The Way Forward for Impact Investors

Review of “Investing in the Sustainable Development Goals in Kenya – A Primer for Philanthropists and Other Social Investors” – pdf report (40 pages) produced by Dalberg – Foreword by S. Chatterjee, UN Resident Coordinator in Kenya

In September 2015, at the United Nations General Assembly, something remarkable happened: Following the biggest consultation process in the history of the United Nations – it lasted three years and reached over 7 million people through 83 national surveys – 193 nations agreed to carry through with Agenda 2030 and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The intention was commendable: To conquer poverty worldwide and usher in an age of eco-conscious equity by 2030.

A victory for human development and the planet? Not yet. Between a formal expression of intent from sovereign nations and actual on-the-ground operations, the gap can seem like an unbridgeable chasm.

A year later, efforts to bridge that chasm are taking shape. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has just published a first, highly practical guidebook to help impact investors and philanthropists contribute to achieving the SDGs.

Perhaps, it should come as no surprised that UNDP took the lead. After all, the agency is famous for innovative breakthroughs: With the introduction in 1990 of its Human Development Index for ranking countries’ development, it broke down economists’ reliance on Gross National Product (GNP) as a key measure of wealth. The HD Index works along three dimensions, measuring a “long and healthy life”, being “knowledgeable” and having a “decent standard of living”. Twenty-five years ago, this was a totally new approach for advancing human well-being, today it is largely reflected in one way or another in Agenda 2030.

For this brochure – essentially a guidebook drawing the road map for achieving the SDGs in Kenya – UNDP called on outside experts from a major consultancy firm, Dalberg, known for the quality of its work. The result is a clear and relatively short (40 pages) professional document, free and conveniently downloadable as a pdf, with a foreword from Mr. S. Chatterjee, UNDP Resident Representative and UN Resident Coordinator. This is a position that enables Mr. Chatterjee to ensure coordination between all 25 specialized UN agencies and entities present in Kenya, from FAO to WHO, in line with the continuing UN-wide effort to deliver aid as “One UN”, ensuring that there is full coherence between all the agencies and no duplication. In fact, Kenya, in 2010, had requested the UN development system to adopt the ‘Delivering as One’ approach in its country.

This has resulted, inter alia, in the establishment of an “SDG Philanthropy Platform” embedded within the United Nations Resident Coordinator’s office. The Platform, launched by UNDP, the Foundation Center and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors in 2014, is intended as a “multi-country enabler of collaboration between philanthropy, United Nations, governments and others.” Kenya is one of the first pilot countries for the Platform.

For now, UNDP has produced only one such investor guidebook, but no doubt it plans to build on that approach and use it as a model to be replicated for other countries engaged in the SDG process. The idea behind this “primer” for impact investors is explained in the foreword: The intent is to enable them to “better understand and engage in the emerging framework of SDG delivery across priority areas in Kenya, with a special section highlighting the country’s education sector.”

In short, the specific audience for the book are philanthropic organizations and social investors.

Why Focus on Philanthropists?

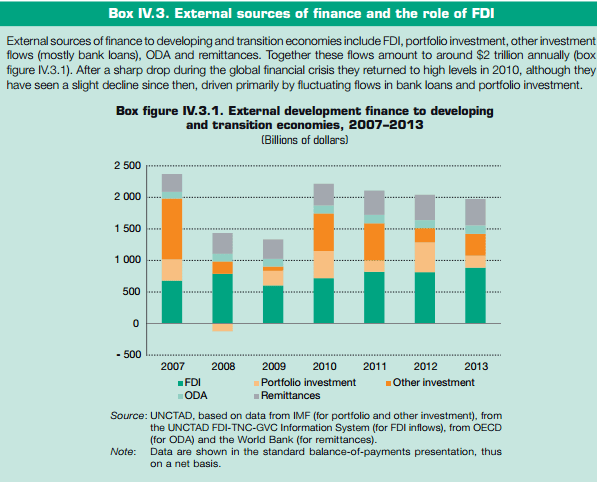

The SDG process, as clearly spelled out in SDG#17 calling on global partnerships, requires inputs from all categories of development agents, from donor governments to private business with a “corporate social responsibility”. Overall financial flows going to developing and transition economies amount to some $2 trillion a year (see box below).

