Religious pluralism matters if democracy is to survive. Multiple examples and counter-examples prove the point, the latest in Afghanistan. On 15 August 2021, sooner than expected, Kabul fell to the Taliban, an Islamist fundamentalist group in Afghanistan. While taking control of the deserted presidential palace, the Taliban announced that the country that had attempted to become a democracy would reappear as the Islamic Emirate.

Historically, in Afghanistan, the expectation has been that state rulers would be Muslim and deliver justice and security according to Islamic dictates. As a result, when the Afghans viewed the previous administration to be failing in providing people with justice and security, the ground became ripe for the Taliban to take back control by promising good governance through Shari’a law, the religious regulations of Islam, broadly understood. The change took place despite the fact that the Taliban have never stopped exploiting the critical issue of justice with a plain record of abusing power two decades ago.

If we look back at their history of governance, the Taliban ruled a civil-war-torn country during the 1990s through the strictest interpretation of Shari’a law. Thus, their version of Islam was propagated by forbidding any liberal analysis of the religious codes. They demonstrated a form of religious intolerance, which not only directly attacked the country’s pre-Islamic Buddhist heritage by destroying mammoth Buddha statues at Bamiyan but also set an atrocious example of curtailing the freedom and rights of their fellow believers.

For example, the Taliban employed a religious police for ensuring that the men grew beards; women wore burqas, a whole-body covering garment; and if they were unaccompanied by male guardians, they could be beaten.

Simultaneously, non-Muslim minorities were made to shrink to a tiny fraction of society; schools for girls were closed down; soccer and music were forbidden; legal guarantees for women were outmaneuvered by adverse norms.

Consequently, women were severely disadvantaged in justice, employment, health, and hereditary matters. Understandably, the Taliban rule came to be synonymous with not a successfully functioning government, but a grueling nightmare.

In other news, the June 30 Revolution (2013) in Egypt, which started as a protest against worsening economic plight, shrinking public service, and a chain of events pushing for sectarian violence, ended up ousting Mohamed Morsi from power. Morsi’s religiopolitical party, Muslim Brotherhood had its political wing officially dissolved in August 2014, and the ensuing attacks by the Islamists were brought down by counterinsurgency measures.

Nevertheless, these upheavals have sharpened the awareness in the Arab World regarding the impediments for peaceful coexistence caused by sectarian hatred and chaos. Consequently, Inas Abdel Dayem who heads Egypt’s Ministry of Culture with its post-revolutionary administration has been decisive about deepening the pluralistic values of the society in order to preserve its ancient heritage of openness towards disparate cultures.

The United States has also experienced heightened risks of political unrest in recent times. Mass shootings hitting a record high in December 2019, hate crimes detected to be on the rise in November 2019, and police brutality and discrimination becoming understood to be affecting the Black population unjustly in 2020 led to the widespread realization that the crises can be overcome only by stopping the increasing polarization of people. At risk is the vast egalitarian promise of America that people subscribe to, especially immigrants, despite their religious, cultural, and racial differences.

If the homicide of George Floyd on the 25th of May, 2020 led to strings of protests to challenge racism in every sphere of society, it also highlighted the urgency of re-imagining the social approaches for keeping the communities safe. Against this backdrop, President Joe Biden’s declaration in his inauguration speech, ‘disagreement must not lead to disunion,’ is very apt and timely, for a prodigious and diverse nation like America cannot realistically harp on assimilation for unity.

Instead, uniformity has to be achieved through the tolerance of differences regarding values and beliefs. In what follows, I will argue that the goal of achieving pristine purity through forming a collective identity is a myth, which is why it is not rational to impose the predominant religion on the minorities and the marginalized groups of a nation.

In fact, the demand for compliance with the dominant views can easily backfire. Therefore, I will also enquire whether we can create effective democratic responses not only against the futility of asserting cultural purity and identity but also for promoting tolerance and understanding regarding our increasingly diverse world.

Religious Pluralism: The Right Response to Cultural Purity and Identity

Given the constant disintegration of socio-cultural bonds through the global flow of capital, religious pluralism implies an effort to realize that each religion forges its unique path towards Divinity, which opens up the possibility of understanding that all religions are rooted in historical reality. However, neo-liberal values are not effective enough to fend off the fear of the unknown cultures and religions, which have now become part of Western society due to globalization-induced movements of people within its boundary.

