Different forms of discrimination and marginalization — such as racism, ableism, and discrimination on the basis of gender identity — overlap and interact to give some people an advantage while disadvantaging others, thereby creating intersecting systems of inequity.

Building on decades of Black feminist theory and activism, the term “intersectionality” was first coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. The concept also resonated with some Indigenous scholars and Knowledge Holders.

It is more important than ever to confront the powerful intersecting systems of inequity in our societies to effectively reduce climate vulnerabilities. The World Meteorological Organization reported in November 2025 that the past 11 years have been the warmest in 176 years and that extreme weather events cause “massive social and economic disruption.”

Globally, discrimination remains widespread and has been rising since 2015, disproportionately affecting certain groups, according to the United Nations. Anti-LGBTQ+ policies and legislation and the weakening of legal protections against gender-based violence are just two of the concerning signals of regression that threaten efforts to secure human rights for all.

At the same time, over the past decade, the global emphasis on equity and justice in climate action has grown across various spheres of influence, including academic, policy, and civil society arenas.

As the global community works to close the adaptation finance gap and moves from adaptation planning to implementation, there is an opportunity to ensure that adaptation efforts reach the most vulnerable. But first, we need to deepen our understanding of the connection between systems of inequity and vulnerability to climate change impacts.

What systems create inequity in societies?

Various forms of discrimination exist in societies, rooted in histories of domination that assign people differential value according to race, ability, caste, class, sexual orientation, gender identity and/or expression, and sex characteristics.

Any form of discrimination disadvantages some people while benefiting others, leading to injustice and an unfair distribution of resources, services, opportunities, and human rights —this is how inequities are created.

We deliberately refer to “systems” of inequity to emphasize that discrimination is structural, extending beyond people’s attitudes and stereotypes to include deeply entrenched institutional practices. Systems of inequity are therefore embedded in and reproduced by societies through laws, policies, institutions, and social norms. Some common systems of inequity include racism or discrimination based on race or ethnicity; patriarchy, where discrimination is based on gender; or ableism, which entails discrimination against people with disabilities.

People’s identities have multiple overlapping factors, which means they experience intersecting systems of inequity that interact in unique ways. The importance of the systems of inequity is dynamic and varies by context — for example, old age can generate respect or discrimination and marginalization, depending on the situation.

How do intersecting systems of inequity connect with vulnerability to climate change?

People around the world are already negatively impacted by more frequent and intense climate hazards, such as floods, droughts, and rising temperatures due to climate change. These impacts are expected to intensify in the future.

Some people face disproportionate impacts from climate hazards stemming from greater exposure in some cases — for instance, riverbank residents encounter greater flood risk than those further inland — or from greater vulnerability, which is the focus of this article. Greater vulnerability increases the likelihood of severe negative effects from climate hazards, resulting in greater risk for certain groups.

There is solid evidence that inequities contribute to vulnerability and that high levels of inequity make societies less resilient to climate change. However, the relationship between intersecting systems of inequity and the conditions that increase people’s vulnerability to climate change is often overlooked or oversimplified. This can result in unhelpful generalizations about who is most vulnerable to climate risks, potentially leaving some groups out and resulting in ineffective solutions — or worse, actions that exacerbate or create new vulnerability.

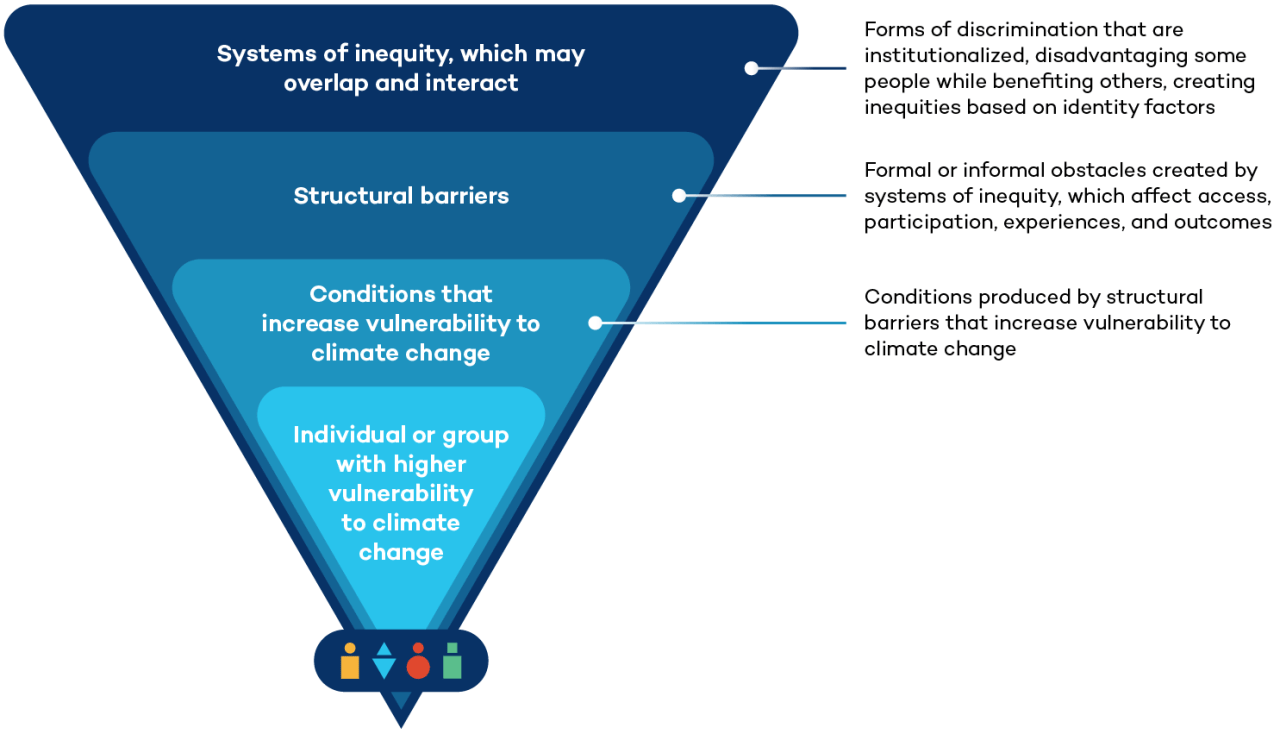

Figure 1 helps us visualize the linkages between intersecting systems of inequity and vulnerability to climate change.