PHOTO: Financial Flows to Developing and Transition Economies, including Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Official Development Assistance from donor countries (ODA) – they amount to around $2 trillion/year (source: UNCTAD World Investment Report, Investing in the SDGs, Chapter 4 )

Such flows, however large they may appear, are in fact not enough to fill the “SDG funding gap”. On the basis of UNCTAD estimates (see its 2014 World Investment Report), up to US$ 4.5 trillion would be required annually to support the SDGs in developing countries, and thus the shortfall is around some US$ 2.5 trillion.

By comparison, philanthropic investments may appear relatively modest though they are growing and forecasted by the Foundation Center to be $364 billion between 2016 and 2030. Yet philanthropy, along with the private sector, are seen by UNDP as important contributors to help fill the SDG funding gap. What makes them important are three characteristics that go well beyond dollars and cents:

- They often include unique technical expertise;

- They show a high tolerance for risk and a strong ability and desire to innovate;

- They often take a long-term view on investments.

These characteristics could be “immensely helpful when looking for development solutions that are measurable and scalable.” In fact, it is important to remember the timeframe contemplated by Agenda 2030: 15 years. This is longer than most governments and businesses are willing to contemplate. Hence the importance of drawing in philanthropists, they alone can play a major role in both jump-starting the SDG process and helping to monitor it overtime.

Related article: “SDGS: THE TYRANNY OF AN ACRONYM“

Why this Book

This is in fact a “primer” for impact investors, full of “tips” to help them understand what is distinctive about the SDG processes and learn about Kenya, its development challenges, its policy and institutions as well as the “stakeholder landscape” (i.e. who the other players are) so they can align their efforts with local needs. For anyone thinking of investing in Kenya, this is a first port-of-call, a quick way to find where to get support and make connections, how to influence and participate in decision-making, and how to set up or work with local partners.

It provides a comprehensive explanation of the role of the UN in the SDG process at country level, in particular as it operates through two mechanisms:

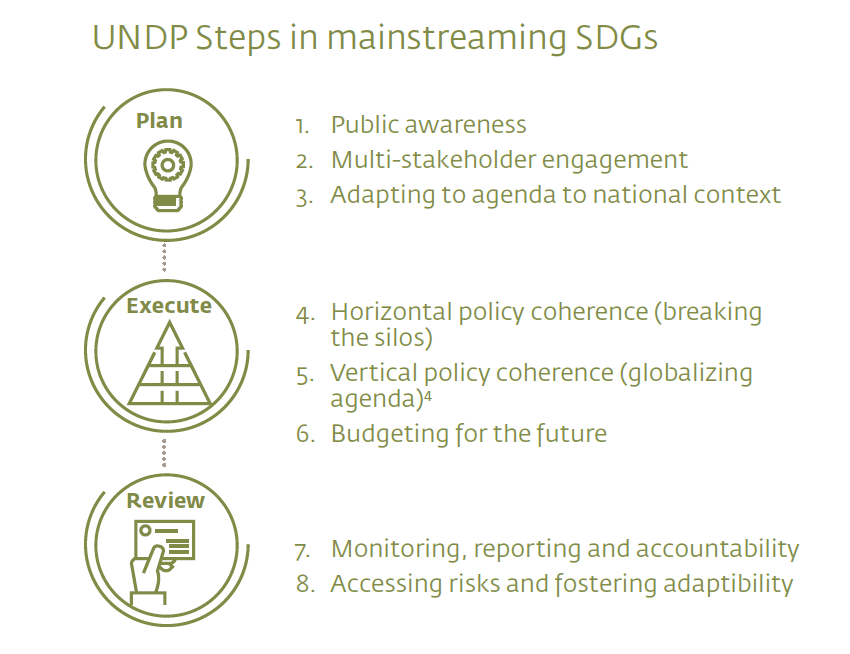

- The UNDG (United Nations Development Group); constituted in 1997, the UNDG unites the UN funds, programmes, specialized agencies, departments and offices that play a role in development in over 160 countries – Kenya included. This is how UNDG’s role in “mainstreaming” the SDGs is depicted:

- The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) which ensures collaboration between various ministries and UN agencies in four strategic areas; in this context, the SDG Philanthropy Platform is developing “pathways for philanthropists and others to engage here”. It is expected that the upcoming Medium Term Planning cycle will include such a “process of engagement” for philanthropists and businesses. However, as noted in the book, “in practice the level of engagement is still low but expected to increase in the future planning rounds.”

