Book Review: Platform Capitalism by Nick Srnicek, Published by Polity (December 2016) 120 pages

Platform capitalism is the latest buzzword, replacing what used to be called “eco-systems”. It is also sometimes confused with the “gig economy” or the “sharing economy”, enthusiastically embraced by politicians as the answer to the Great Recession.

Uber, AirBnB, TaskRabbit and the like are viewed as saviors, providing jobs to those who wouldn’t have any or rounding off the pay of those who make too little. Their apps create a digital space where service providers and users meet; the needs of the latter are satisfied by the former while the app owners take a fair percentage off every transaction.

The Blessed Age of Post-Capitalism?

Technology enthusiasts see platform capitalism, created by the digital revolution, as a benign form of capitalism ushering in a new blessed age where people come into their own, workers find instant demand for their services and consumers get what they want at the tap of a button on their smartphone.

Before we go on, let’s get one piece of semantics out of the way: Platform capitalism should not be confused with the “sharing economy” (insofar as it exists at all). Platform capitalism has nothing to do with “sharing” in the sense of an exchange of goods or services at no cost to those engaged in the exchange. Platform capitalism is capitalism pure and simple: You pay for the goods and services you get, nothing is free – even if transaction costs tend to be lower online. Lower but still substantial: Uber, for example, creams off 25 percent of every taxi ride. The difference is that it’s not done through an exchange of cash in the real world, it is done digitally.

And, according to the proponents of platform capitalism, there is an added advantage: The middleman is cut out, costs to users are thus automatically reduced. This is the capitalism of the future, they enthuse. Thanks to the digital revolution, we are into the age of “post-capitalism”.

Not true, argue the critics: The basic exploitative nature of capitalism has not changed. Middlemen are replaced by new gatekeepers. “Many of the old middlemen and retailers disappear but only to be replaced by much more powerful gatekeepers,” complained one disgruntled German blogger.

Is platform capitalism heralding a bright new future or is it just the latest form of exploitative capitalism?

In the Photo: Uber, AirBnB, TaskRabbit and the like are viewed as saviors, providing jobs to those who wouldn’t have any or rounding off the pay of those who make too little. Their apps create a digital space where service providers and users meet; the needs of the latter are satisfied by the former while the app owners take a fair percentage off every transaction. Photo Credit: Pexels

So, who are those “powerful gatekeepers”?

The owners of platforms, of course. Journalists and intellectuals do not like them much. On the UK Guardian, Evgeny Morozov, author of the “Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom” and a visiting scholar at Stanford, had, predictably, some harsh words. “Most of the current big-name platforms are monopolies, riding on the network effects of operating a service that becomes more valuable as more people join it,” he wrote. “This is why they can muster so much power.”

Others in academic circles agree. Frank Pasquale, Law Professor at the University of Maryland, in an article in the Yale Law and Policy Review argued that platforms, instead of promoting fairer labor markets due to low cost of entry, increase precarity by “reducing the bargaining power of workers and the stability of employment.” Discrimination is also increased, a result, inter alia, of ranking and ratings systems. Growth is undermined and wages are reduced as workers scramble for gigs.

So, in this controversy, who should we believe? Is platform capitalism heralding a bright new future or is it just the latest form of exploitative capitalism?

One forward-looking academician, Nick Srnicek, a young lecturer in international political economy at City, University of London has recently come up with what is, at last, a clear and balanced answer in his book “Platform Capitalism” (published by Polity, December 2016).

Who is the Author?

Though Srnicek is young (he was born in 1982), he is not new to this debate.

It all began in 2013, the year he got his Ph.D. from the London School of Economics. That year, together with Alex Williams, he wrote an influential and much debated monography, called the “Accelerate Manifesto“. Viewed as the founding text for “accelerationism,” a new kind of political theory, it calls for an alternative model to meet the future challenges facing our society, in particular climate change and automation.

It all began in 2013, the year he got his Ph.D. from the London School of Economics. That year, together with Alex Williams, he wrote an influential and much debated monography, called the “Accelerate Manifesto“. Viewed as the founding text for “accelerationism,” a new kind of political theory, it calls for an alternative model to meet the future challenges facing our society, in particular climate change and automation.

The point is to push capitalism forward using technology, or, as Srnicek told a blogger in a recent interview: “a post-capitalist future will be built on top of the advances made by capitalism. It’s not a simple rejection, destruction or negation of capitalism, but rather its re-purposing. Now a key part of this, which has been controversial, is the belief that existing technology can be deployed in ways that benefit people rather than profits.” (emphasis added)

No doubt the controversy has been fed by the exalted language in the Accelerate Manifesto. The diagnosis of what is wrong with neo-liberal capitalism is extreme: It stands accused of slowing down and even preventing technological progress. The “accelerationists” want us to move beyond the “limitations imposed by capitalist society” towards a “time of collective self-mastery” and we need to prepare and plan for it. Never mind if nothing can be found in the Manifesto about what form this “self-mastery” might take.

