Energy, whether it be in regard to poverty or transition, is essential to human life and society, naturally putting it at the forefront of the news.

The United Nations launched the Sustainable Energy for All initiative in 2012 (SE4 all); in 2015, SDG 7 was adopted, which is based upon “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy services at an affordable cost for all.” But energy is a broad notion: human or animal energy? Thermal power, mechanical or electrical energy? Energy to cultivate, cook, heat, pump, grind, cool, transport, move, build, light, ventilate, or communicate?

This article is focused on two crucial issues for those living in the most impoverished nations: traditional cooking practices and electricity. Furthermore, we will see how an NGO, GERES, is implementing concrete actions to address such issues.

Traditional cooking practices

When we discuss energy transition, we often imagine automobiles, electric power, and construction, but we rarely consider what goes on in the kitchen. In 2016, 2.74 billion people (worldwide) relied on the burning of biomass (wood, charcoal, vegetable waste, scrub, dried dung, etc) or — less often — on kerosene to cook on what have traditionally been inefficient and potentially hazardous stoves.

With the growth of the overall population, this figure has increased by more than 200 million since 2003, despite the fact that between 2000 and 2017 the share of the population concerned decreased from 61% to 46% of the overall population of developing nations. For example, an estimate revealed that approximately 81% of Sub-Saharan Africans, 33% of Chinese, 63% of Indians, and 14% of South Americans do not yet have access to clean cooking solutions.

The combustion of biomass is imperfect in three-stone fires, especially in regard to energy waste and toxic smoke emissions, including particulate matter and gases. Daily exposure to toxic smoke can cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and ocular disease in women and young children. It can also cause low birth weight in newborn children.

According to WHO, this leads to more than 4 million premature deaths per year, which is more than the annual number of deaths caused by malaria. In addition to these health impacts, there is also the physical demand of collecting such fuels, which often prevents young girls from pursuing an education.

Despite such disadvantages, biomass is unlikely to disappear. It is the most readily — if not only — accessible fuel for many low-income individuals, and it can be easily adapted to local cooking practices. Ironically, cooking with LPG or electricity can actually be less expensive than biomass — depending on the context, naturally — but individuals can often not afford the upfront cost of a cylinder nor that of the refill. They can, however, afford to pay for their daily use of biomass fuel.

Another advantage of biomass is its widespread availability in local markets. Its prices are also less subject to fluctuations in world markets than fossil fuels, although in some countries like Cambodia, the growing scarcity of biomass can make the price of wood-fuel more unstable. Moreover, there is a whole range of activities and therefore jobs around the production, transportation and distribution of wood and charcoal, which can make it – under certain conditions – a contributor to sustainable and local economic development.

Yet, burning biomass on inefficient cooking appliances still leads to environmental pollution. Wood, for example, is a renewable energy and a means of carbon storage, but over-exploitation of the forests, due to agriculture and industry, combined with inefficient combustion contribute to the depletion of resources and overall forest degradation.

Furthermore, this can result in an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, namely carbon. If the extraction of timber exceeds the growth of trees, meaning if a resource is over-exploited without having the opportunity to replenish itself, more carbon will be emitted by combustion than be stored by means of forest replenishment. It is predominantly in Central Asia (Afghanistan and Tajikistan), in South Asia (India and Bangladesh) and in East Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi) that the situation has degenerated the most: the mismanagement of firewood, coupled with the demographic growth, suggests an increase in the unsustainable extraction of such.

Luckily, solutions exist, such as improving the production efficiency of charcoal and the energy efficiency of cooking appliances, replacing wood with plant residues (rice husks, olive stones, etc), replanting with agroforestry methods, and exploiting the trees without destroying them.

In the photo: Improved Tandoor with a Cap in Afghanistan. Photo Credit: GERES.

In regard to cooking appliances, the Clean Cooking Alliance has worked with a global network of partners since 2010 in order to make clean cooking more accessible to families around the world. “The alliance supports the development, sale, distribution, and consumption of clean cooking solutions by the environment, creating jobs, and helping consumers save time and money.”

The following will address the subject of accessibility of electricity worldwide, as well as how GERES plans on tackling this issue.