Perhaps this kind of honest observation pointing to weaknesses and limitations – in addition to exhaustive explanations as to how the UN and local systems work and interact with each other – makes this investment “primer” truly useful.

Take another example. The reader is warned that not all partners may be as trustworthy as they seem: “Young foundations may also have weak or unclear division of governance and management mandates, meaning that emerging partnerships risk being personality-driven rather than based on structured agreements and organizational level buy-in.”

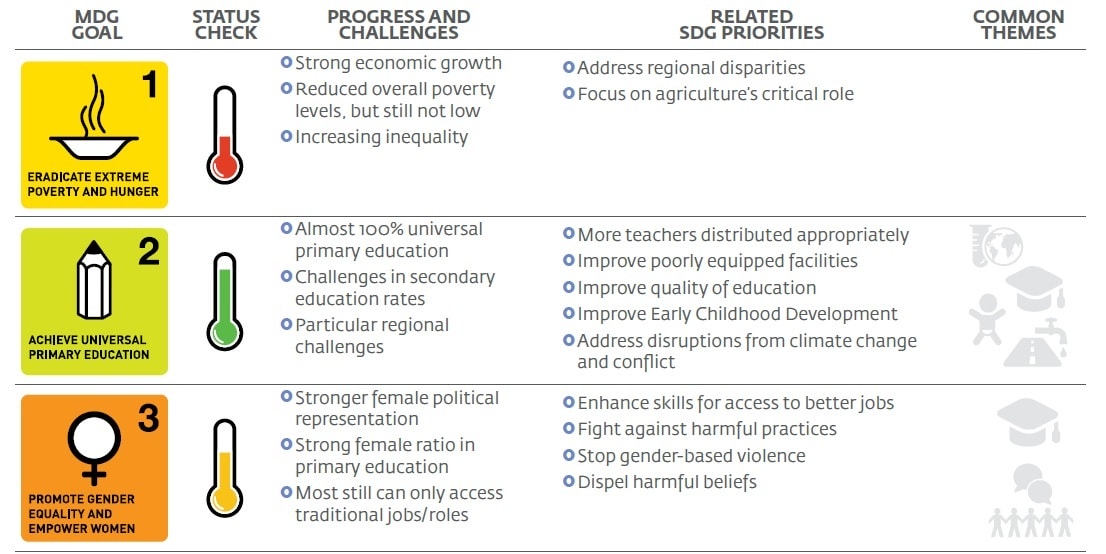

Or in giving Kenya’s scorecard on the Millennium Development Goals, it notes that it is one “with mixed results. Since 2000, successes have included improved net enrolment rates in education, and greater promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women. However, much remains to be done in terms of eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, reducing child mortality, combating HIV and AIDS, malaria and other diseases, and especially improving maternal health.”

Or again: “Civil Society in Kenya has come under much criticism of late. There is a growing perception that the sector lacks transparency and accountability, suffers from poor compliance standards, does weak accounting of sources of donations and insufficiently monitors and measures the social impact of donations received.” And later in the book (Chapter 3), it is noted that the processing of cross border donations by the regulatory authorities is “unclear and arbitrary”.

Finally, regarding political risks, the book is strikingly honest, highlighting the fact that decentralization or “devolution of power” which is one of the government’s new “flagship initiatives”, could in fact prove contentious. With the next election cycle, now scheduled in 2017, there will be widespread political campaigning that “will likely have the effect of distracting from economic and social investments aligned to the SDGs and move to short term potential electoral gratification activities and events.” And the book doesn’t shy away from recalling that “There has been serious political polarization and violence in the past, notably after elections in 2007.”

This kind of talk is very refreshing and considerably increase the degree of confidence one may have in the advice provided.

Photo: United Nations Office in Nairobi, Kenya, established in 1996. It welcomes visitors with the sign “karibuni” which plays on the Swahili word “karibu” for welcome.

Why Go to Kenya

Other countries in Africa are in worse conditions, and on the face of it, might require more attention than Kenya. Yet, Kenya makes sense. This is how the primer defends the choice:

Nairobi is an economic and financial hub for East Africa. A well-educated and hardworking professional workforce and the ease of logistics and communications are huge positives. The country’s globally competitive information technology services, innovations in money transfer and its growing intellectual pool of competitive, energetic and enterprising local human resources, place Kenya ahead of its peers in the region.

