How the U.S. Could Learn from the United Kingdom’s Parental Leave Policies

I recently spoke with Lucy (whose name has been changed for anonymity), a young woman expecting her first child, about what she planned to do in terms of returning to work after the baby was born. Lucy is a postdoctoral research fellow from the United Kingdom, and while I already knew she would return to her position, I wanted to know more about how she had planned out her maternity leave. Lucy prefaced nearly every statement with the acknowledgement that she indeed was extremely fortunate in having one of the more generous maternity leave policies offered in the United States through her University employer. However, Lucy’s husband must return to work so soon after their child’s birth that additional care-taking plans were made out of necessity. Lucy’s mother would fly in from the UK – timing her trip so that she arrives just as Lucy’s husband has to return to work.

Lucy will take a total of 12 weeks of maternity leave before she must return to work. She receives six weeks paid vacation, and prior to taking this time, she must exhaust all of her vacation and sick days for the year. She plans on taking an additional six weeks of time of unpaid leave under the Family Medical and Leave Act . Her husband, due to the fact that North Carolina law does not mandate paternity leave, will take a combination of paid and unpaid leave. Lucy and her husband are lucky in that they both have employers who are extremely understanding about their absences, and the financial stability to take unpaid time off. Most Americans, however, are nowhere near as fortunate.

Photo Credit: Flickr/Meagan

In stark contrast to United States’ policy are the parental leave policies of the United Kingdom. In the UK, where Lucy grew up, statutory mandatory leave is up to 52 weeks off, and employees can be paid statutory mandatory pay (SMP) for up to 37 weeks. This leave can be split amongst parents however they see fit, (although mothers must take the first two weeks after the child’s birth). Parents can stay home at the same time, or can take two shifts, thereby increasing the total time spent at home with the newborn. Furthermore, statutory mandatory leave does not need to be taken concurrently; a parent can use up to three blocks of leave during the first year after the child is born.

Finally, this leave is paid. SMP is broken down as follows: eligible employees receive 90% of their average weekly earnings (AWE) for the first six weeks. For the remaining time taken, they earn the lower of £139.58 or 90% of their AWE. Finally, should the baby arrive prematurely, your leave can start the day after the child’s birth (notice need only be provided with proof of delivery by a doctor or midwife); employees also qualify for leave in the event of a stillborn baby or if the baby dies shortly after being born.

Related articles: “MILLENNIALS AND THE NEW MODERN FAMILY”

“WHEN CHILDREN NEED US MOST, WE CAN DO BETTER”

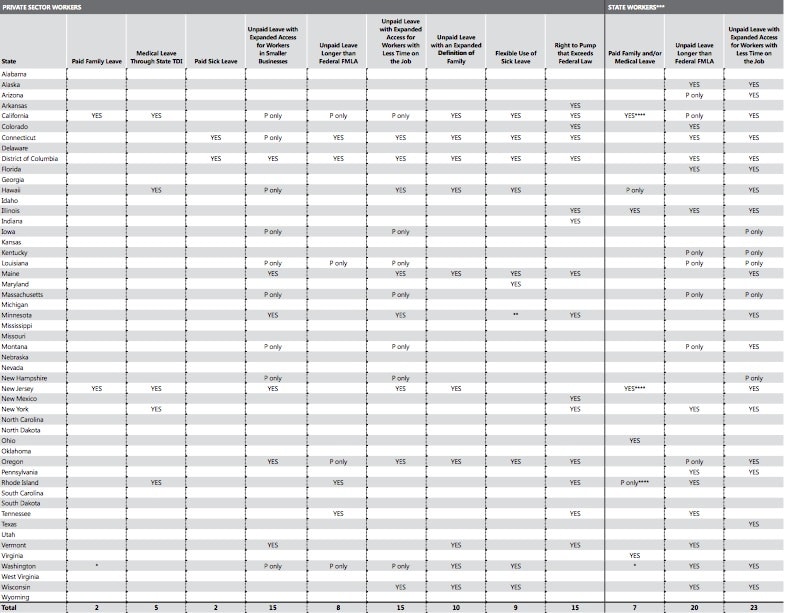

On the other hand, in the United States, the following chart demonstrates clearly that many states do not offer much more, if anything, than the federally mandated maternity leave under the FMLA – 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the birth or adoption of a child. In many states, there is no mandated paternity leave at all, so if employees are lucky they can cobble together an amalgam of vacation days and personal days so as to spend as much time at home with their new babies. The facts are that it is nearly impossible to take paternity leave in the U.S., and that there is a severe societal pressure on men to take little to no leave (a friend and I recently laughed in disbelief at her husband’s employer’s 1-day paternal leave policy). This has a severe effect on women in the workplace, who endure a much more physical ordeal and typically must take some time to recover, thereby disadvantaging them in the eyes of employers.

