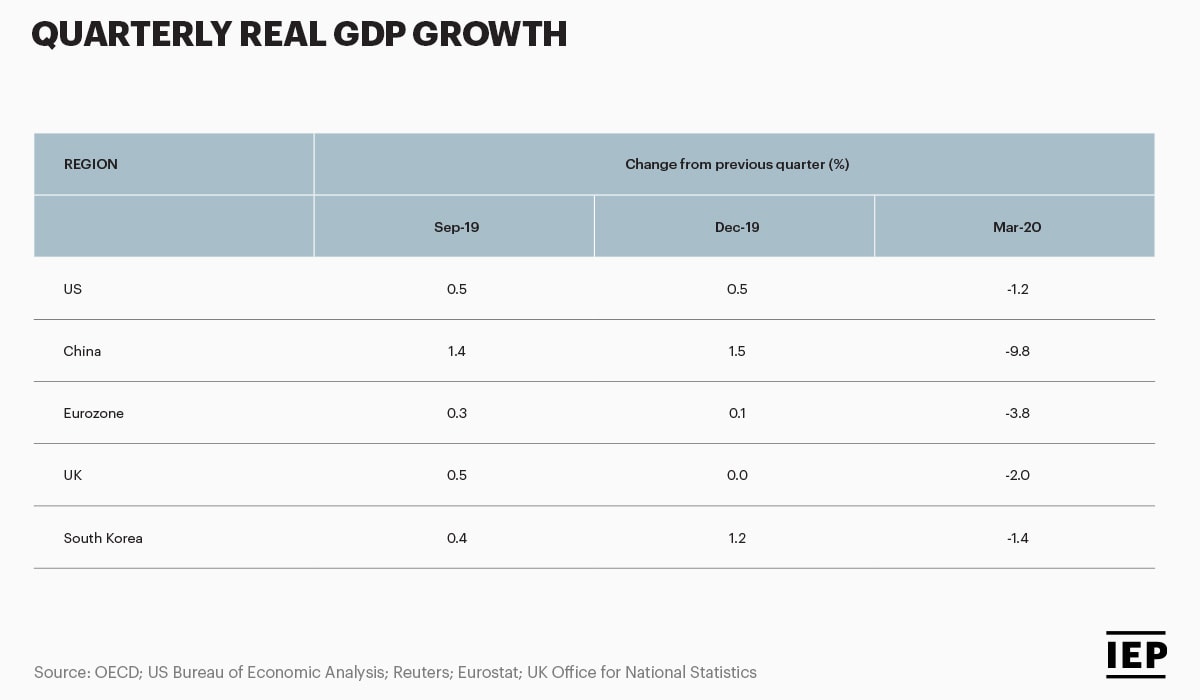

The COVID-19 and Peace report by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) presents a detailed look on the economic ramifications of Covid-19. According to the report, the US GDP fell 1.2% from the prior year in the first quarter of 2020 – an annualized decline of 4.8%. The euro area experienced a significant decline of 3.8%, while China’s production decreased by 9.8%, which is equal to an annual rate decrease of 34%.

When it became obvious that the contagion would not be constrained to East Asia in February 2020, global financial markets were severely affected by the COVID-19 crisis as evidenced by the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) World stock index decreasing by 34%. The global stock markets have recovered after March, but there are expected to be more downswings. The extent of this epidemic and economic instability may have been misinterpreted by the financial markets. Furthermore, the increased funds for more investment have been the result of the stimulus programs and lowered interest rates. The emergence of different tendencies among corporate and government bonds was a reaction to the uncertainties brought about by the crisis. Since the private sector was confronting more risks there was a swift increase in yields while long-term government bonds saw a decrease in yields along with their prices rising.

