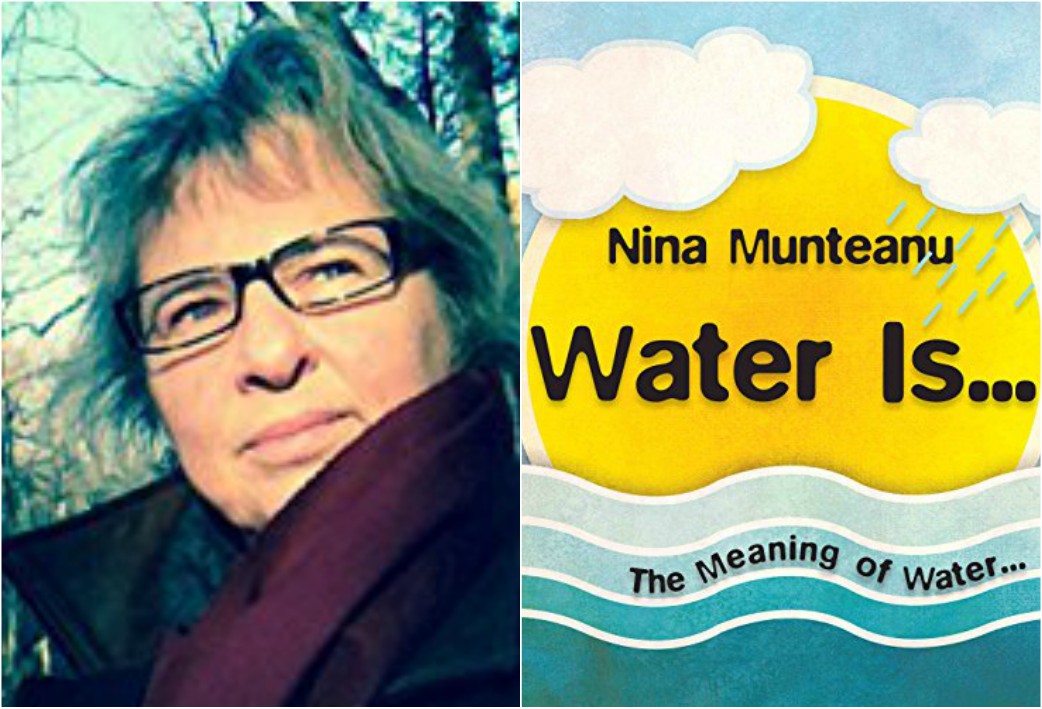

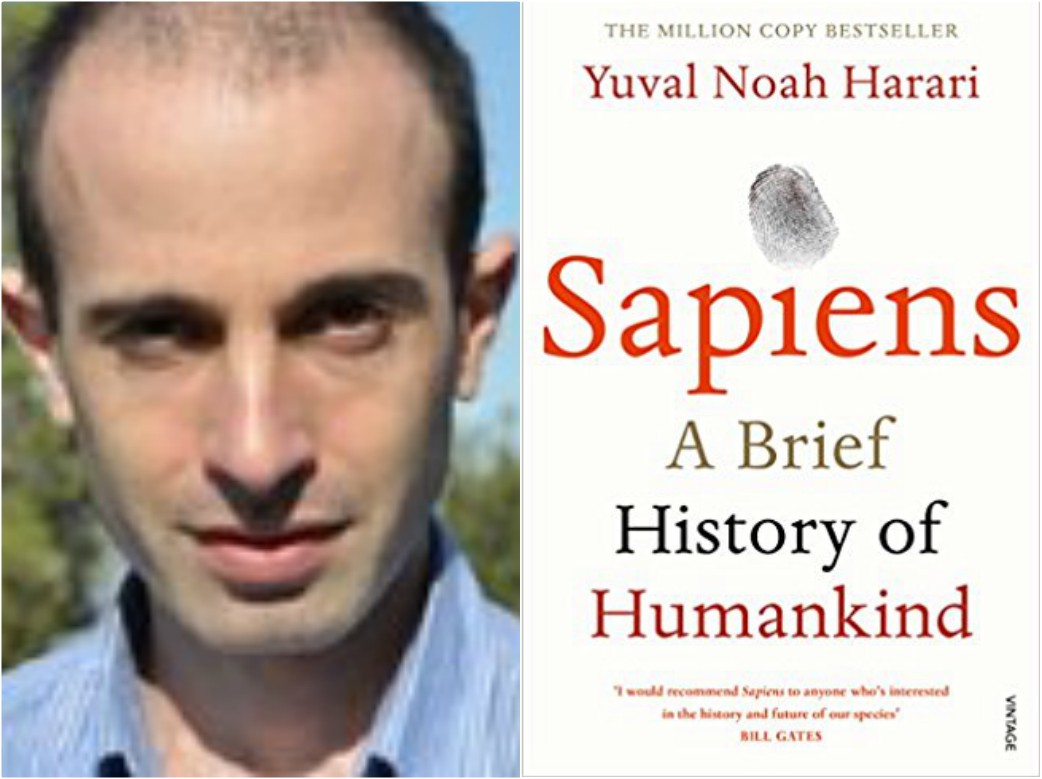

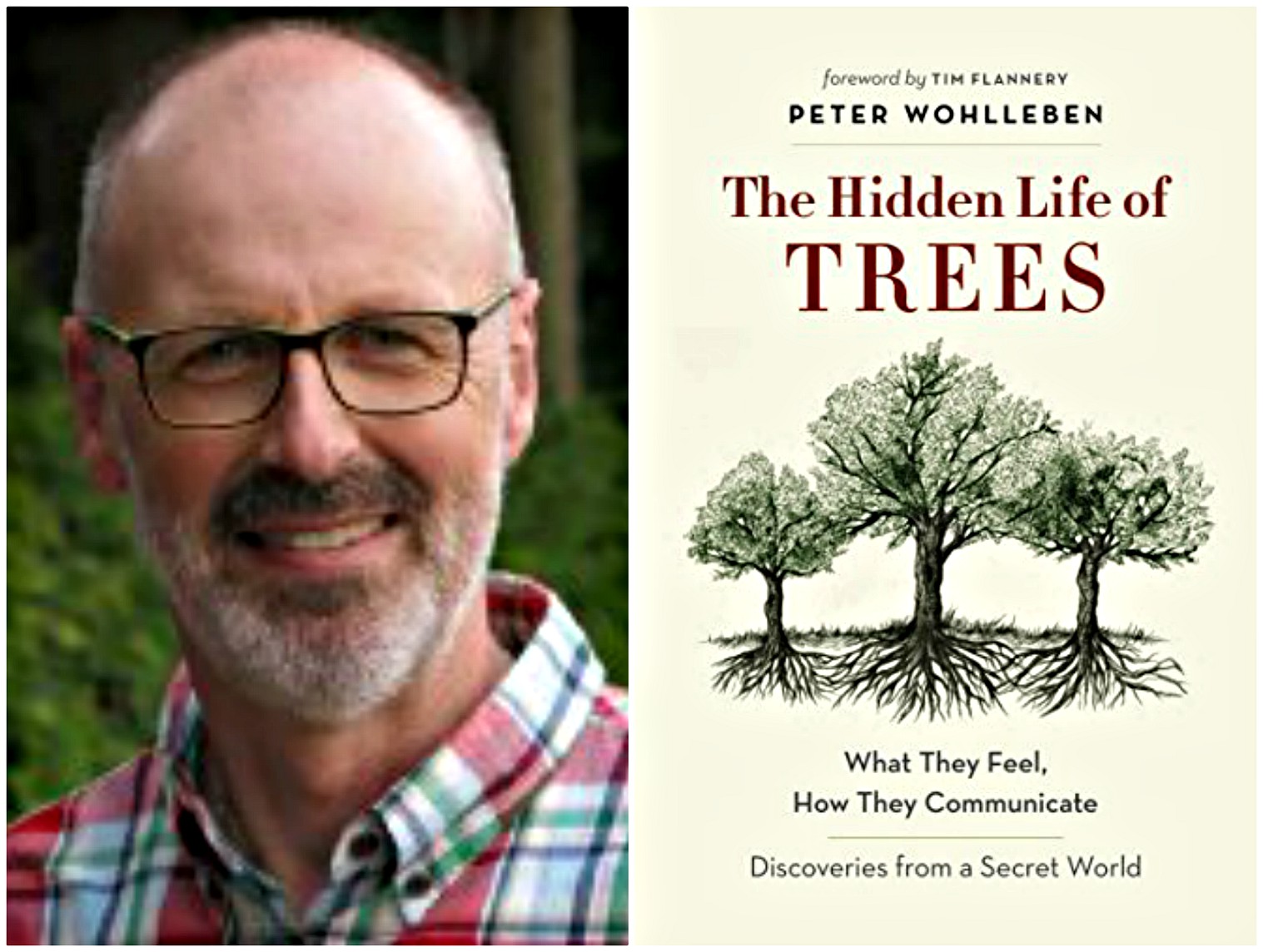

BOOK REVIEWS: The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt’s New World by Andrea Wulf, Knopf: New York, 2015, 496 pages; The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How they Communicate by Peter Wohlleben, translated by Jane Billinghurst, Greystone Books: Vancouver, 2016; Water Is…The Meaning of Water by Nina Munteanu, Pixl Press: Vancouver, 2016; Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari Harper Collins: New York, 2015