Electricity, otherwise known as modern energy

In 2017, for the first time in history, the number of those without access to electricity dropped below one billion worldwide. Significant progress has been made, but “around three-quarters of the 550 million people who have gained access since 2011 are concentrated in Asia.” (IEA) The International Energy Agency forecasts that more than 700 million people will live without electricity in 2040, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

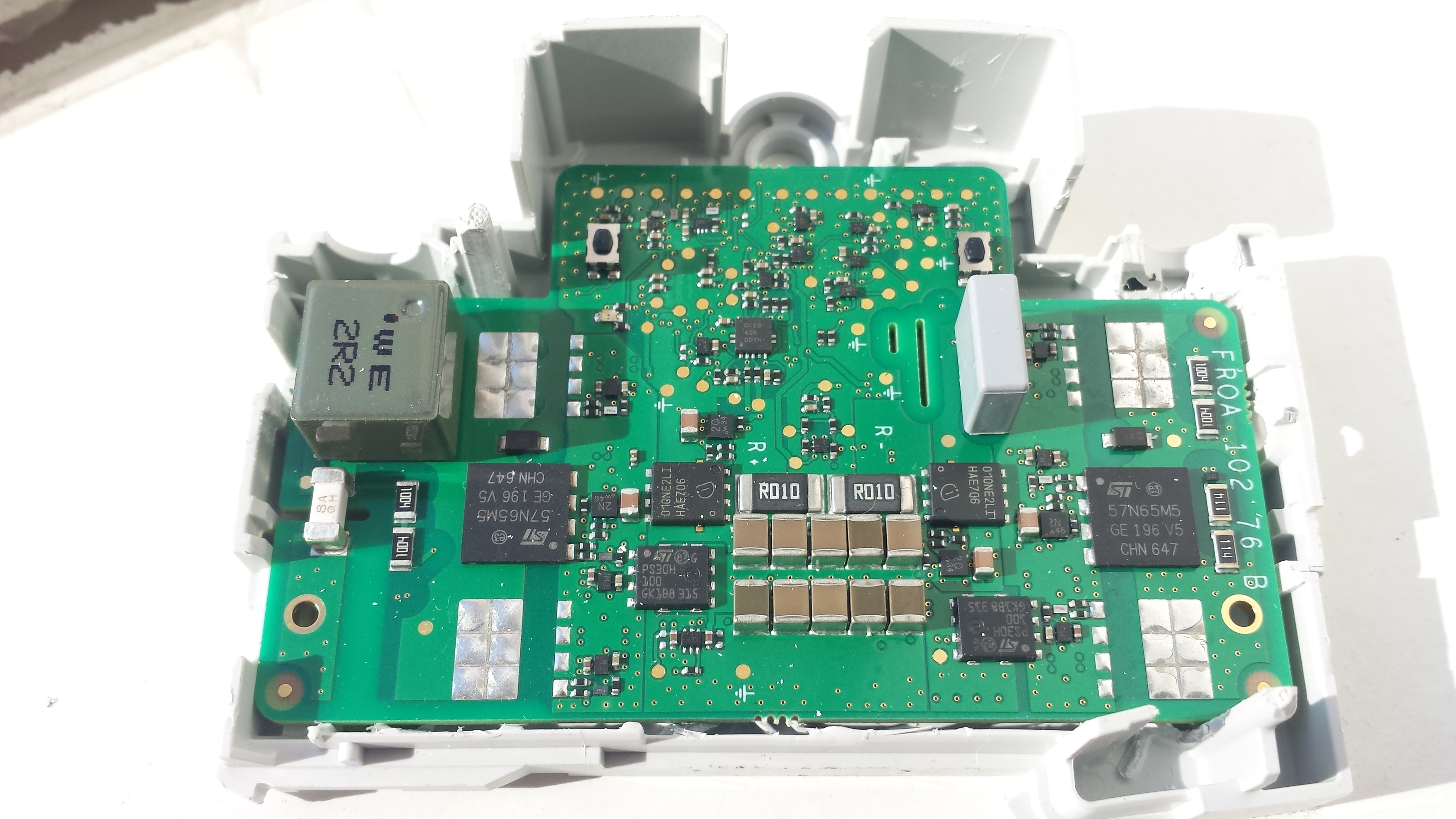

In the Photo: Managing Electricity in the Green Business Area of Konseguela, Mali. Photo Credit: GERES / Fototala King Massassy.