The Outlook for the Global Economy

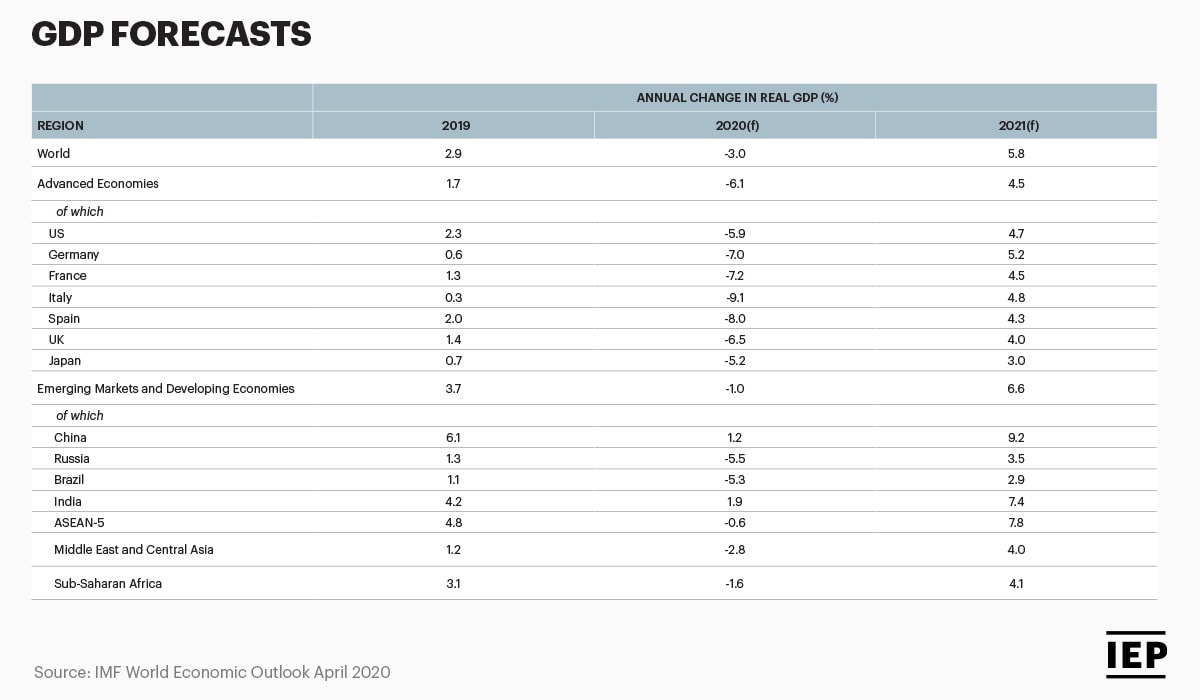

Several organizations released projections and estimates to help stakeholders gain insight into the severity of the economic recession. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects rapid economic decline of 3% for the world economy in 2020 and recovery in 2021. The expected decline is serious for North America and Europe’s main developed economies along with China and India projecting to not contract. These forecasts are being made under the assumption that the pandemic will be contained, rapidly overcoming trade conflicts and the rising availability of capital to ease the global crisis.

Related articles: Covid-19 and Peace: examining the impact | The COVID-19 Pandemic and Socio-Economic Development | How black markets have adapted to COVID-19 | The COVID-19 Pandemic and the impact on violence

More countries are likely to reduce their peacekeeping commitments as their economies contract. Reduced international aid will also negatively impact countries who are heavily reliant on it such as Liberia, Afghanistan, Burundi and South Sudan that are vulnerable and experiencing conflicts. Most nations would have trouble funding costly initiatives like in Syria or in Iran, assisting militias like Hezbollah for neighboring Yemen, Turkish and Russian assistance.

The combined decline in finance, transport and businesses contributed to a decrease in global oil prices. These markets were already adversely affected by an inadequate supply from Russia and Saudi Arabia, which were unable to find consensus on output restrictions. For the first time in memory, on 20 April, the crude oil price became negative. The market crashed so quickly that purchasers were being paid to clear surplus inventory by the overstocked suppliers. Thanks to the manner in which potential contracts are written, the negative price was short-lived, and oil prices quickly returned to positive territory. The extraordinary event nonetheless reflected a worldwide deterioration in demand.

This dramatic drop in oil prices will have an impact on the Middle East political regimes, especially Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran, and may contribute to the collapse of the U.S. shale oil industry unless oil prices rebound to their previous levels. The national security and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela have been aggravated by the pandemic and poor oil markets. This has also contributed to the adoption of strict border controls in Colombia, Brazil and other countries with regard to Venezuela which has resulted in additional difficulties for Venezuelans.

Central banks, in an attempt to alleviate the economic effects of this pandemic, cut down funding to the banking sector in hopes of reducing the debt repayment costs for businesses and families. Nevertheless, relatively low levels of interest until COVID-19 would ensure that cuts in levels will not offer global economies enough stimulus. Countries like Brazil, Argentina, Pakistan and Venezuela might not have the ability to get a sufficient amount of loans to help their economies rebound which may result in more unrest, instability and violence.