Do we live in a world of wonder where Nature ultimately calls the shots or a world of reason where Homo Sapiens are in control?

Or, to put it another way: Is Nature dependent upon our definitions of it, or does it both precede and transcend human consciousness? Does the term “Anthropocene” signal an apocalyptic shift that places us at the center of the Universe and if so, is the death of Nature upon us, or are we mistaken? Could it be just another instance of homo sapiens’ hubris, overvaluing our capabilities for destruction?

I recently came across four books, that taken together, help answer these questions. What follows is an account of the insights to be gained from each one.

The books concern four very different personalities: Alexander von Humboldt, an 18th century Prussian scientist, the father of ecology; Peter Wohlleben, an ecologist who worked over twenty years for the forestry commission in Germany and Nina Munteanu, a limnologist, university teacher and award-winning ecologist.

All three are scientists who made close observations of nature that filled them with wonder at the complexity of its processes. The fourth, an Israeli historian, Yuval Noah Harari has taken a dramatically different stance: He deplores our epoch when human egos have run amuck, putting Nature itself in peril.

1. World of Wonder: Humboldt, the First Ecologist, Saw Nature as a Process

At the start of scientific inquiry in the eighteenth century, the natural world was presumed to have always been exactly the same, unchanged from the beginning of Time. It was widely believed that God, the celestial watchmaker, had developed earth’s intricate workings, set them going, and had then just stepped back and let them run. Enlightenment thinkers understood nature and the cosmos as static, constituted in the same way and working exactly as they had from the beginning of the world.

Then along came Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), genius, polymath, explorer and keen observer of botanical phenomena, who found nature in a constant state of change.

In The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt’s New World, design historian and author Andrea Wulf has written an excellent biography that is also a stunning contribution to the intellectual history of science.

A keen botanist, who was sometimes reluctantly forced to support himself as a courtier to his patron, the Prussian King Frederick II, Humboldt was ebulliently enthusiastic, tireless, curious about everything and a non-stop talker.

He visited and charmed a wide swathe of European and American intellectuals including Thomas Jefferson, Louis-Hector Berlioz, William Wordsworth, Prince Albert, and Charles Darwin. The latter was so entranced with his methodology and observations that he took all seven volumes of Humboldt’s autobiography along with him on the HMS Beagle, the ship on which he traveled for five years around the word, a trip that launched him into his scientific investigations.

Von Humboldt’s deepest passion was for traveling as far away from Europe as he could get in order to study plants in different climates. After comparing the flora and fauna of South America and Europe, he proved that species change according to their material circumstances, like the altitude on a mountain range or the incursion of a new species into their area.

“Bildungsreich,” explains Wulf, is a “‘formative drive’, a force that shaped the formation of bodies. Every living organism, from humans to mould, had this formative drive. For Von Humboldt, nothing less was at stake in his experiments than the undoing of what he called the ‘Gordian knot of the processes of life.’” (24)

The key word here is “processes” as opposed to stasis.

His discovery that natural phenomena are inter-influencing elements of an interdependent whole, connected and interacting along an “invisible web of life,” made Humboldt the first ecologist.

He was also the first to notice human destruction of the natural world: in his description of “imperial ambitions that exploited colonial crops,” for example, he concludes that “the ‘restless activity of large communities of men gradually despoil the face of the earth’” (289).

During Humboldt’s career, scientists were quite rigid in seeking to erase emotional biases from their conclusions. Humboldt on the other hand, stunned by wonder at what he was discovering, described his conclusions with considerable emotion. He was a proponent of the Naturalphilosophie espoused by his great friends Wolfgang Goethe and Frederich Schelling.

