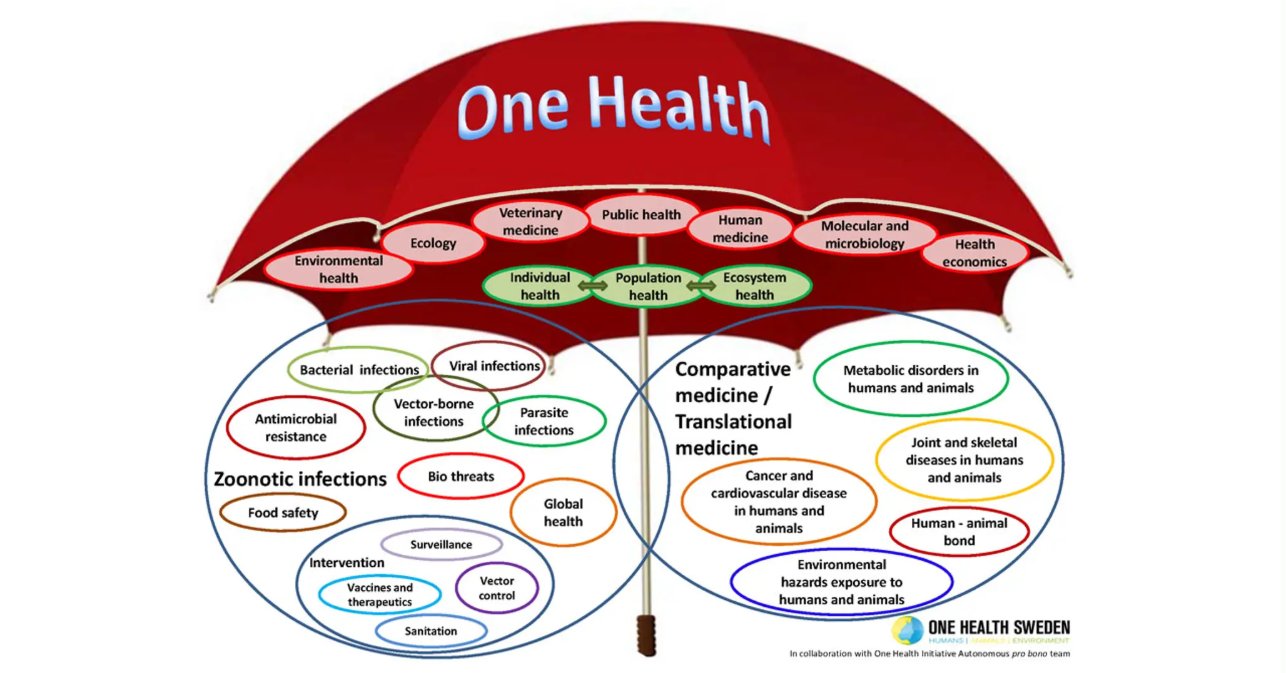

One Health can be a complex and sometimes jargon-filled concept. Put simply:

“One Health is the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals, plants and our environment.”

To simplify the message for political leaders and their constituents of how “One Health implementation will help protect and/or save untold millions of lives in our generation and for those to come,” we propose to:

- Use economic arguments to demonstrate that proactive, multisectoral approaches are cheaper in the long run than reactionary, fragmented responses. The immense economic costs of COVID-19 were mitigated using One Health measures and notably could/would prevent or lessen future pandemics.

- Emphasize how threats like zoonotic diseases and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are national security issues that require a unified federal response. Highlight the role of One Health in protecting food supplies, fortifying against bio-threats, and safeguarding the military from global health crises.

- Discuss the challenges of inter-agency cooperation, such as siloed funding and differing priorities. This article includes a clear, concise plan to help overcome these hurdles.

Build a broad, worldwide One Health interdisciplinary coalition

Preparedness for future health crises utilizing One Health is a fiscally responsible, long-term investment. The core principle of One Health is collaboration, so the advocacy effort should reflect this by creating a diverse and influential coalition. Including non-health sectors requires reaching out to leaders and organizations outside of traditional medical, veterinary medical, public health, biomedical fields, etc.

Partnering with groups representing agriculture, environmental protection, wildlife conservation, transportation, and international relations widens the base of support and presents One Health as a national security, food safety, and economic remedial issue, not just a public health one. Engaging with state health departments and local leaders who have responded to real-world One Health issues, like an avian influenza outbreak or a waterborne disease event, allows their experiences to offer tangible, district-specific examples that members of legislative bodies (e.g., in the U.S. Congress) can relate to.

The One Health concept/approach has demonstrated a clear economic benefit and practical applications through tangible documented accounts with supportive data for centuries, especially during the latter half of the 20th and early decades of the 21st. Being efficaciously and expeditiously prepared for future health crises utilizing One Health is fiscally responsible and a superior long-term investment.

