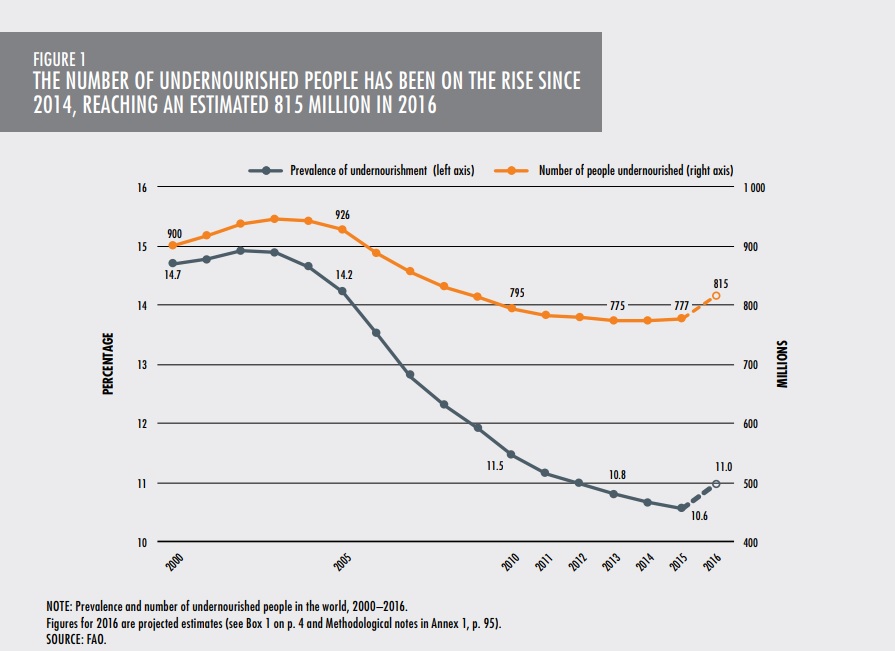

When the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) opened its 44th session in Rome on October 9, it wasn’t just another chatty UN meeting. It came with the disturbing news that global hunger was on the rise again. This was a shock. Since 2000, we had all grown complacent, every year brought the good news that hunger was slowing even though world population continued to grow, it looked like the scourge of famine was at last a thing of the past. From a high 926 million in 2005, global hunger hit a low of 777 million people in 2014.

Hunger: 815 million people were affected in 2016 – up from 777 million in 2014

But now we need to revise this cheerful view. According to the best estimates of five major UN agencies, FAO, World Food Programme, IFAD, UNICEF and World Health Organization, the trend has reversed, 815 million people were affected in 2016, slightly more than one in ten persons, as reported in the newly released UN document “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World”.

FIGURE 1: THE NUMBER OF UNDERNOURISHED PEOPLE HAS BEEN ON THE RISE SINCE 2014, REACHING AN ESTIMATED 815 MILLION IN 2016. CREDIT: FAO

FIGURE 1: THE NUMBER OF UNDERNOURISHED PEOPLE HAS BEEN ON THE RISE SINCE 2014, REACHING AN ESTIMATED 815 MILLION IN 2016. CREDIT: FAO

Undernourishment and malnutrition is clearly on the rise again. Worse, for the first time this century, outright famine was declared in South Sudan on 20 February 2017, and three more countries, Yemen, Somalia and Northern Nigeria are at serious risk, unless international aid comes to the rescue.

RELATED ARTICLE: THE RETURN OF AN OLD SCOURGE: STARVATION by Claude Forthomme

Unfortunately, the usual delays caused by donor fatigue have been recently compounded by the fear that the United States might choose to withdraw from the international community, with Donald Trump announcing plans in March to slash the US foreign aid budget by 31 percent. This would directly hit UN agencies, the World Bank and other international institutions, in particular WFP as it proposed to eliminate most US international food assistance. The announcement on October 12 by the Trump administration that the United States will pull out of UNESCO increases the adverse pressure, giving the impression to the international community that America indeed intends to give up its leadership role and retreat in isolationism.

In the photo: Muhamed Sharief Abdul, 60,eats lunch with his family inside their hut at a camp for internally displaced people in Uusgure village, Puntland, Somalia.The IDP’s in Uusgure village are pastorals who moved there after they lost their livelihood due to the current drought. They lost almost all their livestock, camels and goats, on which they depend on to survive. Credit: ©FAO/Karel Prinsloo.

But perhaps not all is lost. At the G-20 meeting in May, the Trump administration pledged $331 million as part of a $639 million relief package for South Sudan, Nigeria, Somalia and Yemen. This certainly helps WFP to deliver aid, something the head of WFP, David Beasley, a Republican politician, former Governor of South Carolina and a Trump supporter has acknowledged. And there is no question that David Beasley is doing his utmost to rally donors: he gave a rousing speech at the CFS opening on October 9, reminding his audience that “SDG #2 Zero Hunger by 2030 is just not going to happen if we stay the course that we’re on. Everybody in this room that is committed to food security and resolving hunger will have to take it to the next level.”

