Carbon pricing has had broad business support for over a decade. As a market-based mechanism, this is often the private sector’s preferred approach in addressing climate change. Consequently, carbon pricing is a convenient mechanism to measure trade association support for climate change. Support for this mechanism is not a sufficient commitment to climate action alone, and any support that is tied to displacing other tools essential to necessary emissions reductions should be rejected as being inconsistent with support for solving the climate crisis. Still, carbon pricing can be a foundational first step for businesses and the trade associations that represent them.

U.S. trade associations have historically served as a roadblock for climate policy. However, over the past several months, organizations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Business Roundtable, American Petroleum Institute and others showcased their evolving public positions on carbon pricing. As corporate voices strive to keep up with an administration dedicated to ambitious and immediate climate action across all of government, this shift in positions provides an opportunity to harness the political influence of trade associations to drive ambition in the corporate world. However, for improved public positions to have real meaning, trade associations must put their political and financial muscle behind these statements. Otherwise, their actions could be read as posturing to get a seat at the negotiating table to delay or even derail the administration’s climate plans.

Here is the current state-of-play:

1. What are trade associations saying about a carbon price?

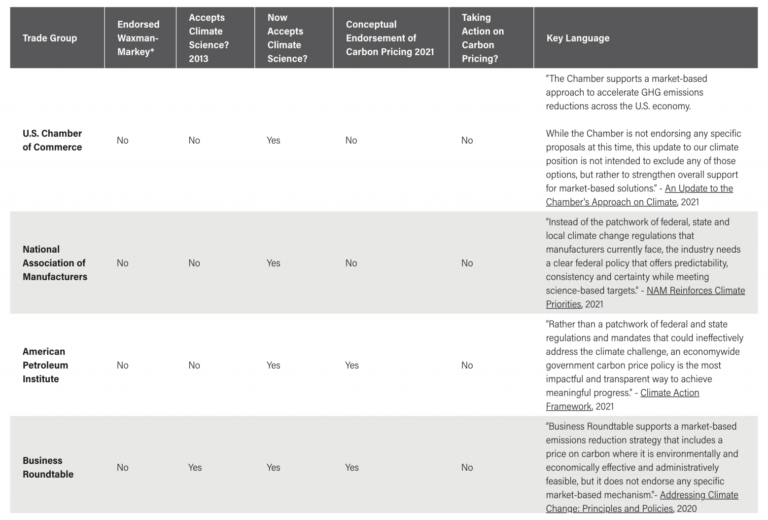

While U.S. trade associations are not homogenous, those that have members in heavy-emitting sectors — including groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers — have generally demonstrated a longstanding opposition to science-based climate policy. This extends to opposition toward carbon pricing, as represented by the Waxman-Markey Bill (American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009). The Waxman-Markey Bill was legislation to establish a cap-and-trade system for greenhouse gases that passed the House in 2009, but failed in the Senate. Despite critical business support from Fortune 500 energy and manufacturing companies, as well as hundreds of small businesses, many trade associations opposed the legislation.

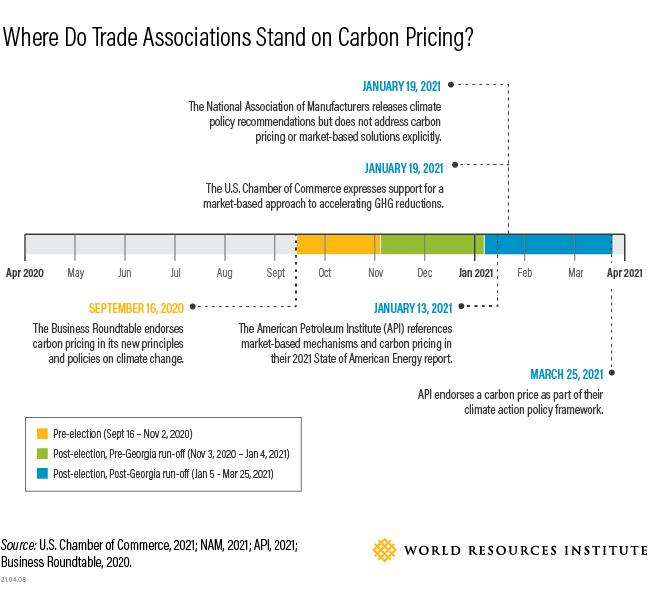

Recently, some of these same associations made headlines documenting a new openness toward carbon pricing. While these new policy positions vary in length and specificity, they have in common similar timing and no clear plan for follow through.

*The Waxman-Markey Bill (American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009) was legislation to establish a cap-and-trade system for greenhouse gases.

The Business Roundtable (BRT), a sector-diverse coalition of CEOs, moved first. The group made waves in September 2020 with the public rollout of its principles and policies for addressing climate change. While these principles are not groundbreaking, they represent a good understanding of the policy portfolio needed to address climate change, explicitly endorse a price on carbon and break away from oppositional climate positioning that was common before the results of the 2020 election. This is a notable departure from BRT’s reported neutrality on the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade proposal and its 2007 stance on climate change, which acknowledged carbon pricing but noted that membership was divided on mandatory mechanisms.