Here is how One Health implementation works:

“The One Health concept is a worldwide strategy for expanding interdisciplinary collaborations and communications in all aspects of health care for humans, animals and the environment. The synergism achieved will advance health care for the 21st century and beyond by accelerating biomedical research discoveries, enhancing public health efficacy, expeditiously expanding the scientific knowledge base, and improving medical education and clinical care. When properly implemented, it will help protect and save untold millions of lives in our present and future generations.”

Turning to One Health initiatives

Utilizing documented One Health initiatives that provide tangible, supportive data showing positive outcomes in disease control, cost efficiency, and environmental health, supported by U.S.A., European, and other nations’ lawmaking legislation, is unquestionably “the way to go.”

Projects that demonstrate the benefits of cross-sectoral collaboration between human, animal, and environmental health experts include:

- Multiple U.S. projects, often under the “One Health” framework such as the National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases (2025–2029), have evolved. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of the Interior (DOI), and 21 other federal agencies were congressionally mandated to a strategic framework to improve the nation’s preparedness and response to zoonotic diseases (i.e., illnesses shared between animals and humans) and other interconnected health threats. Benefits were enhanced with coordination by providing a structured platform for cross-agency communication, training, and information sharing to prevent, detect, and respond to outbreaks. This improved surveillance by formalizing the integration of human, animal, and environmental health data to better monitor disease threats. Holistic (comprehensive, all-inclusive) preparedness essentially establishes a system that can be applied to other complex public health challenges beyond zoonotic diseases.

- COVID-19 pandemic response witnessed collaborations among public health, animal health, and environmental health officials from over 20 federal agencies, state and local partners, and universities. The CDC coordinated the One Health Federal Interagency Coordination Committee to respond to the pandemic. The group investigated the spread of SARS-CoV-2 between people and animals, developed guidance, and shared research. Combining surveillance and genomic data from human and animal samples helped improve understanding of how the virus affected different species and of its transmission. It also facilitated the rapid development of guidance for companion animals, wildlife, and food production animals.

- The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) established effective collaborators from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and CDC as well as state and local agencies. NARMS is a surveillance system designed to track antimicrobial resistance in humans, animals, and retail meat. The EPA leads the environmental component, including a project to monitor surface water for AMR. This highlights a holistic understanding by revealing how antimicrobial resistance spreads across sectors, including into the environment (i.e., soil and water). Targeted interventions provide data for more effective strategies to curb the growing threat of AMR.

- One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS) collaborators are from CDC, EPA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and state partners. This project is an integrated surveillance system for reporting human and animal illnesses associated with harmful algal blooms (HABs). These toxic algae can affect drinking water, recreational water, and seafood. Such integrated data creates a better national estimate of the public health burden of HABs by combining human and animal health reports. It allows NOAA to contribute data on environmental conditions to help predict and prevent HABs.

- Environmental health projects measuring wildfire smoke and air quality engage collaborations among the EPA, the USDA’s Forest Service, and federal, state, and community organizations. Collaborators share resources and data through platforms like AirNow to identify and communicate public health risks from wildfire smoke exposure. Timely public information, communicated with the assistance of “public affairs” professionals, allows communities to prepare for and reduce health risks before and during wildfires. It fills data gaps by integrating PurpleAir sensor information to improve local air quality monitoring.

- Academic and community projects like Midwestern University’s One Health Initiative: Students and faculty from various health colleges (e.g., human medicine, veterinary medicine, pharmacy, speech-language pathology) collaborate. Midwestern University integrates One Health principles into its curricula, interprofessional activities, and community outreach. Examples include joint disaster preparedness training, a canine rehabilitation program involving physical therapy and veterinary medicine, and a partnership with a domestic violence shelter to address pet abuse. This type of “enhanced education” provides a more comprehensive education that prepares future health professionals to work collaboratively. It offers innovative solutions to community challenges by recognizing the human-animal-environmental health links, such as the connection between pet abuse and domestic violence.

- Rabies elimination in Sri Lanka: The coordinated One Health approach to rabies control in Sri Lanka involved cross-sector collaboration and produced clear, positive results, demonstrating the effectiveness of the model. Rabies was endemic in Sri Lanka, causing widespread infections and deaths among both humans and animals. Before this coordinated effort, rabies was widespread and difficult to control. Animal infections were prevalent in dog populations, the primary vector for human cases. The One Health solution was a collaborative effort launched with experts from multiple disciplines. Mass canine vaccination was the key strategy involving the large-scale, strategic vaccination of the dog population to control the spread of the virus at its source. Human vaccination and public awareness incorporated efforts that included human post-exposure vaccination prophylaxis and public awareness campaigns about rabies prevention. Dog population management experts also implemented effective dog population management strategies. Cross-sectoral collaboration meant that this initiative integrated the expertise and resources of health officials, veterinarians, and public health experts (epidemiologists). Documented data and outcomes from this initiative showed a significant and sustained reduction in human rabies cases. Tangible results developed following the implementation of the One Health strategies; human fatalities from rabies dropped to less than 50 in 2012. The program’s success provided a quantifiable and documented measurable impact and account of the benefits of using a multi-disciplinary approach to address a complex zoonotic disease.