Yet so far funding is falling short of what is needed to avoid disaster. As of 8 October, US funding to WFP stood a little over $2 billion, making it the largest donor accounting for almost half the total received, with Germany second (at $786 million) and the UK third (at $402 million). This is good but unfortunately donations regularly fall short of what WFP is asking for, and more generally, of what is needed to build up resilience in countries suffering from protracted crises, as strikingly illustrated in the State of Food Security and Nutrition document (see figure below).

FIGURE 2: SECTORS OF IMPORTANCE TO BUILDING RESILIENCE ARE UNDERFUNDED IN PROTRACTED CRIRIS CONTEXTS CREDIT: FAO

FIGURE 2: SECTORS OF IMPORTANCE TO BUILDING RESILIENCE ARE UNDERFUNDED IN PROTRACTED CRIRIS CONTEXTS CREDIT: FAO

What is worrying is that the key message in that document – that hunger is on the rise again – barely caused a ripple in the mainstream press when it came out earlier, in mid-September. Many journalists passed up on the news. Those who did take note often didn’t give the news sufficient credence. For example, the UK Guardian, although suitably titling its article “’Alarm bells we cannot ignore’: world hunger rising for the first time this century”, highlighted early in its piece what a senior economist at FAO had said, that “it was hard to know whether the increase was a blip or marked the reversal of a long-term trend”.

A blip, really? Given the context of an increasing trend in complex, long-lasting conflicts around the world, accelerating climate change and the rising number of refugees and displaced persons, it is hard to believe that we are facing just a “blip”. But now, as the CFS is meeting in Rome, there is hope that the warning will be heeded by the international community that counts.

In the photo: Opening Ceremony of the 44th Session of the Committee on World Food Security, FAO Headquarters, (Plenary Hall). Committee on World Food Security, 44th Session (CFS 44), 09-13 October 2017, FAO headquarters. Credit: ©FAO/Giuseppe Carotenuto

The CFS is attended by hundreds of participants, not just government delegates and observers (133 countries present this time) but also representatives from civil society. At the CFS opening on the morning of October 9, the FAO plenary hall was filled to capacity, all 1,180 seats occupied, with many people left standing.

Civil society at the CFS comes in two forms (that sometimes do not agree with each other): One is the so-called CSM, “Civil Society Mechanism” which pulls together 11 “constituencies”: NGOs and associations of smallholders farmers associations, pastoralists/herders, fisherfolks, Indigenous Peoples, urban food insecure, landless, agricultural and food workers, women, youth and consumers, in total, some 380 million people; the other is the PSM, the “Private Sector Mechanism” that includes the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and hundreds of foundations, charities and business-sponsored associations. Everyone participates through these “mechanisms” and is given a chance to add to the debates and help shape policy decisions, such as the right to food – policy decisions that are called “CFS products”. This is how the CFS is opened to all sectors of society, making it a trailblazer, the first of its kind in the United Nations system though now others are following the CFS “model”.

And this year, the CFS got a revamped version of the usual report it receives on food security issues, known under the acronym “SOFI” (derived from its title, “The State of Food Insecurity in the World”). But now, with a new title underlining its widened scope, the document has become far more important: For the first time, it is published in partnership with World Health Organization and UNICEF, in addition to the original SOFI authors, the Rome-based UN agencies (FAO, WFP and IFAD).

And this year, the CFS got a revamped version of the usual report it receives on food security issues, known under the acronym “SOFI” (derived from its title, “The State of Food Insecurity in the World”). But now, with a new title underlining its widened scope, the document has become far more important: For the first time, it is published in partnership with World Health Organization and UNICEF, in addition to the original SOFI authors, the Rome-based UN agencies (FAO, WFP and IFAD).

The reason for this expansion is two-fold: one is the inclusion of nutrition issues following recommendations from ICN 2, the 2014 international conference on nutrition that launched the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016-2025); and the other is the need to monitor progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals of Agenda 2030, in particular SDG Target 2.1 (ending hunger) and SDG Target 2.2 (ending all forms of malnutrition – including child stunting, obesity and anaemia among women of reproductive age).

