The 2010s are coming to a close. Reviewing the decade, what can we say about the future? A tech person will look at technological progress (stunning). A sociologist will look at cultural diversity (explosive). My take (disclosure: I’m an economist) is that this decade, with growing income inequality, saw an unprecedented number of billionaires taking center stage. “Good” billionaires like Bill Gates concerned about climate change and equity, “bad” ones like Betty De Vos, defunding and dismantling America’s public education system.

This fact alone, the rise of the billionaires, will shape our future, for better (a peaceful, balanced world) or for worse (climate Armageddon).

Much depends on what kind of billionaire takes power. Some of them can be alarmingly aggressive, for example, Trump ordering the summary execution of Iran’s General Qassem Suleimani killed last Friday at Baghdad airport via a drone strike. A strike that could escalate dangerously in the Middle East’s explosive environment.

Unsurprisingly, the 2020 campaign for the US presidency is seeing the rise of left-wing Democrat Bernie Sanders with declarations like this one (in Los Angeles on 21 December):

“Our campaign is not only about defeating Trump, our campaign is about a political revolution. It is about transforming this country, it is about creating a government and an economy that works for all people and not just the 1%.”

I am highlighting this because it is a remarkable statement. It marks the distance we’ve covered in a single decade: This is the language of the Occupy Wall Street movement that opened the decade in 2011. And now the once derided concept of the 1% against the 99% has gone mainstream. So much so that it can buoy a candidate in his bid for the White House (Sanders, as I write, is just behind Biden and ahead of Warren).

You see rants in headlines, like this one from C-Net’ s Jackson Ryan: “We see the effects of climate change and our leaders continue to ignore the science”. A rant coming not just from journalists but scientists too.

Now, in 2019, we can all agree that the “world is on fire” and that the 2010s have been a “lost decade”. Yet back in 2013, K.C. Green, a talented cartoonist could still joke about it in a stunning piece of black humor. This is the closing panel of his 6-panel piece:

It’s no longer a joke. It really looks like we are headed for a burning world in which the last fossil fuel billionaire stokes the fire, cackling madly.

The “Bad Billionaires”: Corporate Support for Climate Change Deniers

How did we get there? Simple: It is in the interest of our leaders to deny climate change. In the U.S., politicians – most Republicans, some Democrats too – are at the beck and call of fossil industry lobbyists. Their campaigns are financed by right-wing donors. Since the 2010 US Supreme Court decision of Citizens United vs. Fec , limits on electoral spending have been effectively rolled back and the door is opened to unlimited corporate funding.

Money speaks and the power of money has never been so great in the United States.

Consider the Super Pacs (Political Action Committees) allowed to raise unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals, then spend unlimited sums to overtly advocate for or against political candidates. Unlike traditional PACs, super PACs are prohibited from donating money directly to political candidates, and their spending must not be coordinated with that of the candidates they benefit.

Don’t be fooled, that’s a minor inconvenience. As of December 26, 2019, 1,654 groups organized as Super PACs have reported total receipts of $182 million – getting ready for the 2020 presidential campaign.

Among them, FreedomWorks which is associated with the Tea Party and is also a member of the Koch brothers-founded State Policy Network, a national network of free-market oriented think tanks. Classified as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, it is funded by donations from mostly right-wing foundations (e.g. Lovett and Ruth Peters Foundation backing charter schools, the Castle Rock Foundation and the Bradley Foundation supporting the free market and limited government). Plus a range of corporate donors, including the Koch brothers, Philip Morris, Kraft Foods, GlaxoSmithKline, Facebook, Microsoft, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, and Comcast.

Yes, the link is there for all to see: The Kochs are among the world’s most infamous billionaires whose wealth is based on fossil fuels. And they are very, very active politically.

But there are also some encouraging counter-trends and the outcome is uncertain. We could still come out of it, with some burns but alive and kicking.