His most influential book, Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe (begun in 1834 when he was sixty-five), was so permeated by his love of nature and delight in its processes that it influenced poets and writers like Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, who radically altered his vision of nature after reading it. Wulf compares the earlier and later drafts of Walden, demonstrating that what had been a critique of American commercial culture became a book in which Thoreau was moved to “look at Nature with new eyes.” (260)

2. World of Wonder: The Hidden Life of the Forest Uncovered by Peter Wohlleben

Contemporary German forest ranger Peter Wohlleben belongs to the same school of Naturalphilosophie as Humboldt, bringing a similar sense of curiosity and wonder to his botanical observations.

As a result, scientists have criticized his widely popular 2015 work The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How they Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World for tainting his results with “anthropomorphism,” despite the end notes from Dr. Suzanne Simard, Professor of Forest Ecology and the University of British Columbia, which validate his findings.

Wohlleben observes how trees (even of different species) try to heal each other: when one tree senses an infection or infestation, it sends both warnings and shots of healing chemical compounds to others growing nearby. “It appears that the nutrient exchange and helping neighbors in times of need is the rule, and this leads to the conclusion that forests are superorganisms with interconnections much like ant colonies.” (3)

Wohlleben claims that trees also “talk” to each other by sending electrical impulses along an underground network of fungi roots and tendrils that “operate like fiber-optic internet cables.” (10).

As he chopped down trees and sprayed the forest with chemicals, Wohlleben became uncomfortable with his vocation. He sent objections and proposed alternative methods to his superiors, who refused to listen; he began to suffer from depression and decided to quit his job and emigrate to Sweden. Just in time, the town of Hummel decided to annul its state contract, reconstitute itself as a private preserve, and hire him to implement his innovations.

Like Humboldt, Wohlleben understands human beings as embedded in a web of being where each element – fungi with trees, forests with human breathing – interact in intricately calibrated processes, an wholistic ecology which we degrade at our peril.

3. World of Wonder: Nina Munteanu’s Hidden Properties of Water

In the same way that Peter Wohlleben approaches the hidden life of trees with a combination of scientific observation and enthusiastic wonder, in Water Is…The Meaning of Water, Canadian limnologist Nina Munteanu observes the hidden properties of water with a scientist’s eye for detailed processes and a sense of amazement at their intricacies.

Echoing Humboldt’s discovery of the interwoven multiplicities of nature, she transcends “Newtonian Physics and Cartesian reductionism aimed at dominating and controlling Nature”:

“Science is beginning to understand that coherence, which exists on all levels – cellular, molecular, atomic and organic- governs all life processes. Life and all that informs it is a gestalt process. The flow of information is fractal and multidirectional, forming a complex network of paths created by resonance interactions in a self-organizing framework. It’s stable chaos. And water drives the process” (190-191).

Munteanu shares some of Humboldt’s affinities. “Goethe,” she observes, “an accomplished polymath and scientist, said of the conventional approach in science: ‘Whatever you cannot calculate, you do not think is real'”(23). She considers herself “one of the mavericks of the scientific community,” attentive to what her more conventional colleagues term “weird water” – aspects of the peculiar ways that water escapes from stasis or chemical inertia.

Like Humboldt and Wohlleben, Munteanu analyzes the constant motion and metamorphoses of the material world, agreeing with Quantum physicist David Bohm’s “universal flux” describing “a dynamic wholeness-in-motion in an interconnected process” (170).

Water, in Munteanu’s findings, demonstrates “the Gaia Hypothesis,” which “proposes that living and non- living parts of our planet interact in a complex network like a super-organism. The hypothesis postulates that all living things exert a regulatory effect on the Earth’s environment that promotes life overall” (89). “Much of nature – if not all of it – embraces this hidden order, which I describe as ‘‘stable chaos’” (167).

In addition to providing a gripping analysis of water science, her book provides an encyclopedic trove of quirky observations, like how Galileo understood water flow, the Chinese character for water, Leonardo da Vinci’s water drawings, the Gaia Hypothesis, and David Bohm’s theory of flux.

4. World of Reason: Harari’s Despair in the Anthropocene

In his early chapters of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Israeli Historian Yuval Noah Harari finds our hunter/gatherer or forager stage, which he terms “the original affluent society,” quite appealing. We ate a wide variety of foods, owned very little stuff, moved about seasonally in bands of friends and relatives, were much healthier than our agricultural and industrial successors, and had a better grasp of facts:

“the average forager had wider, deeper and more varied knowledge of her immediate surroundings than most of her modern descendants” (49).