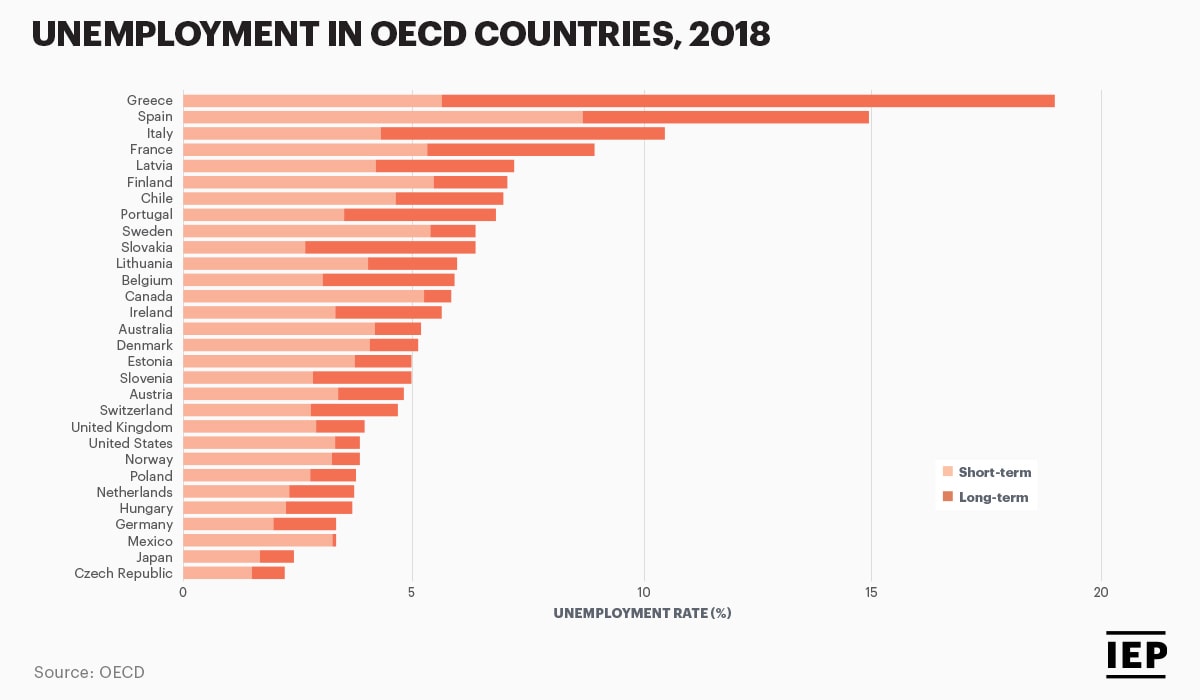

The pandemic has caused chaos on labor markets. As a consequence of business sector shutdowns and social isolation, unemployment levels have grown dramatically worldwide. The number of US citizens jobless early in the year rose to nearly 200,000 a week. At the end of March, this figure had risen to 6,867,000. Consequently, many nations are also expecting a rise in unemployment. Countries with high unemployment until the pandemic will experience a downturn in their economies, as unemployment would rise in a moment of vulnerability. Countries with low degrees of long- or short-term unemployment, by comparison, might find absorbing the effects of this pandemic and reassigning their workforce afterwards to vital industries easier.

Looking to the Future

One of the big consequences of the global crisis has been the demonstration of how the world relies on China for the supply chain of many goods. Japan and India are paying businesses to shift production away from the PRC. Chip manufacturers, such as Intel, have committed themselves to the construction of more factories in the United States. China’s failure in production during the pandemic quarantine has shown the dangers of overreliance on single manufacturing points. Its Asian neighbors will be the main beneficiaries of the production shift away from the PRC, however this process can take years or even decades to happen as it takes time to switch supply chains.

As the economic situation worsens, it will be harder for countries to repay their current debt. The combination of debt and weak activities is likely to increase poverty, political instability and violence. One of the prime examples is food security, which will be affected in countries such as Burundi, Yemen and Venezuela who will be experiencing increasing food shortages. Even before the Covid-19 crisis, a total of 113 million people were already on the edge of starving in 53 countries. The pandemic has encouraged governments, companies and individuals to look for ways of improving the capacity of medicinal care, mitigating the economic impact of isolation, and helping vulnerable sections of society but only time will tell whether it will be enough.