The mass adoption of cryptocurrencies could lead to an escalating climate crisis if things were to remain as they are. Cryptocurrencies are currently disproportionately affecting those most vulnerable and exacerbating social and environmental challenges for those already experiencing multiple dimensions of deprivation, new research finds. Engaging in conversation about its impact and solutions are of utmost importance to mitigate its impact and make the industry more sustainable.

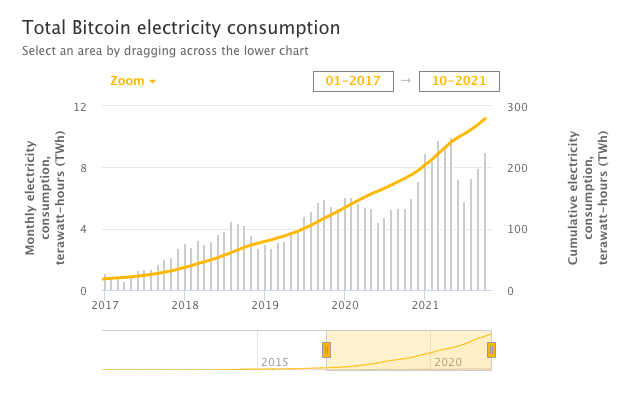

The digital infrastructure behind Bitcoin, the most popular cryptocurrency, requires as much energy as the whole of Thailand, with the majority of the energy generated from fossil fuels. Its carbon footprint – now exceeding the gold mining industry – is at an all time-high. Bitcoin emits approximately 90 Megatonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year, up from around 22 Megatonnes of CO2 annually just two years ago.

To put into greater perspective, one single Bitcoin transaction is equivalent to the total energy consumed by a US household for two months.

A new research paper by Peter Howson, from Northumbria University, and Alex de Vries from Digiconomist, the rise of cryptocurrencies could disproportionately impact those most vulnerable to the climate crisis.

It looks at the “disproportionate impact that those activities [cryptocurrency mining] are having on the world’s poorest rather than those who are participating in the sort of Bitcoin speculation mainly in the Global North.”

Prior to delineating why Bitcoin puts vulnerable communities at risk, it is important to understand how it works, and why it is unsustainable by design.

The unsustainable design of Bitcoin “mining”

Bitcoin is unsustainable by design. To create new Bitcoins, a process called “mining” is required, using a process known as Proof of Work (PoW) consensus protocol which is a huge contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. The mining process requires immeasurable computing power and a lot of energy for the blockchain to exist.

When a person invests in Bitcoin, the details of the investment are entered on a virtual ledger, called the blockchain. But the process is complete only when a “miner” verifies the transaction is legitimate. At that point, the transaction is locked into the blockchain, and the investment is finalised.

The verification process, which uses a PoW model, is energy-inefficient since it requires “miners” to race against time with each other to solve a cryptographic puzzle. They use trial and error to rapidly generate random numbers checking each one to test if it is the solution. The miner who solves the problem first gets a fraction of the transaction fee.

Finding the solution to the puzzle is not simple, and “winning” is a bit like a lottery. The more computer power one has, the higher the chances they may have of winning. Thus, in order to make Bitcoin mining profitable, a lot of highly specialised computers and short-lived hardware are needed to run 24/7 consistently looking for solutions to mathematical puzzles.

This Bitcoin mining business inevitably uses vast amounts of energy. It also has greater environmental and social impact as it leads to water waste (used to cool down the machines), and e-waste which is hazardous and mostly disposed of in developing countries.

How does Bitcoin mining exacerbate vulnerable communities?

The paper argues that “the unsustainable trajectory of some cryptocurrencies disproportionately impacts poor people and vulnerable communities where cryptocurrency producers [also known as miners] and other actors take advantage of economic instabilities, weak regulations, and access to cheap energy, and other resources” for greater profitability.