We were nonetheless embedded in a vast and powerful natural world before whose uncontrollable forces we felt small and puny. We coped with this sense of helplessness by endowing tree and water, sun and stone with powerful animistic properties – that is, we projected spirit into them – which we then sought to propitiate. I use italics to indicate Harari’s vision of inspiriting nature as a human construction, as opposed to people appreciating intrinsic (“essential”) qualities of bear and stone, tree and river.

Harari sees Sapiens, especially in our religious institutions, as destructively self-serving; even in our earliest history he suspects we were responsible for the extirpation of the Neanderthals. Everywhere we settled, mammoths and other megafauna suffered mass extinction. “The historical record,” he concludes, “makes Homo Sapiens look like an ecological serial killer” (67).

Harari documents “the cognitive revolution” as a leap forward in human sapience about 70,000 years ago; but it was all downhill from there.

Agriculture brought social stratification and enslavement along with cruelly hierarchical religious institutions; bands widened into complex cultures which demonized and slaughtered each other. Culture became “a kind of mental infection or parasite, with humans as its unwitting host.”

The industrial revolution, while it “liberated humankind from dependence on the surrounding ecosystem,” provided no lasting benefit to the human race: “Many are convinced that science and technology hold the answers to all our problems…” but, “Like all other parts of our culture, it is shaped by economic, political and religious interests” (350). “We constantly wreak havoc on the surrounding ecosystem, seeking little more than our own comfort and amusement, yet never finding satisfaction” (215).

Nature Rising?

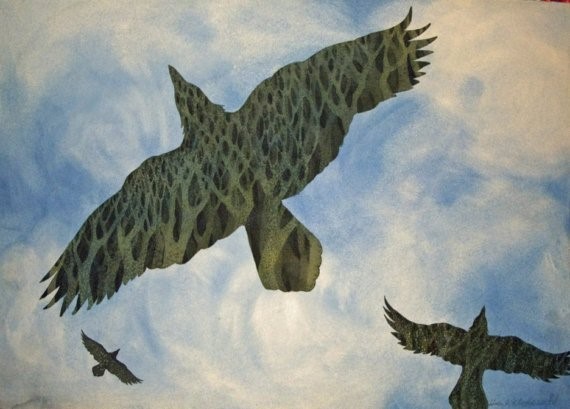

Nature Rising by Helen Klebesadel Watercolor. Permission from artist. In this painting the flying crow contains the forest trees, representing the interconnection of all parts of nature, including the human element.

Unsurprisingly, Harari accepts the newly popular term “Anthropocene” to describe the times we live in.

As Kurt Caswell in a review of Anthropocene Blues writes:

“The central question of the Anthropocene is whether or not our species is ‘irreversibly transforming the Earth’s biological, geological and chemical processes,’ in the words of chemist Paul Crutzen, the first scientist to use the term about a decade ago.”

“Usually,” Caswell explains, “epochal changes play out geologically over millions rather than thousands of years. The Holocene is only a little over 10,000 years old — the shortest epoch so far.” And he underlines how arbitrary the term is: “The group that decides such shifts and changes, The International Commission on Stratigraphy, has not officially signed off on the term.”

Yet people love it, he notes that the “use of ‘Anthropocene’ has exploded among intellectuals and activists who find it a useful cudgel to beat our species about the head and shoulders. And perhaps we deserve it.”

Is dubbing our age ‘The Anthropocene’ more hubristic than scientific and more apocalyptic than geological?

With the minds of scientists and hearts of wonder, Humboldt, Wohlleben, and Munteanu understand the botanical and hydrological phenomena they study as independent of human scrutiny and, therefore, out there, coherent in and of themselves, both anteceding and transcending human thought.

Where Harari privileges Sapiens with apocalyptic capability, these three scientists seem closer to the Gaia hypothesis that understands nature as alive with enormous life, probably capable of outlasting human folly.

Within the Gaia framework, to be sure, human beings act deleteriously upon the system, our intemperate carbon emissions causing nature to react with epic storms, enormous wildfires, and vast floods.

But aren’t these tumultuous catastrophes demonstrative of nature’s ability to rise over and against what we throw at it?

Global warming may end civilization and perhaps the human species along with so many others we have destroyed, but are human beings really capable of engineering the destruction of the planet? I doubt it.

Nature might very well rise in some unimaginable way before we do our species in altogether. Then, even if our much vaunted technology becomes useless and we are forced back to our puny-before-nature stage as hunter/gatherers (which was when, after all, Harari found us at our healthiest and smartest and most adaptive), we might use our hard-earned wisdom to achieve better ecological balance the next time around.