The Push Back: Climate Deniers in a Corner

Take a look at the facts. The decade opened with Occupy Wall Street and is closing with Greta Thunberg’s Friday Climate Strikes. Thunberg, along with the UK’s Extinction Rebellion going global and the Sunrise Movement spreading across the whole United States has placed climate change as the #1 issue on the global agenda.

For the first time in fifty years, since awareness of climate change and the threat of civilizational collapse emerged in the 1960s-70s, climate deniers are put in a corner. Hope is rising that the political landscape might finally shift and something will get done. Greta Thunberg was in fact named Time Person of the Year.

If we lived in fair and thriving democracies, Greta Thunberg’s cry for the climate would be heard and she would succeed in changing policy, no doubt about it.

But what can we expect from a world led by billionaires? Over the decade, their numbers have been rising fast and so has their influence, especially in the United States.

The 2010s’ Explosive Rise in Billionaires

The number of billionaires more than doubled over the decade and their control over world wealth almost tripled. Stunning.

In 2010, billionaires numbered 1,011 with a combined wealth of US$ 3.6 trillion. Today they are close 2,754 with a combined wealth of some $8.7 trillion, about 12% of global wealth. (according to the Wealth X Billionaire Census 2019).

America stands out with 705 billionaires, 25% of the total. China, next on the list, has only 285, and then comes Germany (146), Russia (102), and the United Kingdom (97).

Back in 2010, Mexico’s Carlos Slim was the wealthiest individual with a net worth of $ 53.5 billion. In 2019, it’s Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos, with $131 billion. Actually, he is a star, the first “centibillionaire” (over US$ 100 billion) in History. He reached the mark in 2018 with a reported net worth of $112 billion (according to Forbes).

Two facts are striking when looking at the top ten billionaires in 2019 compared to 2010:

- they are now mostly American and,

- on average, they are much younger.

These differences are not just limited to the top ten.

For the first time, in 2019, a 21-year-old (American of course) is included in the list: Kylie Jenner of Kardashian fame and founder of Kylie Cosmetics. That makes her, for now, the youngest billionaire in the world. She is a successful model (like her sisters) and no doubt an excellent manager, but her access to the Forbes billionaire list was secured when her products went viral online.

That alone – online virality – is indeed a major feature of most new billionaires: They tend to happen in the ICT industry (and finance too), and no more so than in the United States. American entrepreneurs were the first to leverage the power of the Internet. It should come as no surprise that San Francisco, significantly close to Silicon Valley, has more billionaires per inhabitant than any other top city – ahead of New York, Dubai, and Hong Kong.

Billionaires: How They are Linked to the 2010s Major Trends

The main trends that shaped the 2010s are closely linked to the rise of billionaires. A link, of course, is not necessarily a causation. But looking at the trends more closely reveals that there may very well be a causation, and a worrisome one too.

Incidentally, I don’t think that anyone can dispute that these are the major trends shaping the politics of the 2010s: rising income inequality, a decline in democracy and the rise of populism.