In short, it is relatively easy to work here and for any philanthropist venturing out, this is probably one of the best places to start – helped along by the language (English) and the famed Kenyan entrepreneurial spirit. And, as the Kenya’s “MDG scorecard” shows (mapping the extent of progress made since 2000, including shortfalls), there is still much to do in many areas, from agriculture to health to gender.

The book is divided in five chapters, and the first four are useful to anyone interested in Kenya, regardless of the area of concentration. Practical advice is provided, like, for example, a comprehensive list of applicable laws that govern the functioning of philanthropists and their activities in Kenya is provided. Investors are advised to keep in mind, going “beyond the global SDGs” that there are “three levels of governance and accountability that influence Kenya’s development priorities and structures: Pan-African and regional, national and subnational [county level]”, and most of Chapter 4 is given over to explaining this complex structure. And it can be fairly complex; for example:

Education is a function that is not devolved, with the responsibility for implementation remaining at the national level. But within education, Early Childhood Development (ECD) is a devolved function; thus the implementation of ECD-related targets lies with the county governments.

The first chapter gives an overview of the SDGs; the second provides a balanced overview of a 45 million people country with huge potential and great needs and gives a goal-by goal progress report on the MDGs and how these link to the SDGs; the third depicts the current state of philanthropy in Kenya and its institutional framework; the fourth is an introduction to the main national and subnational development policies and the mechanisms set up so far to help support coordination and intermediation, as well as key funders; the fifth is focused on the needs and activities in the education sector that is seen as decisive in the Kenyan context to achieve the SDGs.

Why Give Priority to Education in Kenya

The Government of Kenya invests heavily in education, a remarkable 6.4 percent of GDP. And education is one of the areas that has received the most philanthropic investment in the country. Several major stakeholders have given it priority: first, the SDG Philanthropy Platform, currently focused on education in Kenya at all levels; and second, the Kenya Philanthropy Forum, the first locally-based alliance of foundations (co-created with the Platform and local partners) with more than 70 participating foundations and trusts, with special sub-groups focused on the education sector.

Moreover, we are told that “it is an exciting time to be involved in education as a philanthropist. due to a shift in government thinking which aims to be more inclusive to non-traditional partners, such as philanthropy and the private sector.”

Education made great progress in Kenya in the past 15 years and essentially achieved the MDG goal, but there is still much to do, as the “Scorecard” of Kenya’s “progress under the MDGs” shows, together with what remains to be done under the SDGs (Education was the second MDG goal and it focused only on primary education):

In spite of all the efforts, more than a million children are still not in primary school – thus, the “almost” 100% universal primary education indicated in the above table is a little misleading.

Other problem areas include secondary education, regional disparities (particularly in arid and semi-arid areas), uneven quality in education and learning, threats from climate change and conflict, poorly equipped facilities etc.

Photo: Turkana County Governor Hon. Josephat Nanok (R) with Lundin Foundation and Oil Corp representatives inspecting one of two facilities they constructed and equipped, during the inauguration at the Lodwar Vocational Training Centre, (oil has recently been found in Turkana) Source: UN

How can philanthropists engage in education? Utilizing existing platforms, such as the Kenya Philanthropy Forum and the SDG Philanthropy Platform, they can help to improve education, “in line with the SDG call for partnerships that create opportunities for collaboration between government, philanthropy and the private sector.”

But education is probably just one area of concentration. Elsewhere in the book, the reader is reminded that the SDG Philanthropy Platform “envisions to expand and explore other SDGs of interest to philanthropic sector and of priority to the government.”

Indeed, the areas of SDG interest are multiple and with climate change, one may expect new challenges to arise over the next fifteen years. But perhaps Kenya has taken, with the help of UNDP and this “primer”, a step towards greater reliance and ultimately sustainability. At least, the government is better prepared to deal with new challenges and open the country to social investors: What this book does particularly well, is explain in detail the institutional mechanisms in place in Kenya to support Agenda 2030 and how an philanthropist can take advantage of the partnerships on offer – regardless of his or her particular areas of interest and/or new, unexpected challenges.

Recommended reading: “YOUTH KEY TO THE SUCCESS OF THE SDGS IN KENYA”