Tensions are particularly high in the supposed conflict between Western and Islamic worlds, given the tragedy of 9/11 attacks. Islam in France also challenges its prized model of laïcité (separation of state and religion) due to the Muslim community’s lack of a corporate structure – this is in contrast with the dominant faith communities like the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish groups that have such structures and therefore relate well to the secular state’s dynamics. This in turn exacerbates laïcité’s deep-rooted discomfort with religious estrangement, which is considered to be a threat to the freedom the system wants to guarantee.

In order to lift religio-cultural groups from the constricting idea of the “clash of civilizations”, more than tolerance is needed. This is so because tolerance can only enable opposing religious groups to coexist without creating a real engagement with each other’s viewpoints.

On the one hand, it is convenient to demand that members of unalignable religious groups should attempt to maintain the coherence of Western societies and that, in turn, could lead to the end of practicing the non-dominant faiths in a meaningful manner.

On the other hand, a few religious groups assert the urgency of granting their communities the privilege to continue with their own unassimilable ways. In order to avoid the dilemmas during policy-making, careful attention has to be given to the concepts and practices that the communities want to put forward, rather than the religious loyalties they embody.

It is generally observed that non-democratic states find it difficult to ensure the rights of religious minorities. These states tend to give preferential treatment to some religious communities over other ones (e.g. Iraq), and/or marginalize some groups (e.g. China with the Uyghurs).

Since globalization has widened the scope of information sharing and promoted public knowledge about universal human rights, the development of citizens’ skills in cultivating civic and political qualities that enhance democracy should be the modern democratic state’s decisive goal.

For this reason, a democratic government’s policies regarding religion should be placed under close observation: In particular, one should monitor how much the governments can protect majority faith, when such harboring becomes unfair cooperation with the faith community, and what changes the state’s support towards majority faith into outright discrimination against its religious minorities.

Multi-faith societies: The example of India

India, with the second-largest population in the world, fourteen official languages and more than three hundred dialects, still baffles the world with its achievement of relative peace, despite starting out with an impoverished economy. I think the foresight of the founding fathers, which was unambiguously pluralistic by endowing every home-grown ethnic and religious group with a fair chance of thriving within its boundary, has to be given the real credit here.

This also means that the legal authorities can decidedly intervene in the undemocratic traditions of a particular religious group. For example, the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) Act exist in India, because it is deemed that the conventional legal framework does not ensure adequate safeguard for Hindu lower castes.

However, the democratic process itself requires that ordinary people belonging to all religions, castes, and tribes have faith in the vital institutions of the government like the Judiciary and the Election Commission.

For this purpose, the currently dominant view of the vast territory as fatherland as well as holy land is not ultimately beneficial; because this, in turn, creates a latent division between the communities belonging to Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, who demonstrate both the allegiances, and the communities belonging to Christianity, Judaism, Parsism, and Islam, who consider their respective holy lands in the Middle East.

Hence, the European model of nation-state focusing on the unity of religion, culture, and geography requires broader scrutiny in order for the Indian model of tolerance, democratic bulwark, and judicial activism to retain its pride of place on the world stage.

Multi-faith societies: The example of Britain

Similarly, Britain has earned its exemplary position in the world as a multi-faith society. Starting with the Norman Conquest nine hundred years ago through to the Irish immigration more than a hundred years back, as well as the arrival of the Indian and Caribbean diasporas from the early 1950s in order to aid the British industrial growth, Britain has been a successful home to varied religious communities by cultivating a culture of tolerance that started to be properly articulated in the late seventeenth century.

Part of the success of accommodating the recent diasporic Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus lies in Britain’s recognition of the forcefulness of character and capacity, intelligence and innovation displayed by the multi-religious peoples in strengthening the foundation of a welfare state that the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple, has been championing since the mid-twentieth century.

The question for today’s Britain is how to protect the base of the carefully built welfare state by highlighting the values and pledges that bind the multi-religious citizens together in a predominantly Christian country.

As a democratic society, the political will to view Britain as a pluralist ambiance is there. The understanding that a general respect should prevail for those who worship differently is there as well since the varied lifestyles promise newer socio-economic opportunities for more and more people.

However, the social system has not fully caught up with the common political perception of negotiating other beliefs and non-belief within expected cultural boundaries. This is why the Commission on Religion and Belief in Public Life (2015) is a welcome initiative that recognizes the exigency of religious education in preparing youngsters for life in twenty-first century Britain.

Through the recommendations that religious education should have a secure place within the humanities, and be included within the English Baccalaureate, the Commission shows how sound religious education is crucial for building a tolerant society.

Learning democracy and religious pluralism by practice

In the end, the institutional nature of participation in public discourse – learning democracy by practice – cannot be emphasized enough. It has been a neglected aspect of today’s philosophy, which has to be rectified if we are to achieve tolerance and religious pluralism.