- Many other documented One Health accounts, including other case studies that provide further supportive data on the positive impact of One Health initiatives like Hendra virus control in Australia. The Hendra virus, transmitted from bats to horses and then to humans, had a high fatality rate. A One Health approach led to the development of a vaccine for horses and the implementation of an advanced surveillance system. The initiative involved government agencies, veterinarians, and public health officials. Between 1995 and 2023, nearly 100 cases were reported in horses, all of whom died, while only seven cases occurred in humans. This demonstrated the effectiveness of the vaccination and surveillance program in mitigating the risk to humans.

- One superlative biomedical research example of One Health can be found here.

More extensive, detailed examples have been documented online in major professional journals, books, and One Health devoted websites. These include major One Health sections on websites of international entities like the Quadripartite (WHO, FAO, WOAH, UNEP) and prominent national government agencies like the U.S. CDC. Academic centers and non-profit commissions also serve as important sources for information and collaboration.

International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), which is part of the Quadripartite, focus on the human health component of One Health. Its website contains information on policies, strategies, and programs designed to improve public health outcomes globally by fostering collaboration across sectors. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), another partner in the Quadripartite, emphasizes the link between agricultural practices, food safety, and the health of people, animals, and the environment.

The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), formerly OIE, leads global efforts to improve animal health and welfare, with its website detailing its work on preventing and controlling disease, including zoonoses, through a One Health approach. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the newest member of the Quadripartite, focuses on the environmental dimension of One Health, addressing issues like ecosystem health, climate change, and pollution.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) is a regional office of the WHO, which details One Health action tracks for the Americas region, including controlling zoonotic diseases, addressing antimicrobial resistance, and strengthening capacities for prevention and response. In particular, U.S. government agencies, beginning with the CDC’s dedicated One Health website section, provide a wealth of information and resources, including updates on initiatives, publications, outbreak investigations, and training materials. It explains how the CDC connects human, animal, and environmental health.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agencies, such as the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), have One Health pages that focus on protecting the health of domestic animals, wildlife, and plants. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website includes One Health resources that address the close links between ecosystem health and human and animal health.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and the University of California, Davis announced a new partnership program to advance and expand the application of “SpillOver,” a viral ranking application that directly compares the risks posed by hundreds of animal and human viruses. The database ranks hundreds of virus, host, and environmental risk factors to identify viruses with the highest risk of zoonotic spillover from wildlife to humans and to highlight those most likely to spread and cause human outbreaks.

One Health non-profits and academic initiatives like the One Health Commission, a non-profit organization, are dedicated to raising awareness and educating audiences about the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration for the health of all living things. It offers an online bulletin board with opportunities for education and employment.

One Health Initiative, a website run by private individuals, provides a historical perspective and promotes the One Health concept globally. The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, a research institution, has projects dedicated to One Health, focusing on preparedness and global health security. Additionally, the U.S. Military has embraced One Health by incorporating it into relevant public health programing.

Professional and specialized websites include American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), which details the crucial role veterinarians play in the One Health approach, in partnership with human health and public health professionals, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s website section explaining its role in One Health, particularly in areas concerning animal and veterinary health.

Concrete Legislative Action is a must-do

- Successful federal initiatives already embodying the One Health approach, as mentioned in the National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases, which the U.S. Congress directed the CDC, USDA, and DOI to develop. This per se demonstrates that the concept is not a new or foreign idea but a logical extension of existing work.

- Leaders in the One Health movement can provide specific bills and begin working with congressional staffers to develop or support unambiguous legislation. This could include a bill to create a permanent federal One Health office (the U.S. CDC already has an extraordinary, productive One Health office), codify interagency coordination, or authorize sustained funding for collaborative research.

- Leaders of the One Health movement must begin to leverage timing. They should use relevant events — such as new virus outbreaks, agricultural crises, or environmental disasters — to underscore the urgency and relevance of the legislation.

Acting together, the global One Health community, leaders, and leading One Health organizations worldwide can fast-forward implementation of the One Health concept/approach. It would “…help protect and/or save untold millions of lives [worldwide] in our generation and for those to come.”

** **

This article was authored by Laura H. Kahn, MD, MPH, MPP ▪ Bruce Kaplan, DVM ▪ Thomas P. Monath, MD ▪ Thomas M. Yuill, PhD ▪ Helena J. Chapman, MD, MPH, PhD ▪ Craig N. Carter, DVM, PhD ▪ Becky Barrentine, MBA ▪ Richard Seifman, JD, MBA.