Which is no doubt why the next book Srnicek wrote with Williams attempts to describe this future, putting, as it were, flesh on the skeleton of the Manifesto. Called “Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work“, it was published in 2015. Described on Amazon as a “bold new manifesto for life after capitalism,” it goes “against the confused understanding of our high-tech world by both the right and the left” and calls for full automation and universal basic income. It is also intended as a wake-up call to the left, demanding a return of utopian thinking and efforts to re-organize itself.

Unsurprisingly, accelerationism has caused considerable misunderstanding with some arguing that it shows that the best way to end capitalism is to “push it to the extreme” and consume “like crazy” to “hasten the apocalypse” (this is the argument made in an interview on Vice by Steven Shaviro, who teaches at Detroit’s Wayne State University). This unfortunately overlooks (inter alia) the devastating impact of industrial pollution:

Plastic Soup from Lara Leslie on Vimeo.

In short, there has been controversy as well as unrestrained enthusiasm. For example, Neal Lawson, a political commentator and chair of Compass, a UK group pressuring for reform of the Labour party, in reviewing “Inventing the Future“ wrote that it “burst its way in” with “demands that quicken the pulse” because they are “coherent, systemic and chime with the direction of travel of our cultural and technological age.”

With all this, you might have expected Srnicek to produce some truly radical thinking in his book about “platform capitalism,” the kind of stuff one can safely overlook. Not so. Over the three months since it’s been out, the book has drawn increasing attention, including a rare compliment from the New York Times’ John Herrman in an article polemically titled “Platform Companies are Becoming More Powerful – But What Exactly Do They Want?” Noting that “platforms have long been intoxicating to investors” and that they have been the subject of “rapturous popular business writing,” Herrman writes (and you can sense his approval) that this is not the case with Srnicek’s book which “tries to situate the rise of platforms in a broader history of capitalism and to project those lessons forward.”

Related article: “FREDRICK ALMOTH ON HACKING GOOGLE, SECURITY AND TECHNOLOGY”

What is in the Book?

A first and welcome surprise: there is none of the exalted language found in the Accelerate Manifesto. Soberly titled “Platform Capitalism”, it is pleasingly short (120 pages) and to the point. In a straightforward, non academic style, it provides a sedate, well thought-out analysis. It starts with an historical overview of the rise of platform capitalism, tracing its genesis to the long downturn of the 1970s, the boom and bust of the 1990s and the 2008 crisis. The latter was followed by a burst of high risk-taking venture capital and a dearth of traditional career-oriented jobs that proved essential to the rise of platform capitalism.

Having adopted a long-term perspective, Srnicek is able to convincingly show that a structural shift in the economy has indeed occurred, that a small number of monopolistic platforms – from Google to Amazon – are responsible for shaping the economy and carving up the fundamentals to their own benefit.

Being digital, this is a form of capitalism uniquely equipped to collect and manage data. He argues that these platforms are in fact the new intermediaries between users, i.e. providers of goods and services, advertisers and consumers. Such a definition helpfully avoids emotional terms like “gatekeepers” and “middlemen”.

But platforms are more than intermediaries. They are also infrastructures that allow for user interaction and development of apps or web pages on top of the platform. For Srnicek, as he recently explained (see video below), “platforms are the only business model adequate to the digital age.”

In the Video: Talk given by Nick Srnicek at Goldsmith’s College, MFA Curating Lecture Series on 6 February 2017 presenting his book, It lasts some 40 minutes and is time well-spent.Video Credit: Goldsmiths Art

To grow, platforms rely on three driving elements:

- “network effects”: the more users, the more valuable the platform – Facebook is the classic illustration;

- “cross-subsidization”: this is the opposite of a “lean business model” whereby unnecessary branches of the business are cut off; here, a branch may be free or nearly-free, while another is not, thus, a few people pay and subsidize everyone else;

- platform rules of “service development and marketplace interactions” that are set by the platform owners: Though platforms present themselves “as empty spaces for others to interact on,” they cannot be a wild jungle; rules are needed, for example, Uber’s policy of “surge pricing” that pushes drivers to go where demand is highest.

Driven by these elements, platforms grow digitally: They extract data on every user and on how the product/service is used. They need to capture and control as much of the data as possible, their business model depends on it.

Photo Credit: Pexels

Srnicek distinguishes five kinds of platforms:

- advertising platforms (e.g. Google, Facebook): they “extract information on users, undertake a labour of analysis, and then use the products of that process to sell ad space”;

- cloud platforms (e.g. AWS, Salesforce): they “own the hardware and software of digital-dependent businesses and are renting them out as needed”;

- industrial platforms (e.g. GE, Siemens): they “build the hardware and software necessary to transform traditional manufacturing into internet-connected processes that lower the costs of production and transform goods into services”;

- product platforms (e.g. Rolls Royce, Spotify): they “generate revenue by using other platforms to transform a traditional good into a service and by collecting rent or subscription fees on them”;

- lean platforms (e.g. Uber, Airbnb): they “attempt to reduce their ownership of assets to a minimum and to profit by reducing costs as much as possible.” In other words, Uber or Airbnb charge their drivers or home-owners as much as the traffic will bear. Incidentally, for Srnicek (as he explains in the video), this may be the least viable form of platform over the long run – which probably explains why Uber is moving towards an asset-owning business model as it develops driverless cars.