The document was presented by FAO Director Marco Sànchez Cantillo who attributed the slowdown in the progress of the fight against hunger to three “drivers”:

- Conflicts

- Climate change and extreme weather events

- Economic slowdowns and adverse impacts on social protection policies

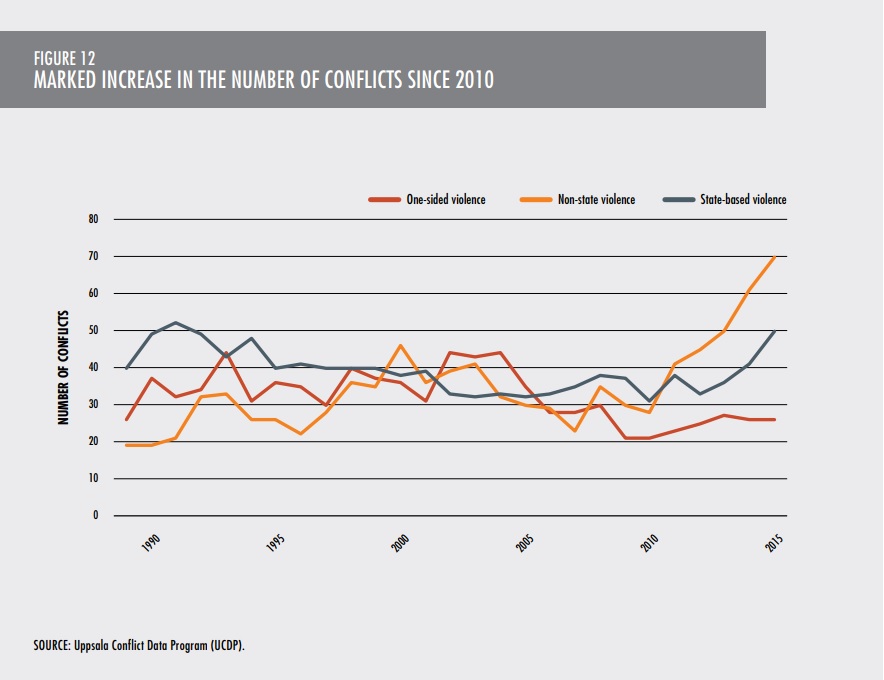

The number of conflicts has risen sharply between 2010 and 2015 (see figure below) and conflicts have become more complex and intractable, spilling across borders. 489 million people and the majority of stunted children under five years live in countries affected by conflict – that is 122 million children or 75 percent of the total. These are chilling statistics that give a measure of how hard it will be for these populations to recover, particularly with a generation of stunted children that will not grow into fully able-bodied adults.

FIGURE 12: MARKED INCREASE IN THE NUMBER OF CONFLICTS SINCE 2010 See p. 32

FIGURE 12: MARKED INCREASE IN THE NUMBER OF CONFLICTS SINCE 2010 See p. 32

Conflicts undermine livelihoods and drive displacement. The same can be said of climate change and extreme weather (droughts, floods). Rural areas are the hardest hit, disrupting food systems and causing populations to flee. The number of people displaced is at its highest in decades, with an unprecedented 65.6 million uprooted from their homes in 2017.

In short, achieving zero hunger and ending undernutrition, as called for by the SDGs, could be out of reach for many of the countries hit by conflicts or natural disasters (or both, the case of Syria).

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: ICN 2: WHERE A POPE, A QUEEN, A KING, A PRINCESS AND MELINDA GATES COME TOGETHER by Claude Forthomme

Proposed Solutions

First, we need to admit that it isn’t “business as usual”, we cannot wait for peace, we must use a “conflict sensitive” approach to build “resilient livelihoods”. That means adopting a fully “integrated” approach, going beyond humanitarian assistance, hitting on all the sectors that contribute to a population’s “resilience” to steer people back on a path to “normal” development.

This requires building up people’s capacity to resist shock – whether caused by human-made or natural disasters – and providing them with the means to work and support their families. Donors should be ready for multi-year, multi-sectoral investment cycles to prop up agriculture and economic infrastructure, food systems, education, health, shelter and non-food items, water and sanitation, protection of human rights and the rule of law. A long list, but a necessary one, any shortcoming in one sector affects adversely all the others.