Trend #1: Rising Income Inequality

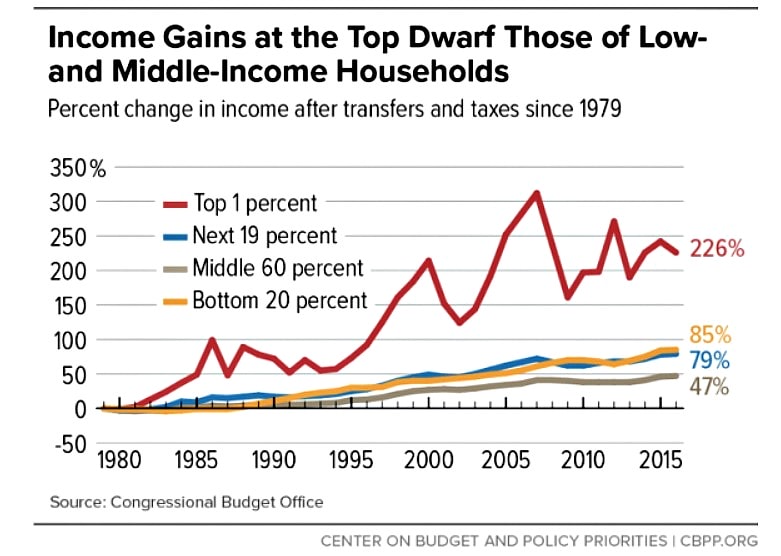

Here the link and causation are evident. When the one percent in America owns as much as 40% of the country’s wealth, the highest share it’s ever been since 1962, it is obvious that the two phenomena go hand in hand. The world’s richest one percent, defined as those with more than $1 million, own 45 percent of the world’s wealth.

Oxfam’s yearly report on inequality has become famous by now as it has featured shocking numbers showing how unequal the world has become and how fast it’s happening, like a tsunami: by 2017, 42 billionaires had as much as the bottom 50%. By 2018, just 26 billionaires had as much as the bottom 50%, i.e. 3.8 billion people.

The OECD, the world’s club of the richest countries, tells the same story. According to OECD data, income inequality in OECD countries is at its highest level for the past half-century. The average income of the richest 10% of the population is about nine times that of the poorest 10% across the OECD, up from seven times 25 years ago.

Of all OECD members, income inequality was the greatest in America (CBPP.org data):

The correlation with the high number of billionaires is obvious: America has the world’s greatest share of billionaires (25% of the total) and added more of them in the 2010s than did any other country:

- America went from 404 to 705 over the decade, adding 301 billionaires to its tally;

- China, next down the list, with the fastest-growing group of billionaires, went from 89 to 324, adding 235 billionaires.

Two factors encouraged the continuous creation of American billionaires over the decade:

- US-led globalization that permitted unrestricted outsourcing to low-wage countries and thus the accumulation of extraordinary cash piles, as exemplified by Apple, notoriously reliant on Foxconn in China for the manufacture of its products;

- the free market ideology, an ideology that reigned supreme in the U.S. – more than anywhere else, swiping government regulations away. It also encouraged American corporate creativity in devising tax avoidance strategies. Amazon, Google, Apple and the other digital giants took systematic refuge in low or no-tax havens, from Ireland to Luxembourg, from Delaware to the Cayman Islands, effectively protecting their profits.

By 2016, with Trump’s victory, a billionaire walked in the White House for the first time. And he promptly formed the most billionaire-packed cabinet in History. This is a fact that fits neatly into the next two major trends of the decade, the decline in democracy and the rise of populism.

Before we look at them, note that we are not discussing here reductions in the number of people in absolute poverty. No one disputes that there has been considerable improvement over time. Worldwide, the drop in the percentage of people in extreme poverty (defined by the UN as living on less than $2 a day) is remarkable:

Before we pat ourselves on our backs as Nicholas Kristof just did in the New York Times (This Has Been the Best Year Ever), we have to remember that this has nothing to do with rising income inequality. Both – inequality and extreme poverty reduction – are happening together and for entirely different reasons.

The reduction in extreme poverty is largely a result of effective government welfare programs around the world. Even in the United States that is not particularly socially-minded, Federal economic security programs cut poverty nearly in half over the last 50 years. Note also that the above graph stops in 2015. Thus, in the U.S., Trump’s cut back on such programs (which directly hurt the American poor) is not included.

Also, there’s no denying that global philanthropy and foreign aid have been major factors in reducing extreme poverty.

