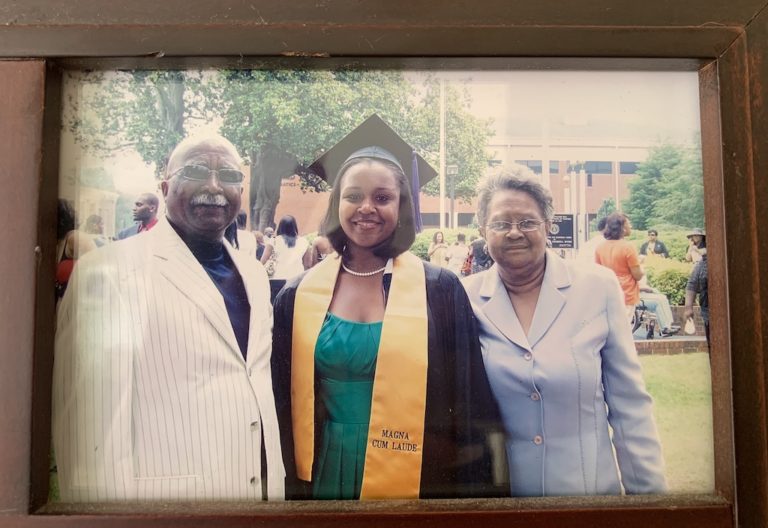

I was raised to be strong! I am the eldest of my parents’ two daughters but my father is the third of seven sons. I am logical, shrewd, and focused on problem-solving, partly because my father taught us to look at situations void of emotion. He did not want his daughters to be taken advantage of and definitely did not want us reliant on a man for our financial stability.

My father wanted us to understand and embody strength because of global racism and the mythology of White Supremacy.

He often said that we needed to be twice as good to have half as much and he promoted formal education — especially at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU’s) in the U.S. because my history and my truth would not be taught at Predominantly White Institutions (PWI’s).

He promoted formal education because it would give me the language and power to understand racism and its effect on every aspect of my life. My father’s lack of formal education is why he promoted it in us so much.

I recognized this power when I attended graduate school at Howard University in Washington D.C.

While visiting, I fell in love with the heterogeneous body of Black folks. It was then I realized that we were not a monolith yet the experience of racism held us together. It was like we had a secret power when we were all together; I needed that power; I drew from that power at each Black institution I attended.

As a Black woman, I find myself exclusively attracted to Black men. I am drawn to their stride, their confidence, their power, and their pain. The myth of White Supremacy gives us something in common and our love and commitment to one another is a radical action that collectively denies our oppression and our oppressors. Loving a Black man is like magic — however, the same force that provides commonality also has the potential to drive us apart.

My first relationship at Stillman College deteriorated due to outside pressures in my ex’s personal life that impacted his ability to function as my boyfriend. In addition to being a full-time student, he had two children and the inability to provide for them put a strain on his relationship with their mothers. His obligation to pay child support in addition to his tuition, left me footing the bill on each of our dates. I pushed him to create a better life for himself and his children; however, his past mistakes manifested themselves in a way that made it difficult for us to be together.

We ended our relationship, but I never considered how racism came into play until I read The Racial Contract by Charles Mills during my time at Howard University.

Related Articles: The Fight for Reparations | Impact of a Murderer

Mills is a Jamaican philosopher who used the tenets of the social contract, a political theory supported by White western philosophers Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant, to show that no such contract exists for Black folks. Instead, he illustrates how those tenets are used to create a “racial contract”, which permits White people to oppress and exploit non-whites and violate their own moral ideals in formal and informal ways.

The myth of White Supremacy cannot be neatly categorized because it violates the moral code in which democratic societies were founded on and function from today.

Such a revelation forced me to evaluate how racism affects my personal life. What I discovered was jarring; racism is the third person in my romantic relationships.

I am the quintessential over-achiever, this characteristic is embedded in my DNA, but the majority of it results from my upbringing and early understanding of racism. I took my father’s notion to heart and was aggressive about attaining an excellent education because I knew it was an essential form of currency in a White-dominated world.

Yet, my achievements were always front and center in my romantic relationships.

The denial of a Black man’s humanity and the inability to provide for himself or his family has a historical legacy rooted in racism. I say this not to absolve Black men from their personal choices, but to recognize that there is an established system that encourages Black trauma and in return calls them failures when they cannot overcome such trauma.

It’s an acknowledgment of a system that denies Black women a full range of emotions.

This dynamic is at the heart of many Black relationships. How much do I forgive him due to the effects of racism, and how much do I tolerate from her due to the effects of racism? This is a delicate balance that is difficult to navigate in any romantic relationship but is far more difficult when the effects of racism are present. This dynamic has left me single and at times, emotionally bankrupt.

The global pandemic has exposed this existence for many Black women I am connected to through the diaspora. Black women have to deal with the real possibility that their boyfriends, husbands, sons, grandsons, and nephews might not come back home alive. If they do come back alive, they may arrive without their dignity due to the loss of a job, or a traumatic experience and lack the emotional intelligence to communicate their pain.

Black women have to wonder should they celebrate their accomplishments at the behest of the Black men that they love? Should they become single mothers and struggle with the stereotypes attached to that type of motherhood? Should they enter marriages with Black men who they know are broken and emotionally unavailable? It keeps them perpetually asking questions like what does it mean to be a strong Black woman and what are the costs of that strength?

My strength has cost me many romantic relationships, yet it helps me fight global racism, and proclaim from each of my platforms that White Supremacy is a myth. The loss of romanticism is a worthy sacrifice for the liberation of my people. Without such a sacrifice the romantic relationships of Black folks will continue to suffer. My dream is different from Dr. King’s: my dream is that Black love is not a radical action, instead it’s just love.

—

About the Author: Dr. Sherice Janaye Nelson is a speaker, author, professor, mother and consultant. She is a Black Diaspora expert who focuses on the political, social, and economic effects of chattel slavery. This expertise has helped her serve her clients as a diversity consultant and founder of Dr. Janaye Executes. She is also the Executive Director of the Black Leadership Roundtable and a member of the advisory board for the Center for Racial Justice at Dillard University. Dr. Nelson’s new book The Congressional Black Caucus: Fifty Years of Fighting for Equality is due out Spring, 2021. She is currently a professor at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Dr. Nelson with her younger sister and parents in Oakland, Calif., circa 1992. — Featured Photo Credit: Dr. Sherice Janaye Nelson.