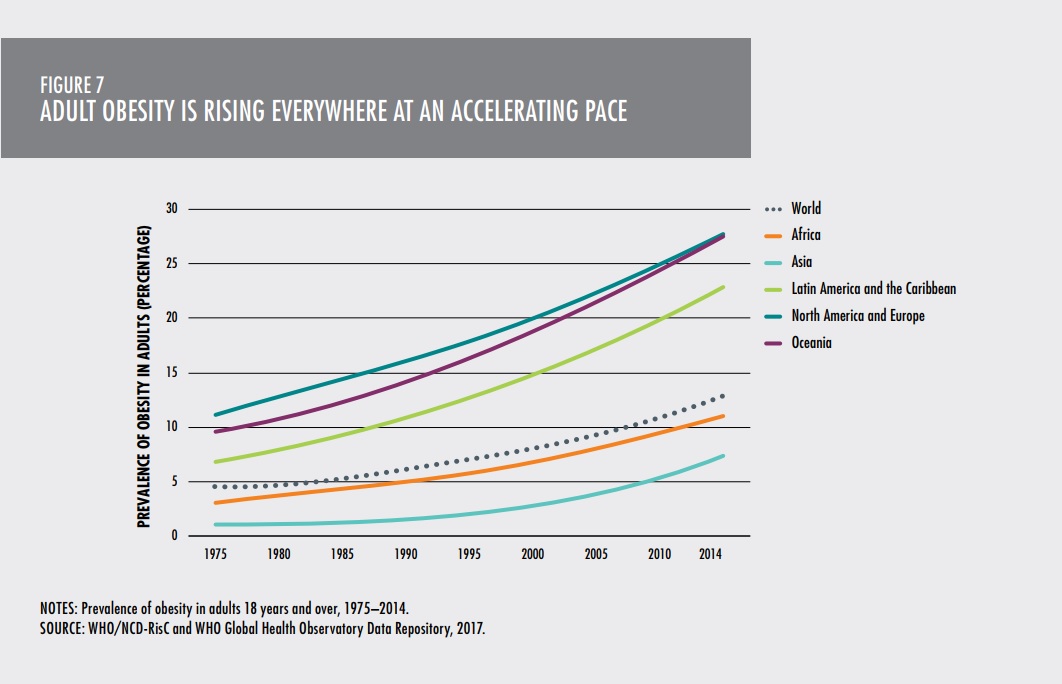

The second part of the document “The State of Food Security and Nutrition” makes a good case on how to proceed to address nutrition issues in disaster-stressed countries. But it is silent on how to address the problem of obesity, though it amply documents its relentless growth, including among children. Worldwide, an estimated 41 million children under five, about 6 percent of the total, were considered overweight in 2016, up from five percent in 2005. The global prevalence of obesity among adults doubled between 1980 and 2014, with more than 600 million obese adults in 2014, with the problem most severe in Northern America, Europe and Oceania.

FIGURE 7: ADULT OBESITY IS RISING EVERYWHERE AT AN ACCELERATING PACE

FIGURE 7: ADULT OBESITY IS RISING EVERYWHERE AT AN ACCELERATING PACE

The Obesity Issue

While no prescription on how best to address the problem of obesity is included, there are some suggestions made in another document presented at the CFS, a report by the CFS-appointed Panel of High Level Experts (HLPE, chaired by Patrick Caron) on Nutrition and Food Systems (HLPE Report no.12). In this document, it is argued that, taking together the two major nutrition issues, obesity and undernourishment, we are facing a situation where, globally, “one person in three is malnourished today and one in two could be malnourished by 2030 if nothing is done.”

What can be done to address obesity? The document highlights two concrete priorities for action:

- improve the physical and economic access to healthy and sustainable diets; and

- strengthen consumers’ information and education to enable healthier food choices.

These are long-term actions that will require strong political commitment if any improvement is to be achieved. It’s not just a matter of spreading nutrition information. For example, the problem caused by “food deserts” in America will need to be addressed. And that is linked to broader, difficult-to-solve poverty and income inequality issues.

RELATED ARTICLE: HUNGRY FOR CHANGE by Providenza Loera Rocco

It is hard to escape the impression that the UN system, long geared to address development problems in low-income countries, cannot easily turn around and come to the rescue of HICs (High-Income Countries).

For example, the latest issue of the FAO flagship report, SOFA 2017 (The State of Food and Agriculture – Leveraging food systems for inclusive rural transformation) that was also introduced at the CFS, makes the case that rural areas are not in fact “poverty traps”, that reaching the SDGs is possible if their economic potential is unlocked. There is compelling evidence that, since the 1990s, rural transformations in many countries have led to an increase of more than 750 million in the number of rural people living above the poverty line.

For this “inclusive rural transformation” to happen, several innovative strategies are suggested, notably using an “agro-territorial approach” to strengthen the nexus between rural areas and small towns, building “agro-corridors” for lines of transportation and “agroclusters”. (Disclosure: as a project evaluation specialist working twenty years in developing countries, this is an argument that I have long believed in, that agriculture is the first step to development in most low-income countries). But one must observe that while the document does an excellent job of addressing the plight of the rural poor and undernourished, it contains not a word about obesity.

Yet, as pointed out in the CFS/HLPE document mentioned above, modern food systems do play a role in causing obesity. One is however left with the impression that much more research is needed to come up with satisfactory, workable solutions. This is something UN agencies could work on but, if something is to happen, the high-income countries facing an obesity epidemic also need to come on-board and cooperate to identify the best strategy to address it.