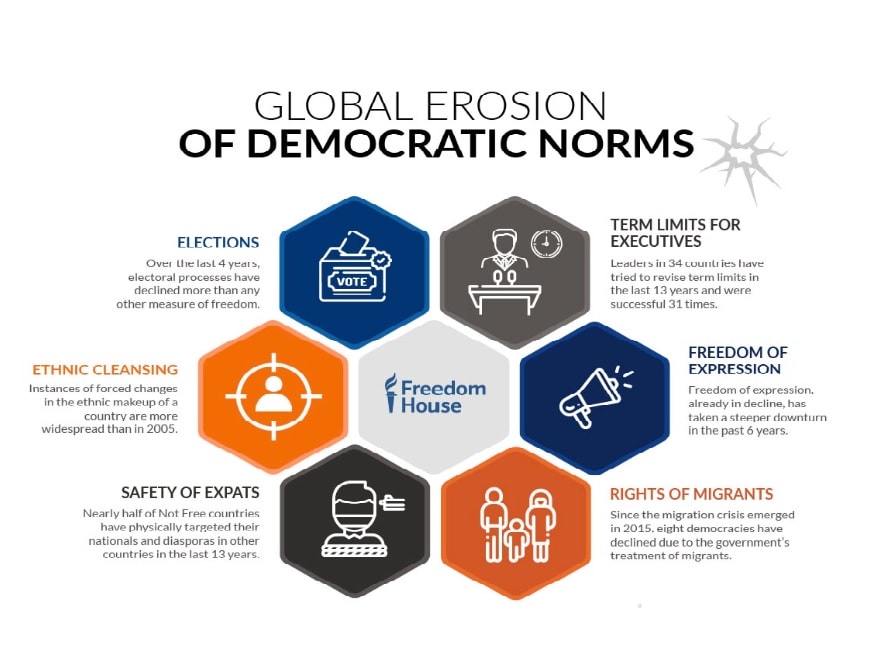

Trend # 2: Decline of Democracy

Freedom House data is loud and clear on this question. Democracy is in retreat around the world since 2008. In the decade after the end of the Cold War, it had flourished like never before. No more. The 2010s saw a continuing erosion of democracy, even if some countries fared a little better in 2018 than 2017 (Malaysia, Ethiopia, Angola, Armenia).

The swerve to what Hungary’s Orban proudly calls “illiberal democracy” is continuing – where major freedom-guaranteeing institutions like an independent media and justice system are either weakened or no longer exist.

Larry Diamond, a leading American scholar who has dedicated his life to studying democracy, has repeatedly argued, along with a score of other eminent researchers, that the decline of democratic institutions is accelerated by the rise of income inequality. An elite’s interests simply do not coincide with society’s as a whole. Democracy works best in a more egalitarian society.

In his latest book, Ill Winds: Saving Democracy from Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition, and American Complacency (June 2019), he surveys the American situation, finding several shortcomings, notably in the Republican party gerrymandering and the 2010 Supreme Court United Citizens decision that opened the door to corporate meddling in elections. The link here with the rise of billionaires couldn’t be clearer.

Trend #3: Rise of Populism

The 2010s saw the rise of populism across the world, from Duterte in the Philippines to Erdogan in Turkey and Bolsonaro in Brazil. Eastern Europe and Austria literally fell in the hands of populists, while they continued to gain ground across Western Europe throughout the decade, notably Marine Le Pen in France, Salvini in Italy and the Alternative fur Deutschland leaders in Germany.

Populism, as I have reported in an article reviewing German scholar Jan-Werner Müller’s excellent book What is Populism? (2016), is dangerous for democracy. It exploits people’s fears of immigrants, of being left behind by globalization and promises a return to protectionist nationalism. The promises are never kept but no matter, the votes pour in nevertheless.

Populism, in short, is an extraordinarily effective political tool for winning elections. The success of Brexit owes a lot to populist empty promises of “regaining control” of the nation. In fact, the UK, far from gaining control, is now risking breakup: a possible return of Irish violence, another Scottish referendum for independence. There is even a theory (unconfirmed) that Brexit has been supported by financial interests aiming to turn the City of London in a deregulated light-tax Singapore-on-Thames across from Europe.

The link with billionaires is nowhere more obvious than in the United States and in Trump’s 2016 victory.