Systems of inequity. The top layer of the pyramid illustrates the broader intersecting systems of inequity in society. As noted earlier, these systems are forms of discrimination that are normalized and legitimized through institutions, laws, policies, and social norms. They marginalize and disadvantage some people while benefiting others, creating inequities. As noted above, examples of systems of inequity include racism, ableism, and patriarchy.

Structural barriers. The intersecting systems of inequity faced by individuals or groups often translate into structural barriers. These are formal and informal obstacles that affect access, participation, experiences, and outcomes. The obstacles are created by, for example, discriminatory laws and policies, exclusionary social norms, and inequitable resource flows. These structural barriers reduce people’s access to — and benefits from — resources, services, and opportunities, and impinge on their human rights. These are represented in the second layer of the pyramid.

Conditions that increase vulnerability to climate change. The third layer represents the conditions that are created by structural barriers, which directly affect individuals or groups vulnerable to climate change. This includes conditions such as poverty, being unhoused, lacking access to services, or social isolation.

Figure 1. Linking intersecting systems of inequity with climate vulnerability

The figure shows how different systems of inequity create structural barriers that lead to conditions that increase vulnerability to climate change for individuals and groups. Effective adaptation actions need to acknowledge and address these barriers and conditions — and the systems that create them — to achieve equitable outcomes. What the diagram does not show is how the systems of inequity may overlap and interact, reinforcing or adding additional structural barriers and further exacerbating vulnerability to climate change.

How does this manifest in people’s everyday lives?

To illustrate these linkages with a fictional example, imagine Sabitri, an older woman with a mobility-related impairment living in a mountainous rural area that is experiencing increasingly frequent and severe floods and droughts due to climate change.

Systems of inequity. In Sabitri’s context, she experiences a unique combination of gender-based discrimination, ableism, and ageism.

Structural barriers. For Sabitri, social norms related to gender and age have led to exclusion from community decision making and public life. Though policies are in place that promote equal employment opportunities and access to services for people with disabilities, in reality, most public spaces are not accessible to people with a mobility impairment, and the health services in her community are under-resourced and not equipped to address her complex needs.

Conditions that increase vulnerability to climate change. Sabitri’s social isolation means she is less able to access climate information, which in her community is primarily distributed at community meetings hosted by the local office of the meteorological agency. Her access to services is further restricted because her disability is not accommodated for, which increases her vulnerability during heat waves and other extreme events. During floods and wildfires, the evacuation centres established by the government are not accessible to someone with a physical disability. Since her income-generating opportunities have been constrained by exclusion from the labour market for people with mobility impairments, she lacks savings, limiting her options to manage climate risks. Finally, her ability to influence local authorities to provide better services is constrained by her marginalization in community decision making.

Individuals or groups with higher vulnerability to climate change. As a result, Sabitri, along with other older women with disabilities in her community, is considerably more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than her family members and neighbours. Addressing these compounding factors is essential to ensure she is not left behind as her community adapts to climate change impacts.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

Why is an intersectional approach central to understanding vulnerability to climate change?

Understanding vulnerability is essential for effective adaptation to climate change. Inequities are not the only root cause of climate vulnerability, but they are one of the most significant drivers, alongside weak governance and ecosystem degradation.

An intersectional approach enhances our capacity to address intersecting systems of inequity that undermine resilience for individuals, communities, and society. It transcends single-issue analyses — such as those addressing gender or age in isolation — and inclusion efforts that simply compare climate vulnerabilities across social groups, assuming they are homogeneous.

It shifts attention from individual experiences to the systems that create and sustain discrimination, making some people far more vulnerable than others.

This approach recognizes that the people who are most at risk from climate change are often those who experience multiple, overlapping forms of discrimination. By understanding how intersecting systems of inequity relate to vulnerability, we can identify climate change adaptation actions that challenge or prevent the reinforcement of systems of inequity.

Climate risk assessments provide a strong starting point for adopting an intersectional approach. Revealing how overlapping systems of inequity heighten vulnerability to climate change enables more targeted allocation of adaptation resources. This, in turn, can yield broader benefits by advancing human rights and fostering more just societies.

** **

This article was originally published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and is republished here as part of an editorial collaboration with the IISD. It was produced by IISD as part of the Understanding Climate Risks Through an Intersectional Approach (iCRA) project. The iCRA project is implemented by the International Institute for Sustainable Development; Prakriti Resources Centre, Tewa – Women’s Fund of Nepal, and Community Development & Advocacy Forum Nepal in Nepal; and Urban Earth, Triangle Project, and the Western Cape Association of and for Persons with Disabilities in South Africa. IISD is grateful to the partners and to Ashlee Christoffersen, Anne Hammill, Bimal Regmi, and Katharine Vincent for their review and inputs on this article. This work was funded by UK aid from the UK government and by the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada, as part of the Climate Adaptation and Resilience (CLARE) research program. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the UK government, IDRC or its Board of Governors.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: IISD.