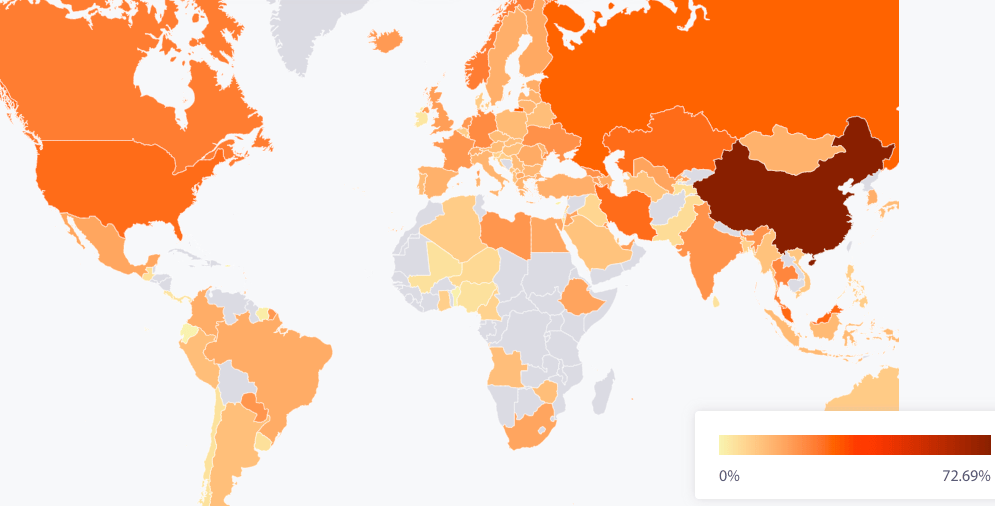

The Great Mining Migration is the latest and perhaps greatest example of this phenomenon – looking for the most profitable places to “mine” bitcoin – that began almost as soon as cryptocurrencies were invented. And at first, China was the most attentive and attractive host, making electricity inexpensive.

Until recently, nearly three-quarters of Bitcoin mining took place in China, and was concentrated in the provinces of Xinjiang, Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, and Yunnan where energy is cheap and abundant.

Since last year, President Xi Jinping’s stance on Bitcoin and cryptocurrency hardened due to rising financial and environmental concerns, fuelling a nationwide crackdown on the industry earlier this year.

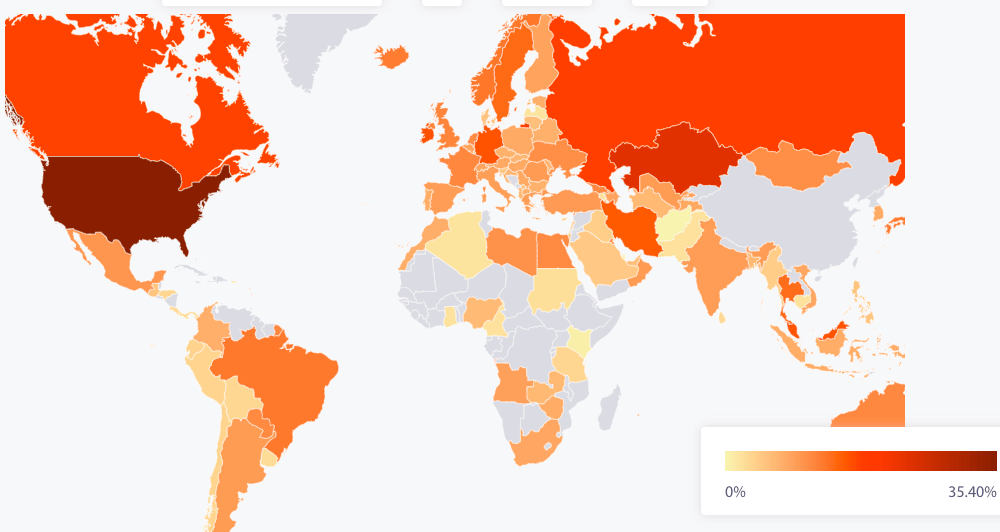

In order for mining operations to continue, many were forced to relocate. Taking advantage of the politically less-stable countries, with weak regulations and an abundant access to cheap, abundant, and dirty energy. Kazakhstan, and Russia have seen an immense increase in mining operations, as well as Canada and the US for their weak regulations.