Counter-trends: The rise in (Good) Philanthropy and the Breakdown of the Free Market Ideology

Climate activists like Greta Thunberg and the Extinction Rebellion or Sunrise are not alone. In the 2010s, two facts changed the game for them:

- A growing number of billionaires see beyond their self-interest and sincerely worry about the planet; they are often among the top 100. Foremost among them, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Michael Bloomberg, George Soros. These are people who pursue social justice and environmental goals, mainly through their philanthropies.

- The neoliberal free-market ideology, unchallenged since the fall of the Wall of Berlin to the extent that it was dubbed “the Washington Consensus”, is finally coming to an end, at the hands of a wave of brilliant “renegade economists”.

When a Billionaire’s hobby turns political

Philanthropy has always been a billionaire’s hobby, often his passion. In August 2010, the Giving Pledge was created by Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett, with 40 of America’s wealthiest joining together in a commitment to give the majority of their wealth to address some of society’s most pressing problems – ranging broadly from poverty, refugees, health, education, gender, justice, environmental sustainability to arts and culture.

In 2013, the Pledge went global and today includes more than 200 billionaires from 23 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China (mainland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong), Cyprus, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Monaco, Norway, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, South Africa, Switzerland, Tanzania, Turkey, Ukraine, UAE, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Watch Bill Gates tell us about climate change and what needs to be done (video filmed in February 2019):

Who can disagree with him? The new mega-donors are shaping the social agenda not only in the U.S. but around the world.

Over the 2010s, it has become a new form of American soft power. And an arena for political battles. Because billionaires cover the whole political spectrum from left to right.

David Callahan, in his book The Givers: Wealth, Power and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age (2017) presents Bloomberg as an iconic model of the new kind of “activist philanthropist”. He may have spent $250 million on his political campaigns to win three terms as mayor, but he has spent several times more than that on charity. And on fighting climate change – for example, giving $130 million to the Sierra Club plan to help shut down coal plants, thus saving an estimated 5,500 lives annually in recent years.

On the political spectrum, Bloomberg stands somewhere in the middle. Soros is far to his left (scaring conservatives) and the Koch brothers far to his right (scaring progressives).

Callahan makes the case that the wealthy have a different set of ideas and values than the general public: They are “more fiscally conservative and socially liberal than the population as a whole. They have a stronger belief in market solutions and technocratic fixes, and don’t share the public’s rising concern that the system is ‘rigged’.”

Indeed. Populism which thrives on exploiting precisely that concern (the system is “rigged”) does not scare billionaires. Those on the right see populism as a convenient means to gain political power; those on the left stay away (Soros has literally retired from active political involvement). In fact, Chavez, Venezuela’s populist leader, and his successor Maduro have destroyed their country and in the process, given a very bad press to left-wing socialist populists.

A shift in ideology: From the Free Market Neo-Liberal Ideology (dead) to…Institutionalism?

Politicians need slogans to be effective. And that has been historically the job of economists: Provide the ideas that underpin policies.

The 2010s witnessed a vicious battle between neo-liberals a.k.a. free market ideologists and young rebels often tagged as “institutionalists, a misleading denomination – merely because they insist that there is no such thing as “free” markets, that markets are in fact always regulated and there’s no such thing as “free competition”. Economic life, de facto, takes place in the shade of a society’s institutions, customs, and traditions. All “institutional” factors that need to be taken into consideration to devise effective policies.

Perhaps the most famous book by an “institutionalist” was 23 Things They Don’t Tell you about Capitalism by South Korean economist Ha-Joon Chang, a Cambridge University professor published in 2011. A neat, easy-to-read 23-point rebuttal of neo-liberal tenets which he demonstrated as having been the cause of the 2008 Recession. It was a loud firing shot at the free-market ideology and an instant bestseller.

