Updated Aug.14, 2022. The world breathed a sigh of relief when China concluded its fourth day of military exercises around Taiwan without incident despite the fact that, for the first time, the drills had been carried out with live ammunitions. And that meant that at any moment, the situation could have degenerated from war games to real war.

The next day news came that live-fire drills would continue in the southern waters of the Yellow Sea until mid-August as well as anti-submarine attacks and sea raid practices just off Taiwan. And that is likely to continue for a while, probably until this fall when Chinese leader Xi Jinping gets his third term confirmed.

So China is busy flexing its military muscle.

First impact of China’s drills: US-China relations cratered

US-China relations have nose-dived, with China’s foreign affairs ministry announcing that “following Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan”, it is halting dialogue on a range of issues, including climate talks, military dialogue, cooperation on crime as well as maritime safety mechanisms and relationships on immigration and anti-drug policies.

All observers – the Pentagon included – have deplored the timing of Pelosi’s visit, but it should be recognized that she simply reflected a long-standing American policy line: On one hand, the US follows the One China policy whereby it has formal ties with China; on the other, it rejects the “One China” principle, whereby Taiwan is an inalienable part of China to be reunified.

The US supports Taiwan’s independence and has always had “robust unofficial” relations with Taiwan, including continued arms sales, contributing to the island’s defense.

Europe’s relations with China are also taking a turn for the worse

It’s not just US-China relations that have suffered. Europe’s relations with China are becoming ever more strained even though China is its largest trading partner. EU Parliamentarians, far from being cowered by war drums are planning to follow Nancy Pelosi’s example.

The reasons? Aside from the fact that most visits were planned before Pelosi’s visit and that the most recent “EU summit” between the EU and China held by video on April 1 was concluded on a deeply negative note, there is the matter of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry which is vitally important for Europe.

As explained in a recent Politico article, Europe needs Taiwan: Last year, almost 60 percent of EU imports from Taiwan last year were machinery and appliances. European businesses depend on a continuing supply of electronic chips, produced by the world’s biggest semiconductor company: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) which is also known to have some major American clients, in particular Apple and Qualcomm.

Why China has become militaristic: Xi Jinping’s obsession with “national security”

In an insightful article published following these events, Chris Buckley, the New York Times Chief correspondent who has lived in China for the past 30 years and Steven Lee Myers who recently covered the coronavirus news in China attempted to explain the situation, arguing that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is out to build a “security fortress” for China and himself.

Ever since he came to power in 2012, they argue, Xi has considered with suspicion the so-called “color revolutions” – from the Czech Republic to Ukraine to the Arab Spring countries, carried out in the name of democracy – seeing them as a direct threat to the Chinese Communist party’s grip on power.

His solution, they say, was to focus on “national security”, both domestic and external. And they conclude, “As Mr. Xi prepares to claim a breakthrough third term as leader at a Communist Party congress this fall, he has signaled that national security will be even more of a focus.”

National security, both domestic and external, has thus been Xi’s focus from the start, and he was never soft-hearted: He notoriously authorized the mass incarceration of Uyghurs and abolished Hong Kong’s special free status that China had promised to leave in place for 50 years when it regained the territory from Britain in 1997.

More importantly, he created a new government organ to carry out his national security policies: The National Security Commission. While its size, staffing and powers are unknown, the goal is clear: In the name of heightened “vigilance”, screws are turned on personal freedoms and human rights. And the Commission is firmly in Xi’s hands, as he has established new rules and made personnel appointments.

By 2018, Xi declared himself satisfied, saying the commission had “solved many problems that we had long wanted to but couldn’t.”

The Commission established a network of local security committees across the whole country – at the province, city, and county level – with the objective to address domestic threats like protests and dissent but it didn’t stop there. It also set out to control the world of Chinese tech billionaires, ordering financial security assessments of banks.

And that gave results: Last month, Chinese regulators fined the ride-hailing giant, Didi Global, $1.2 billion for breaches, citing unspecified “serious” national security violations.

For Xi, national security is a “people’s war,” enlisting all Chinese citizens, not just the military but civilians, including elementary schoolteachers and neighborhood workers.