A closer look into this mass exodus can be observed when comparing two maps from Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index. In the first map (February 2020), China represented 72.98% of total mining (or ‘hash’) rate. In the second map (August 2021) we can observe the drastic movement in mining operations moving completely away from China into the aforementioned countries.

This is worrying since only 1% of Kazakhstan’s energy mix is renewables, or, take the case of Canada where the company Black Rock Petroleum has agreed to host up to 1 million Bitcoin-mining machines relocated from China, which will be powered directly from natural gas.

The Great Mining Migration shows that mining operations will move according to the price of energy. As of 2019, only 23.2% of total global electricity was generated from renewable energy. Whilst the price of solar has drastically decreased, burning fossil fuel remains the main source of energy, and the cheapest for developing countries.

Mining operations thus relocate in developing countries leading to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions. This impedes developing countries from achieving their Nationally Determined Contributions goals, as well as adversely affecting those communities already vulnerable to the effects of global warming.

Several mining operations have sought to be “cleaner” relocating to the Democratic Republic of Congo where access to renewable energy is relatively cheap. Yet, this has come at the expense of local people being able to take advantage of their renewable energy for domestic usage, impacting their opportunity for a more sustainable future.

One research indicates that in 2018, for every $1 of Bitcoin value created, $0.49 had to be spent on mitigating health and climate damages.

What are the solutions?

Several countries have already implemented restrictions on Bitcoin. For example, Egypt, Morocco, and Bolivia have made it illegal to hold any cryptocurrencies.

Norway is looking to follow Sweden and implement a national crackdown on activities such as Bitcoin mining. They believe the amount of renewable energy Bitcoin mining is using in their country is unjustified at the moment, and that the EU should implement an EU-wide Bitcoin mining ban.

“Although crypto mining and its underlying technology might represent some possible benefits in the long run, it is difficult to justify its extensive use of renewable energy today”

– Norwegian local government and regional development minister Bjørn Arild Gram

Yet, as previously explained, national crackdowns do not impede mining operations from relocating and continuing their activity. What we need is a global coordinated plan to ban Proof of Work cryptocurrencies, and to incite all blockchains to be powered by the Proof of Stake (PoS) model.

What change would that make?

The Proof of Stake model: Why it would save energy

PoS is more sustainable as it attributes mining power to the proportion of coins held by a miner not bound to the number of computations. There would be no need to waste energy on solving complex mathematical puzzles. Instead, the “winner” is the one with the highest “stake”, i.e. putting forward the highest number of coins as “pledges”, and then getting rewarded.

The problem with this approach is obvious: The risk is rewarding the better off miners and creating income inequality among the cryptocurrency mining community. Yet the advantages are enormous and it has been estimated that PoS could cut energy consumption by 99%.

The shift away from PoW towards PoS is possible and has been a part of the Ethereum (second most popular cryptocurrency) blockchain since its conception.

But in order for the shift to work, the ban on PoW must be global.

You need to stop conflating cryptocurrencies and the proof-of-work algorithm. Not every cryptocurrency is running on a wasteful design. Innovation in the financial space is possible without exacerbating climate change and exploiting vulnerable communities: https://t.co/cSDXaDcJPL https://t.co/DrmfgEGON5

— Digiconomist (@DigiEconomist) November 17, 2021

Understanding how Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies still using PoW model, may cause great harm remains complicated, but we must continue to monitor their impact on energy sources and search for appropriate solutions to mitigate – or even reverse – the known adverse effects on the climate and on vulnerable people. That is if we are ever to establish bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as credible currencies based on a sustainable production model. Of course, this still leaves unanswered questions of ethics (cryptocurrencies are famously the currency of choice for illegal activities) and the issue of whether a cryptocurrency should be within the mandate of a country’s national bank.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: All Crypto coins placed on black surface. Featured Photo Credit: Executium.