But he wasn’t alone. On his heels, two brilliant women published books in the decade that shook the foundations of economic science:

- Italo-American Mariana Mazzucato, author of the Entrepreneurial State (2013) highlighting the foundational role of government in basic research and in stimulating innovation, as shown notably by the Internet, a federal DARPA-funded invention – yes, technological progress is not just the result of the “free market”; and the Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy (2018) that redefines the production boundaries so that value creation can be clearly distinguished from value extraction (not the case in neoliberal economics);

- British Kate Raworth, defining herself as a “renegade economist”, is the author of the groundbreaking Doughnut Economy (2017) arguing that endless economic growth as advocated by neo-liberal economists makes no sense in a world of finite resources and that an entirely new economic model is needed:

The coming changes in economics may sound highly technical but they won’t stay long up there in the cloud. They will come down to affect our politics (and politicians) and ultimately have a profound impact on our various societies in the coming decades.

For starts, expect the very concept of Gross Domestic Product to undergo fundamental change over the coming decade. Major economists have been working on this issue for some time now, notably Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel laureate and Columbia University professor. He is making waves with his latest book, Measuring What Counts: The Global Movement for Well-Being, a “bold agenda for a better way to assess societal well-being” (2019) co-authored with French economist Jean-Paul Fitoussi and chief OECD statistician Martine Durand.

As Stiglitz explained:

“It’s time to retire metrics like GDP. They don’t measure everything that matters. The way we assess economic performance and social progress is fundamentally wrong, and the climate crisis has brought these concerns to the fore.”

Expect to hear a lot less about economic growth in the 2020s and a lot more about sustainable social progress. It will be a question of re-arranging and redistributing our resources (not growing them) within the “doughnut”’s “safe and just space”.

Perhaps even the word “development” will get dropped out of the SDGs.

What Next: Will the 2020s see the Battle of Billionaires?

With democracy in decline and populism on the rise, the stage for epic political battles is set. Which side will win? The better side, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Bloomberg et al. or the other side, Koch, Trump, Mercer, and the climate deniers?

We know the backdrop for this play: The climate crisis threatening our world as we know it. And barriers between humans that make it harder to address. The barriers that populist politicians exploit: xenophobia, racism, misogyny, homophobia, fear of exclusion, of falling behind – feelings that are channeled into fascism, “white supremacy” etc.

Who’s behind populists? We have to remember that in a deeply unequal world, behind every politician, there is a billionaire. And behind every politicized billionaire, there is an economist whispering his pet theories.

Conservative billionaires find solace in Milton Friedman’s ghost calling for maximizing shareholder value, Ayn Rand’s uncompromising, individualistic architect in The Fountainhead, and Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings in pursuit of power.

An aside regarding right-libertarians who are running away from the issues. Literally. Elon Musk wants to retire to Mars, Peter Thiele may have supported Trump but he has opted for New Zealand. Others are building themselves shelters against every kind of disaster. For example, the Survival Condo is a former nuclear missile vault in Kansas that has been converted into high-end residences. When the 12 apartments there were put on sale in 2011 starting at $1.5 million, all units sold within months.

Running away or hiding in the ground like an ostrich won’t solve the problems.

Progressive or middle-of-the-road billionaires are keenly aware that endless growth is no longer the answer. Simply because it’s no longer feasible. We are hitting the ceiling of the planet’s resources.

If everyone in the world was to live like an Australian, it would require the resources of…five Earths.

And barriers between humans need to be broken down. Even the conservative OECD Secretariat is pushing for breaking down barriers – for example, barriers to gender equality. , The impact of pay inequality is dramatic over a woman’s lifetime: On average, in OECD countries, women earn 16% less than men, and female top-earners are paid 21% less than their male counterparts. Women occupy less than a fifth of parliamentary seats around the world and their access to top positions in companies is even worse.

So the stage is set: The One Percent is split. Free-market, libertarian billionaires on one side, new “institutionalists” or societal billionaires on the other.

It is clear that the upcoming US presidential election will be key and will set the tone for the decade. Will Trump, the billionaire climate-denier win?

If Trump wins, the United States’s current loss of leadership will be confirmed while the damage to the environment of another four years of Trumpian misrule is incalculable. The problem is: Given the mega-size of the American economy, can the world recover in time to save itself from climate Armageddon?

Featured image: From left to right: Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, George Soros, Mark Zuckerberg