How one finds one’s own space of belief and accepts others with theirs, which might contradict one’s own position from time to time, has to be demarcated in the light of historical reality. Indeed, religio-political conflicts and state management of the issues—and not a rudimentary picture of clashing civilizations—will determine the future shape of religious pluralism in global politics.

From this perspective, the United States and the United Kingdom have to play a leading role to help reduce tensions among pluralism, tolerance, and democracy. This is particularly important in a world of shifting geopolitical powers, as other emergent powers including China and India will have crucial roles to play in the near future regarding religious pluralism on the international stage.

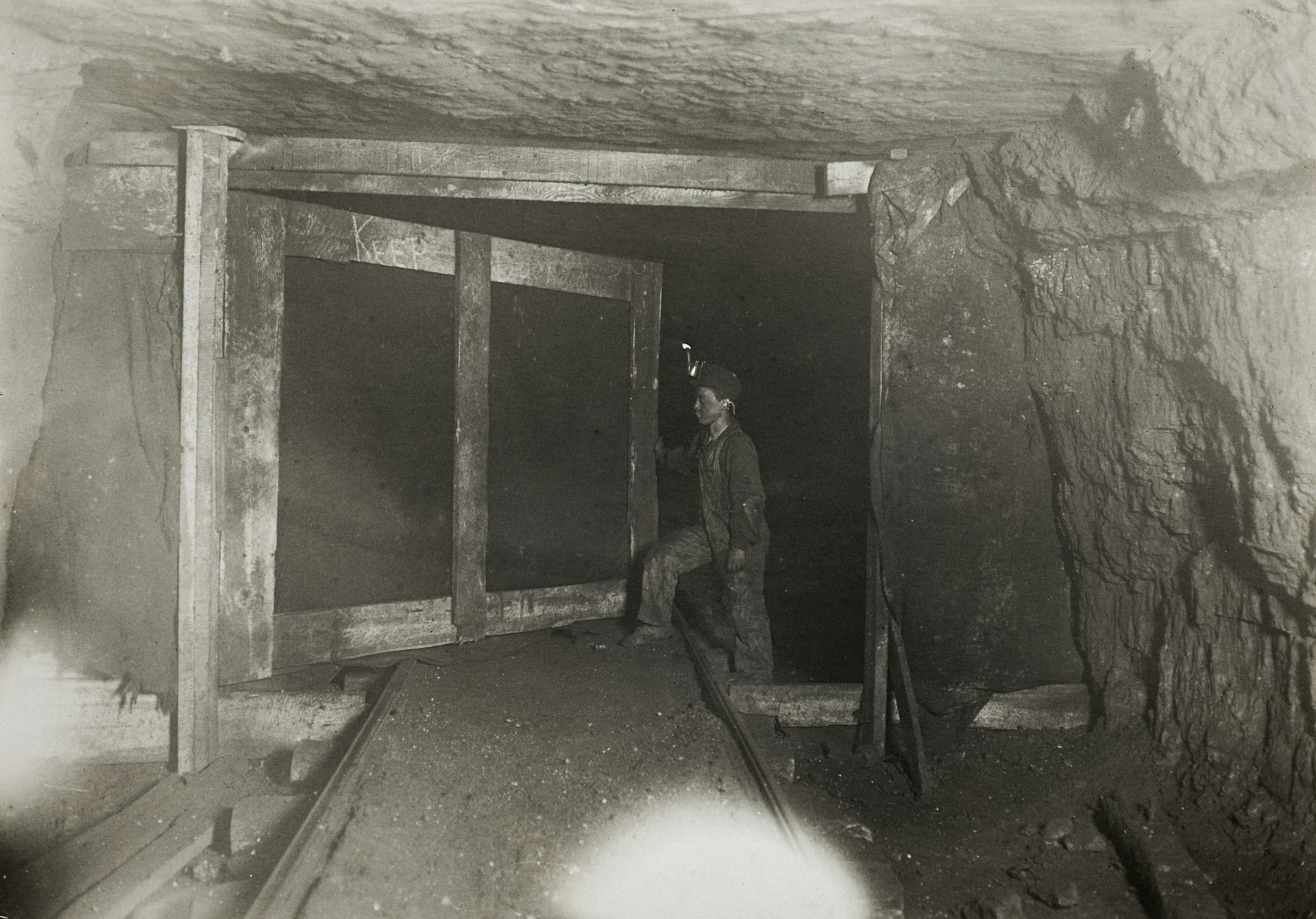

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Afghanistan under Taliban rule, return of the burqa for women Source: Image by David Mark from Pixabay