Following public pressure to align with BRT’s new positioning, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (“Chamber”) updated its own stance a few months later. The Chamber is a politically powerful trade association, which outright opposed the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill and continued to spend money in recent years on ads that discouraged climate policy. However, in January 2021, the Chamber updated its position on climate change to include support for market-based approaches to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The statement is notably vague, and though the Chamber provided no evidence that this position would translate into support for carbon pricing specifically, a tax on CO2 could theoretically fall under the “market-based” umbrella.

These shifts across broad business coalitions are also reflected in some sector-specific associations that previously obstructed climate policy. The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), another trade association that aggressively opposed the Waxman-Markey carbon pricing bill, is also one of the trade associations InfluenceMap found to be most opposed to progress on climate policy, alongside the Chamber. In 2021, NAM released a set of climate policy recommendations on the same day the Chamber updated its position. These recommendations leave much to be desired in terms of ambition and include concerning language around displacing climate lawsuits and regional, state or local climate policy. They also fail to address any kind of market-based mechanism or carbon pricing explicitly. NAM does call for a single, unified federal policy to address greenhouse gas emissions, which can be seen as an improvement of messaging. However, while a federal unified climate policy is essential, it cannot come at the expense of limiting states’ climate ambition.

Related Articles: A Just Transition to a Zero-carbon World Is Possible. Here’s How. | Are Countries Walking the Talk on Cutting Carbon?

Finally, the American Petroleum Institute (API) — a trade association with a history of dishonesty on climate and obstructing climate action — similarly started to improve its messaging on carbon pricing. Released in January 2021, API’s 2021 State of American Energy Report referred to carbon pricing in a vaguely supportive tone, saying that “market-based policies can foster meaningful emissions reductions across the economy at the lowest societal cost.” The report also cited carbon pricing as an example of such a policy. In March 2021, API endorsed a carbon price as part of its climate action policy framework, but it is vague and caveated: it implies that API would support a price on carbon if state and other federal climate policies, as well as a broad swath of environmental regulations, were eliminated. While the policy offers a distinct change in messaging, this caveat undermines proven climate solutions.

The shifting public positions on carbon pricing among trade associations is an interesting trend. However, only time will tell if this is an artifice of messaging or signifies real willingness to support a carbon price politically and financially.

2. Why are these changes happening now?

Perhaps more interesting than the cascade of updated climate policy positions is the impetus behind them. Several political and business dynamics are at play:

Political Dynamics

President Biden campaigned on an ambitious climate platform that he has already started to implement. Once his win was confirmed, the business community recalibrated its positions accordingly.

A stark example comes from General Motors (GM) and its stance on vehicle emission standards. In October 2019, GM joined with a handful of other automakers to back the Trump administration in a legal challenge against California’s ability to set its own emissions standards. One month later, GM committed to invest more than $27 billion in electric and autonomous vehicle product development spending between 2020 and 2025 as part of a monumental and positive shift toward vehicle electrification. On November 23, 2020, the company completely flipped its position when CEO Mary Barra announced that GM would immediately withdraw from the litigation and fully supported Biden’s robust goals to promote electric vehicles. This was roughly two weeks after Biden was announced the winner of the election.

Business Dynamics

Trade associations are meant to support and represent the interests of their members. For over a decade, many in the private sector embraced carbon pricing as a critical mechanism to fight climate change. There was support from a number of Fortune 500 companies for the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill in 2009, and many companies already have an internal carbon price. Additionally, more and more companies have been lobbying Congress to pass federal carbon pricing legislation. They recognize that such a mechanism encourages innovation and allows companies to remain globally competitive. As the drumbeat for carbon pricing grows, new trade association positions can, in part, be seen as a recalibration effort in response to member views.

3. Where will trade associations go from here?

The range of changes on carbon pricing from trade associations is notable, considering their positions in the recent past. However, these changes are still woefully inadequate in helping the United States align with the goals of achieving net zero by 2050.

The U.S. administration will shortly commit to a new nationally determined contribution (NDC), which will reset ambition for 2030 and beyond. Actions by businesses and trade association must align with that ambition. Most of the associations profiled do not specifically endorse pricing carbon, and none have endorsed a concrete policy proposal or shared details on how their positions will translate into action. At best, these developments represent a positive shift in intent. At worst, they are a calculated stalling tactic. Member companies should push their trade associations to improve their public statements further and ensure they take real action.

Carbon Pricing is the Beginning, Not the End

While well-designed carbon pricing is a powerful climate and economic policy that can spur innovation, create lasting economic growth and help the United States decarbonize its economy by mid-century, it is not a silver bullet for addressing climate change. Trade associations that are serious about climate action will also need to consider how they can support investments in clean energy, electric vehicle deployment, local air quality improvement, regulations like fuel efficiency standards, an ambitious U.S. NDC and much more. If companies and trade associations are ready to back up their positive statements and bring their political and financial force to bear, they will be welcomed and could be an incredibly influential force in creating a brighter future for all.

— —

About the Authors: Amy Meyer is an Associate in WRI’s Center for Sustainable Business. As Legislative Engagement Associate, Jillian Neuberger works closely with WRI’s Director of Government Affairs to amplify the impact of WRI’s research findings on US policy.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A factory site. — Featured Photo Credit: Patrick Hendry