For example, on April 15 every year – a day that since 2015 has become National Security Education Day when it was established by law – children have lessons about dangers that include food poisoning and fires, but also spies and terrorists.

Or consider the Ministry of State Security’s recent offer of rewards of up to $15,000 for citizens who report information on so-called “security crimes”.

Last year, for the first time, a National Security Strategy was formulated, laying out broad goals through 2025 – not much is known about this document except for a summary issued when party leaders approved it. And that calls for making China’s economy more autonomous in key areas like food and technology and, ominously, for finding methods to prevent social unrest.

The risk is that Xi is creating with such policies a climate of deep distrust that can affect not only normal citizens’ lives and limit everyone’s freedoms in China but cloud international relations.

And this year, the focus has indeed turned on perceived external threats: In a new 150-page “textbook” on Mr. Xi’s “comprehensive outlook on national security”, we read that China must “deepen its partnership with Russia to withstand international threats”.

In short, for Xi’s China, the West in general and the US, in particular, are the real enemy.

The threat: Will China be tempted to follow Putin’s example with Ukraine and reclaim Taiwan?

The threat is real, China has always considered Taiwan a province of China and sees the government of Tapei as insurrectionist and separatist, refusing to rule out the use of force to bring Taiwan back into China’s fold.

Until October 1971, the Taipei government held the Chinese seat at the UN when it was voted out and replaced by Beijing. Now, Taiwan has diplomatic relations with only 14 out of 193 UN member states (including the Holy See) – this is a result of China pressuring its allies not to recognize it.

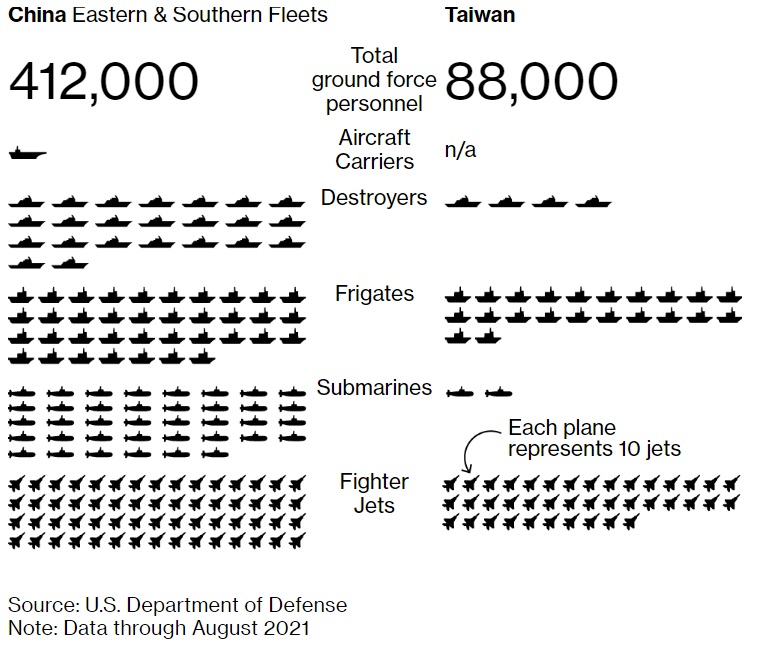

And there is the problem of size: Taiwan, compared to China, is tiny in every way – small territory, a population of 24 million vs. 1.4 billion, and only a total of 169,000 active troops compared to some 2.7 million enlisted soldiers in China (2018 data).

From a military standpoint, Taiwan is David against China’s Goliath.

Beijing massively outguns Taiwan, with estimates from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute showing that China spends about 25 times more on its military. And here is the US Department of Defense’s estimate of the forces facing each other (2021 data):

But Taiwan, even compared to China, is a big player in the global tech sector, thanks to flourishing semiconductor and electronics industries; major export trading partners are China (including Hong Kong), the United States, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia, and Germany. But, what is notable, is that China is by far Taiwan’s main trading partner, far bigger than the US and Taiwan’s most important chip factory is located in China, run by industry leader Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSM).

