Now more than ever, women are at the forefront of social change and innovation. And there’s an urgent need to bring a gender perspective in all domains, including science diplomacy. The importance of gender equality and women empowerment has been defined as a main global objective to address. This importance has turned gender equality and empowerment of all women and girls into one of the sustainable development goals in the 2030 agenda of the United Nations. In the United States, more women are running for Congress and public office than ever before, women outnumber men in the current Spanish government, and gender equality was for the first time a top priority for the G7 during Canada’s presidency. In Latin America for example, the advancements of the empowerment of women have led to significant changes such as reducing poverty and inequality.

On the other hand, the underrepresentation of women is apparent in the fields of academia and diplomacy. In the USA, while women make up more than half (51.5%) of assistant professors and are at near parity (44.9%) among associate professors, they accounted for less than a third (32.4%) of tenured professors in 2015. Furthermore, women held over half (57.0%) of all instructor positions, which are among the lowest ranking positions in academia.

The figures for women in diplomacy are even less encouraging. 85% percent of the world’s ambassadors are male, and only four of 73 Presidents of the United Nations General Assembly were women since 1945 to date.

However, some promising milestones are worth pointing out. The UNFCCC Secretariat has been monitoring gender balance since 2013 in technical and decision-making bodies established under the Convention. For the first time, this year (COP24) more than half of these bodies had 38% or more female representation. Furthermore, there was a record number of female delegates elected to the position of Chair or Co-Chair of these bodies — nine out of 28 possible positions. Though these improvements represent steps in the right direction to achieve the goal of gender balance, much remains to be done.

As female science diplomats, we seek to not only expose or bring awareness to these trends but also to map potential ways to overcome the remaining obstacles in our chosen field. This article is co-written to explain and bring to light the qualities and attributes that we feel women, including many among ourselves, are uniquely able to bring to science diplomacy — a rather new niche evolving at the intersections between international relations and several other more technical domains.

SDL2018 Alumnas

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science Diplomacy & Leadership Workshop held at the end of June 2018 (#SDL2018) at the AAAS headquarters (Washington, DC, USA) gathered twenty-eight science and diplomatic professionals from fifteen countries for a week-long crash course on science diplomacy. In addition to being a valuable learning and networking opportunity, the workshop offered an occasion for sixteen women to share their perspectives on the role of women in science diplomacy. Willing to continue the exchange of ideas, and with the joint recognition of the need to take a closer look at the gender representation in science diplomacy, this group of alumnas started the — as for now — informal network “Women Science Diplomats” (#SciDiplomettes) and wrote this joint article.

We are well aware that the scope and definition of science diplomacy is far from being clear cut. Thus, let this joint contribution also be one of the tiny steps taken towards the encouragement of further reflections on what the possible paths to science diplomacy should be, especially in view of defining the relations, intersections and boundaries between science diplomacy and gender studies.

SDL2018 gathered many inspiring speakers, which stimulated further conversations between us, both during and outside of the formal program. Discussions on our scholarly explorations and career paths have led to selecting several examples, which we would like to bring to wider attention.

Value Added by Better Representation of Women

One of the main reasons we find it of great importance to stress the need for more gender parity in science diplomacy, as well as in science and diplomacy, is the value of diversity.

Certain studies support the claim that decisions made and executed by diverse teams deliver better results and diversity of decision-makers has an impact on constructive politics. Collaborative teams and research panels, which are based not only on experts with diverse theoretical convictions but also founded on the aspiration to include a certain gender parity component, might end up also benefiting from an academic and scholarly interaction among thinkers with a range of views. These are inherently, implicitly or explicitly based on different personal values, experiences, walks of life and worldviews. Debates among such a panoply of peers and their commonly acquired research findings and recommendations should be valued in terms of having been a subject of more critical evaluation and being less affected by the prevalent biases.

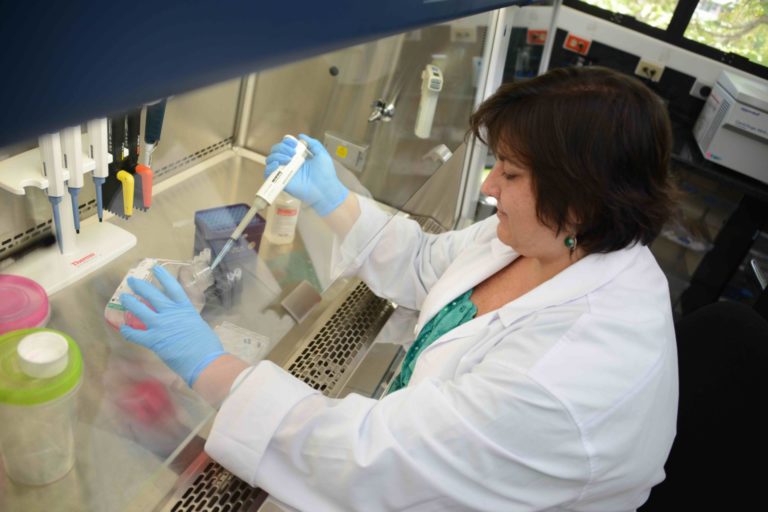

UNESCO has acknowledged that underrepresentation of women in STEM results in a loss of talent, viewpoints, and ideas, which ultimately reduces the development of each country. Science diplomacy, as a relatively new domain, should strive to depart from such earlier pitfalls and offer more promising grounds for talented female science diplomats. Likewise, better integration of women in STEM science domains should be viewed in the light of an earlier recognition that in certain parts of the world, STEM fields are considered to be vital for economic and social development, as well as alleviation of poverty.