In Sub-Saharan Africa today, two-thirds of urban households —but rarely the most vulnerable — have access to electricity while only 19% of rural households have said access.

This data is incomplete, however, as it does not take into account the “spontaneous” one-off occasions of electrification provided by generators, solar lamps or photo-voltaic panels.

Supply cuts are numerous or they are mitigated by polluting generators, while solar kits provide limited power (often a few hundred watts), compared to the power offered by national power grids that mainly cover cities.

The low electrification rate and unreliable power naturally have a significant impact on businesses and household economic activities. Nearly half of African enterprises don’t have access to a source of electricity that is reliable enough to allow their business to grow and expand.

So, how can we speed up electrification without relying on power plants, which use high CO2 emitters, including coal (the least expensive solution), oil or gas?

This is where solar energy comes in, with its potential being most clearly demonstrated in developing countries. For example, the measurement of solar energy in West Africa ranges from 5 to 6 kWh/m2/day compared to only 3 kWh/m2/day in the European temperate zone.

In the Photo: Solar Panel in the Green Business Area of Koury, Mali. Photo Credit: GERES / Fototala King Massassy.

Wind energy is also present on some coastlines and landforms (Morocco, Southern Africa, Horn of Africa, Argentina, Chile, etc). One of the difficulties in these countries, however, is the lack of wind measurements, which prevents us from knowing the true energy potential.

In addition, some countries have geothermal resources (Kenya, Ethiopia, Central America, Philippines, etc) or, more often, hydraulic resources (Brazil, Central Africa, India, Southeast Asia, etc), but global warming (water flow reduction), negative impacts of mega dams (ecosystem destruction, land grabbing, etc) and competition for water between different users (agriculture, industry, cities, and electricity) threaten these resources.

Luckily, the development of renewable energy sources and their decreasing costs currently supports the growth of more ecological resources rather than the continued use of fossil fuels. Faced with economic and social uncertainty, as well as strong political pressure from the population, many development aid agencies, businesses — from start-ups to major global energy corporations — and NGOs such as GERES, have pledged their commitment to accelerating the process of electrification worldwide.

Shared solutions to produce and make better use of energy

GERES, a French NGO established in 1976, promotes innovative and suitable solutions to improve access to energy, further develop renewables resources, and assist vulnerable populations in the adaptation to climate change. The NGO operates in Sub-Saharan Africa (Benin, Mali, Senegal), Asia (Afghanistan, Cambodia, Myanmar, Mongolia, Tajikistan), as well as in the Mediterranean area (southern France, Morocco, Tunisia). In 2017, 64 projects directly benefited 164,600 people, including 4,776 small businesses.

In the Photo: Greenhouse in the Arkhangai Region of Mongolia. Photo Credit: GERES.

In Cambodia, Myanmar and Mali, GERES disperses improved cooking stoves, which are based on traditional cooking practices. These small single-pot portable cooking stoves, made with terracotta and metal, consume less wood and charcoal than standard stoves. Traditional potters and distributors are now trained to manufacture and sell them. In Cambodia, more than 3.5 million of these improved stoves are used in half of the country’s households, while a craftsmen’s association continues to promote them.

Launched more than 15 years ago, this large-scale distribution scheme has been funded by the sale of carbon credits. GERES was the first French organization to offer citizens and companies the opportunity to voluntarily offset their carbon emissions by supporting this project. In total, significant results have been achieved throughout the years 2003-2013: more than 1.6 million tons of wood saved, more than 2.5 million tons of CO2 avoided, 550 jobs created, and a yearly value of 2 million USD added to Cambodia’s economy.

Today it is in Myanmar, a country in which 77% of people do not yet have access to clean cooking, that GERES supports potters and distributors of improved stoves. 60 small entrepreneurs, about half of them women, manufacture and sell more than 6,000 improved stoves per month in the Dry area and Pathein area. In order to improve energy use in Myanmar on a larger scale, access to carbon finance is being considered.