In short, Taiwan is the chipmaking factory of the world, producing over 50% of the chips the world uses; it clearly has a key role in supplying everyone with cutting-edge technology devices, from laptops to automobiles to advanced weapons.

Alas, a country’s economic pre-eminence has never shielded it from the possibility of war. And so, setting aside the humongous human toll of war, what would Chinese aggression on Taiwan look like?

And an even more pressing question: Would America be directly involved or would it choose to stand by, the way it has done in Ukraine, limiting itself to the provision of military equipment and arms and applying sanctions?

China-Taiwan war: Would America intervene? China could be tempted to follow Russia’s example in Ukraine

Most likely, the war would start with Chinese missiles directly striking Taiwan and US bases throughout the Western Pacific. Perhaps at first China would try to avoid hitting American targets, yet America cannot afford to stand by and watch Taiwan being smothered.

Taiwan is not Ukraine.

First, because Taiwan has a defense pact with the US dating back to the 1954 Sino-American Mutual Defence Treaty, meaning the US could be drawn into the conflict. Ukraine never had such a treaty protecting it and wasn’t part of NATO.

Second, Taiwan is a democracy like Ukraine, so the theory goes, it would politically behoove the US to come to their defense since the US sees itself as a champion for democracy.

But the way it will defend them must necessarily be different: Taiwan’s situation is not comparable to Ukraine’s.

There are several reasons for this difference.

One, Ukraine, large as it is and able to mobilize a great number of its citizens, has a real possibility of winning the war if adequately armed and sufficiently severe sanctions are slapped on the aggressor – which is something the US (and its allies) are actively engaged in doing.

Ukraine, with adequate help from the West, can hope to push back the Russian invasion and maintain its identity.

For small Taiwan, the possibility of push-back does not exist – even though it has a rugged coastline and rough seas appropriate for guerilla-type warfare (but this would only prolong the struggle, it would not likely lead to victory). Also sophisticated cyber warfare would no doubt be part of it and it might not necessarily work in favor of Taiwan, on the contrary.

Bloomberg reports that China would use cyber and electronic warfare units to target Taiwan’s financial system and key infrastructure, as well as US satellites to reduce notice of impending ballistic missiles. And “airstrikes would quickly aim to kill Taiwan’s top political and military leaders, while also immobilising local defences”.

And this would be followed by an actual invasion with “thousands of paratroopers […] looking to penetrate defences [and] capture strategic buildings.” Taiwan’s top military, still according to Bloomberg, are currently busy devising “a multi-pronged” response to such an invasion.

A grim picture.

So, in the case of Chinese aggression, the spectacle of a crushed Taiwan would make it difficult for the US not to intervene.

But there is another good reason why the US would have to react directly and not limit itself to sanctions and provision of arms: Taiwan, thanks to its electronics industry, plays a crucial role in the world economy and particularly in the US economy that rebounded in the 21st century precisely thanks to Silicon Valley and the digital revolution.

Taiwan is inextricably linked to the US, with an economic activity that sits at the very heart of America. That was never the case with either Ukraine or Russia whose main exports – grain and fossil fuels – do not have such strategic importance to the US.

Therefore, US direct involvement is inevitable. And Xi Jiping should take note and not believe that he can follow Putin’s example, betting that the US would simply slap on sanctions and provide arms.

Such a bet would have fatal consequences.

Expect the war to be long and intense, with protracted struggles for control of the air and sea that would make shipping lanes in that part of the world impassable. And that would affect about one-third of the world’s seaborne traffic.

In a globalized world increasingly dependent on sea trade, the economic shockwaves this war would create are simply going to be enormous. As Hal Brands writes in a Bloomberg article about the possibilities of such a war, “the destruction of critical plants and the interruption of shipments would constitute a global economic emergency” of unthinkable proportions.

Much worse than the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Because comparison with the war in Ukraine is on everyone’s mind and as Hal Brands puts it, “A war over Taiwan would not be a conflict between two lackluster economies, as with Russia and Ukraine. Assuming the US intervened, it would be a brawl involving the two largest economies in the world — perhaps the three largest, if Japan fought in support of Washington and Taipei.”