These assumptions and encouragement for more pronounced gender parity in various international collaborative formats are written while also bearing in mind the somewhat challenging task it will be to accomplish with the full knowledge of the talent and potential that is being left outside of the top-level training in STEM. A UNESCO report outlining the participation of girls and women in STEM noted that the observed gender gap begins in early childhood, and becomes more prevalent in the higher education sector.

Additionally, the lack of visibility of women among the highest fields in academia, including its portrayal in US entertainment media, reinforces the imposter syndrome that many women feel in professional spaces. A 2014 UNESCO study showed that while 44% of STEM graduates are women they make up just 29% of the research workforce. These differences translate to smaller numbers of women choosing a career in science diplomacy in a manner that is contributing to national, multilateral and international scientific research, expert committees and such public occasions as high-level conferences, eminent discussion panels, etc.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“The Ripple Effect of Investing in Women and Tech”

“The Ripple Effect of Investing in Women and Tech”

“Small Loans for Safe Water: Unleashing Women’s Power”

“Small Loans for Safe Water: Unleashing Women’s Power”

The call for more pronounced gender parity and more visibility of gender parity in STEM is a cause promoted with a full appreciation of how important it is to offer role models for aspiring researchers. Such efforts should be combined with a promotion of policies and practices tailored to address discrimination.

We are aware of the existing barriers standing in the way of a more gender-balanced representation among the diplomatic ranks. These challenges include the appointment of women in senior diplomatic and international negotiation positions, which translates into the degree of influence of women in negotiation and decision-making processes.

An example of this is found in the study “Gender, International Status, and Ambassador Appointments,” which has concluded that women are less likely to be assigned to higher status positions. In 2014, even those 15% of women who had reached the goal of attaining diplomatic rank still faced a clear challenge in terms of having fewer chances to be appointed to the most prominent ambassadorship positions. Furthermore, we acknowledge that this is just the tip of the iceberg since these statistics do not show the gender parity dynamics faced by international organisations and their institutions, international non-governmental organisations, as well as other sectors with which we are less familiar.

Departing From Path-Dependency

The reason we find it important to highlight several statistics on the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions across different sectors and structures is due to the current trend of underrepresentation of women in leadership positions in a variety of domains, thus presenting a great risk of replication of this reality in such a nascent field as science diplomacy.

Although the evidence is showing a changing pattern, several factors including unconscious bias, lack of role models, and certain restrictive constellations of family responsibilities continue to limit women’s participation in leadership and diplomacy. These problems are, at the core, similar to the challenges that women face in other ambits.

Specific to diplomacy, though, is the consideration of appointments requiring one to work abroad, for example, family related considerations. Spouses transition from a breadwinner to a “non-working partner” — for example, men struggle to accept themselves as a dependent. Furthermore, children might not always be able to continue their education in other languages and circumstances. These and other caveats may make it difficult or even impossible for women to properly address the needs of their families and continue to simultaneously climb up the professional ladder.

We fully appreciate the importance of leadership training, mentoring and sponsoring initiatives to address the underrepresentation of women. Some of the good practices which we would like to promote among wider audiences are the following.

Homeward Bound is a global initiative that seeks to create, over a 10 years span, a network of 1,000 women with a scientific background to influence or become decision-makers for a more sustainable future by giving them a 1-year leadership training that culminates in an all-women expedition to Antarctica. In some countries, such as Latvia (see Forbes, Eurostat), there are plenty of women in senior positions who can serve as role models for young professionals.

Beyond the examples discussed in the earlier paragraphs, we also note on a more general level that the overall discourse of female leadership is deeply rooted in societal values, beliefs, and culture, especially the varying perceptions and expectations attributed to women. Thus, issues faced by women in the science diplomacy field are, by and large, intrinsic to those faced by society.

The diversity among the SciDiplomettes has led to thought-provoking discussions and a more profound awareness of our shared and varied experiences. One of our uniting messages is a joint recognition of the importance of mutual support to promote talented and capable female peers.

In this article, we highlight certain issues which we deem to be crucial for the future of science diplomacy and bring attention to the cumulative effect of barriers affecting women in “science diplomacy,” having to overcome the ones faced by women in STEM and by women in diplomacy. It is a call for further reflection and action both among ourselves and to a wider circle of thinkers and actors interested in the overall discourse evolving around a burgeoning “science diplomacy” concept. Being supporters of an incremental process, we see this joint publication as a starting point for more thorough consultations on the potential future cooperation in order to uphold and advance the values and perspectives captured in this overview.

Disclaimer: All authors of the article are writing in their personal capacities.