In the Photo: State by State Comparison of Select Policies. Credit: National Partnership for Women and Families

Recently, as more women with careers have become pregnant, the disparity of the effect on their career trajectory versus that of the career trajectory of their male partners has become painfully obvious. Moreover, many partners who are not carrying would love to have the opportunity to spend more time with their child following birth! They would happily take more time for paid paternity leave, if it was offered and if taking paternity leave did not seem so taboo in today’s corporate culture. For proof, one need look no further than the well-deserved adulation that Mark Zuckerberg has received in the press for taking a hands-on role in parenting his daughter (Zuckerberg took two months of paternity leave from Facebook, and offers his employees four months off. A number of articles laud Zuckerberg as making it all right for young fathers (and members of same-sex couples) to choose to spend time with their new families without sacrificing career opportunity; however, the government ought to mandate similar policy.

It is not simply that women are disadvantaged in the workplace by the unequal burden placed on their shoulders when it comes to childrearing in our society. Fathers and children both also benefit from paid leave. An article published in May of 2012 in the National Partnership for Women & Families summarized several studies succinctly with the following:

When fathers take leave after a child’s birth, they are more likely to be involved over the long term in the direct care of their children. One longitudinal study of U.S. families shows that fathers who took two or more weeks off after the birth of their children were involved in the direct care of their children nine months longer than fathers who took no leave. Access to paid family leave encourages fathers to take leave. In California, as the state’s family leave insurance program has become better established, fathers have become more likely to take paid family leave.

—National Partnership for Women & Families, Report: Expecting Better

In order to improve support of parents in the United States, we need to expand upon services provided in Great Britain, France and Canada. The United States should adopt an initiative similar to the one previously discussed in the United Kingdom, where new parents (adoptive or biological) are granted a substantial amount of parental leave (52 weeks) to split among themselves as they see fit. This would enable parents to take into account the specific and individualized nature of each family unit so as to most effectively support their own circumstances and household.

While I believe that the United States certainly ought to consider simply adopting the UK’s 52-week leave policy, even a 24-week policy with 12 weeks paid would significantly improve conditions for new parents. Furthermore, the US needs to create a mandatory paternity leave of 4 weeks. In this fashion, we can remove the impetus to force men to forgo spending time with their newborns in order to fulfill their traditional roles as provider for the family in the workplace, and to force women to bear the brunt of child-rearing by default.

While such programs are certainly expensive for the state, there are plenty of options for funding. In a March 2015 article published in Forbes, Aparna Mathur proposed funding paid maternity leave in two ways: first, by making the Child and Dependent Care tax credit refundable, and second, by allowing families to access these benefits anytime during the year (Mathur explains that women need to access these benefits at a specific time, which would not necessarily coincide with the receipt of a tax refund). Alternatively, the government could mandate through taxes that private corporations subsidize such programs.

Regardless, we must discuss how to fund such legislation and then implement it. Currently, the United States’ policies significantly penalize poor mothers, particularly single mothers. Discussed in greater detail in Pacific Standard, Maya Dusenbery sheds much-needed light on how a lack of paid maternity leave compounds the issues that face low-income mothers, many of who sacrifice their own health to return to their jobs as quickly as physically possible. Too many low-income mothers return to work each year before they are actually physically able.

Dusenbery references startling statistics. A survey that found that “80 percent of college graduates took at least six weeks off, while only 54 percent of those without college degrees did so.” Exemptions that ensure that “less than a fifth of all new mothers are actually covered by FMLA . . . disproportionately affect low-income workers, who are more likely to work for small businesses, change employers frequently, and piece together multiple part-time jobs.” And finally, another survey “of women who had a baby in 2005, [which found that] more than half of the respondents reported that they didn’t stay home as long as they would have liked and, of those women, more than 80 percent said they lacked the financial resources to do so.”

Clearly, neither mothers nor fathers, adoptive or biological, feel able to take the parental leave they desire to spend with their families at a crucial and demanding time. It is time to reform the United States’ policies, so that we can enable parents of all socioeconomic classes to tread water during this vital time.