Actually, such a war would not likely stop with Japan: With the recent signing of AUKUS, a treaty linking the US with Australia and the UK, it is very likely to also quickly involve those two countries – even if this has become a subject of debate in the UK as shown by the recent spat between Boris Johnson and Theresa May.

More broadly, considering the importance of German-Taiwan trade and the numerous links between the EU and its member states with the US, it is difficult to see how Europe could avoid participating in such a war, particularly if it turns out to be a protracted one.

In short, a world war. And one that would likely see the US navy blocking the Malacca Straits early in the conflict, hitting China where it would hurt the most, cutting off its energy supplies, the oil and gas it imports from the Middle East and that is crucial to make its economy run:

Another cause for worry: America’s military advantage over China may not last

Some years ago, in 2015, a RAND Corporation study found that a China-US war lasting one year would slash America’s gross domestic product by a whopping 5% to 10%. But it would cut China’s gross domestic product by a catastrophic 25% to 35%.

That picture of an American advantage in a China-US war is one that most experts appear to agree on – although, more recently, there are concerns that the gap is narrowing and that China’s chances are improving.

That is the case made by Admiral James Stavridis, a retired Allied Commander of NATO and Dean of the Fletcher School of Diplomacy at Tufts University, who has spent the bulk of his operational career in the Pacific.

In a striking article published last year (May 30, 2021) in Nikkei Asia, he argues that overall, in terms of military resources, the US advantage “is not as overwhelming as it appears.” That’s because, in terms of simple numbers of warships, China is already leading the U.S., roughly 350 to 300, in combat vessels. However, U.S. ships are still “ton-for-ton larger, endowed with better offensive and defensive systems, and manned by far more experienced crews.”

In short, “factoring in the tight geography of east Asia, I would say slight advantage China in terms of pure numbers of platforms both sea and air, with the U.S. having higher quality of assets.” (bolding added) And he notes: “ the string of artificial islands built by China throughout the South China Sea would somewhat balance the U.S. bases in South Korea, Japan and Guam.

This view was recently confirmed by Admiral Pierre Valadier, head of the French navy, who said, according to Politico, on July 27, a few days before China carried out its military drills around Taiwan:

“I have spent the last two years explaining everywhere that we are witnessing a movement of naval rearmament unprecedented since the Second World War. In 2030, the tonnage of the Chinese navy will be 2.5 times greater than that of the American navy which, despite its efforts, will remain stable or even continue to shrink, while the Chinese fleet will be growing geometrically.” (bolding added)

But it’s not just a question of firepower – it’s also a question of alliances, and, as Stavridis points out, for a long time the US has felt it had the advantage over China with its worldwide network of allies – but, he notes, “China is increasingly taking a page from the U.S. and strengthening its systems of partnerships. The Belt and Road Initiative is designed to do exactly that.” (bolding added)

Lately, experts have worried about something else: That in case of war, China could get hold of the Taiwanese TSM’s digital facilities and workforce currently present on its soil, thus obtaining a major technological advantage. However, even this would most probably be a short-lived one as the US would be certain to make decisive (and destructive) countermoves.

So are we headed for World War III? This is truly an unthinkable outcome. Yet that is precisely the message in 2034: A Novel of the Next World War (published in March 2021) written by Admiral Stavridis with Elliot Ackerman, “a chillingly authentic geopolitical thriller that imagines a naval clash between the US and China in the South China Sea in 2034—and the path from there to a nightmarish global conflagration.”

The Wall Street Journal, in a glowing review of the novel, notes: “2034 is nonetheless full of warnings. Foremost is that war with China would be folly, with no foreseeable outcome and disaster for all.” As to Adm. Stavridis, he wryly observed that he set the novel in 2034, because that was, in his view, the most likely time when the military gap would close and “favor China if the US does not respond”.

Perhaps, we still have some 10 to 15 years left – hopefully, a solution will be found before America feels forced to strike back directly and Europe follows suit.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Taiwanese President Official Photo Credit: Wang Yu Ching/Office of the President.