking at Bridge student performance, the green lines are relatively flat. Performance on literacy and numeracy assessments are quite similar irrespective of family income, education, or language state. This isn’t true of the other lines, especially for family education, which is a strong predictor of performance for both public and private school students (e.g., private schools in tulsa).

At Bridge, equity doesn’t come at the expense of performance. Bridge student performance is strong, whether the student’s family is among the poorest or least educated, no matter which language is spoken at home. In fact, Bridge students from the poorest and least educated families performed just as well as private school students from less poor and better educated families.

Photo Credit: Bridge International Academies – “Reversing Education Inequities in Lagos, Nigeria”

The research did not suggest why these patterns exist. When asked to explain the findings, Bridge leaders were quick to point out several features of Bridge’s model designed to produce more equitable outcomes. First, equity is a core Bridge value. “In 2008,” says co-founder Shannon May, “we set out to design a school that would strive to defy the heavy gravitational pull poverty has on boys and girls’ lives. A school is a place where social justice should be enacted every day, and made real through the increased confidence, skills, and opportunities that each child gains because she attended school. To achieve its purpose, a school must struggle to ensure that the income or education of a child’s parent is not what determines her future.”

To accomplish this, teachers are trained to better support struggling students. Four specific practices help teachers avoid their natural tendency to focus on the brightest and most engaged students. “These practices: cold calling, small group sessions, independent practice, and, check and respond directly with feedback,” said Nigeria Director Olu Babaloa, “ensure that all students are learning the material.” Bridge’s Chief Academic Officer, Sean Geraghty, also cited these practices and added that Bridge’s schedule, including a longer school day, lessons and materials tightly aligned to the national curriculum, and supplemental literacy and numeracy courses, allow “kids who may otherwise be behind more opportunities to ‘catch up’.”

The EDOREN study, funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), and conducted by researchers at Oxford Policy Management and the University of Sussex, was “designed to describe learning levels for public, private, and Bridge schools in Lagos and identify factors that may help account for differences in learning achievement.”

This study matters because of the outsized role played by private school providers in Lagos. Up to 75,000 children in Lagos do not attend school. In a country which has the most out-of-school children in the world, parents often lack nearby, quality schooling options. Government provision of schooling is inadequate and private schools have become a major service provider, even for poor families. An estimated 71% of families – in Lagos – at or below the poverty line send their children to private schools (Tooley & Yngstrom, 2014). When these schools achieve equitable outcomes, they allow the children of Lagos to pursue greater opportunities. Such opportunities ensure that these families’ financial sacrifice is not in vain.