In the Photo: A Woman in Myanmar uses an Improved Cooking Stove. Photo Credit: GERES.

In Mali, only 15% of rural people have access to electricity. In the south of the country, 50 km from the city of Koutiala and the national grid, the Green Business Area (GBA) of Konseguela rents out workshops to 13 small businesses (bakeries, oil mills, tailors, communication networks, cafés, etc). The GBA is equipped with a mini-hybrid plant that generates more than 10 MWh of electricity per year, with the help of photo-voltaic panels (12.5 kWp) and a 16 kVA generator running on jatropha oil (jatropha seeds are produced by farmers of the area on non-productive land). Since 2015, 35 jobs have been created, 115 jobs consolidated and 64 tonnes of carbon dioxide (tCO2eq) avoided.

A second GBA is under construction and several others are in the process of being prepared with the aim of meeting the specific needs of small rural businesses in areas with little or no access to electricity.

In the Photo: Green Business Area of Konseguela, Mali. Photo Credit: Fototala King Massassy.

In the Photo: Solar Panels in the Green Business Area of Konseguela, Mali. Photo Credit: GERES / Fototala King Massassy.

In Morocco, GERES supports hammam (public baths) owners in their effort to improve the energy efficiency of their buildings, which are of high social utility but consume large amounts of wood (around 10,000 hammams consume 1 ton of wood per day on average). A range of seven technical solutions and a lending mechanism are proposed according to the investment capacities of each one: energy-efficient poly-fuel boilers, use of sustainable biomass, heated floors, solar preheating of water, insulation, etc. After completing seven renovations, the challenge then becomes how to determine the appropriate financial and organizational arrangements in order to scale up such businesses.

In the Photo: Traditional Hamman in Morocco. Photo Credit: GERES.

One last example of GERES’s activities takes place in the cold mountains of Central Asia, with the focus on saving energy in buildings. In Afghanistan, GERES offers bio-climatic solutions to urban housing in order to reduce heating costs and improve comfort during winter. In Kabul, more than fifty artisans are trained in the construction and sale of energy saving solutions (ESS) for houses, with more than 5,000 passive solar verandas being installed so far.

In the Photo: Building a Passive Solar Veranda in Afghanistan. Photo Credit: GERES.

The main objective of the NGO is now to strengthen the association of artisans in order to guarantee its autonomy, as well as ensure a market-based dispersal of energy saving solutions. Most recently, on the 30th of January, GERES won the Energy Globe World Award for 2018 (category: “Air”) for its actions taken towards the spreading of energy saving solutions in Bamiyan and Warvak provinces.

Energy at the heart of the SDGs

However, access to energy remains highly unequal on a global scale, both between countries and within countries. The different scenarios presented show that, beyond SDG 7, the introduction or development of energy-efficient, environmentally-friendly and context-specific energy solutions naturally contribute to the achievement of the other SDGs.

The implementation of access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy for all (SDG 7) requires moving away from a strict “energy” approach in order to establish links with other sustainable development goals. Access to energy is a factor in reducing poverty (SDG 1) and inequalities (SDG 10), improving health (SDG 3) and women’s economic empowerment (SDG 5); it also helps strengthen the economic potential of the poorest territories (SDG 8). The need for renewable resources requires individuals to take into account the management of natural resources (SDG 15), which helps to contribute to the fight against climate change (SDG 13). Therefore, the aim is not only focused on energy.

GERES offers energy solutions as both a vector of economic and social development, as well as an alternative to existing systems that are harmful to the environment. Energy, climate change and economic inequality are all interdependent; they challenge the structure of our society. In a global context where those who consume the least amount of energy are those who suffer the most from climate change, energy therefore raises questions about social justice, interconnectedness, and ultimately the topic of “climate solidarity“.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

Featured Image — In the Photo: Flour Production in the Green Business Area of Konseguela, Mali. Photo Credits: GERES / Fototala King Massassy.

Related Articles: “Sustainable Energy Can Power a Health Revolution” by Sarah Butler-Sloss.

“Contributing to SDG #7: Affordable and Clean Energy” by Sille Krukow.