Also, some platforms escape categorization. For example, Amazon and Bloomberg do not exactly fit into any of the above categories: They share elements from several platforms. Amazon rents out web services and it is into e-commerce; Bloomberg ranges from a news agency to financial services.

All these platforms have one thing in common: they tend to acquire a monopoly position. Will they succeed? If they do, consumers could face rising prices, platform workers might find their health care needs and pensions are not covered. Regarding the latter, much depends on how you define platform workers: For example, are Uber drivers to be considered independent contractors (as Uber maintains) or employees? If the latter, they would have a right to a pension, vacation and health coverage.

The outcome largely depends on local culture. Where worker unions are strong, Uber could and has run into serious difficulties, for example in France where local taxi drivers rebelled and found political support.

In the Photo: French taxis against Uber, Toulouse, June 2015 Photo Credit: Gyrostat Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA 4.0 CC BY-SA 4.0

Where unionized labor is weak, platform owners might win out. The latest battle in the US is shaping up in Seattle, with a Federal judge issuing a temporary injunction on the right of taxi drivers to unionize, and for now, it looks like Uber and Lyft are winning.

As Srnicek writes in his closing chapter, the basic question is: “Will competition survive in the digital era, or are we headed for a new monopoly capitalism?” His answer: The tendency to monopolization is “built into the DNA of platforms.” And, he notes, they have already grown into significant monopolies: for example, in 2016, Facebook, Google and Alibaba alone took half of the world’s digital advertising.

More importantly, price competition is likely to be less dominant in future: In our brave new digital world, firms will be judged and ranked in terms of their capacity for data collection and analysis. Platforms, to remain competitive, will need to “intensify their extraction, analysis, and control of data.”

Expanded data extraction is the name of the game. It’s a vicious circle and it happens at the expense of privacy.

Heavy investment in artificial intelligence is a corollary, the kind of investment Google, Amazon, Salesforce, Microsoft and Facebook are all engaged in.

Photo Credit: Flickr/Ged Carroll

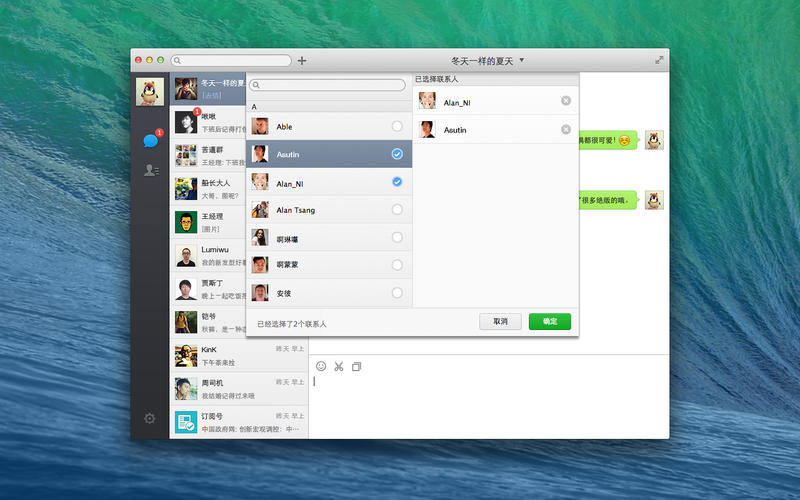

There is, he notes, another key emerging pattern: Platforms seek to dominate the interface between apps and websites, as the Chinese WeChat does where users simply access any business or service they need without ever leaving the platform. Thus WeChat derives revenues from e-commerce and not advertising (as Facebook still does).

As Srnicek sees it (and he expands on this in his video talk), the WeChat model of a monopoly platform is our most likely future: We are headed, like the Chinese who have no alternatives (perhaps an effect of the Communist government?), towards “one massive, closed, expansive, monopolistic platform(s).” A sort of silo where everything takes place.

The alternatives – platform corporativism, i.e. owned and controlled by the workers and public platforms, state-owned and regulated – are a lot less likely. Imagine, he says, going against Uber: Could a coop made of drivers and users move away and form their own competing platform? Not likely. As to public platforms, how do you shield them from the State’s own security systems, a.k.a. spies? How do you prevent them from becoming a new Big Brother Watching You?

For the moment, Srnicek has left the solutions “blowing in the wind.” Is our set of anti-monopoly rules adequate for the digital age? He doesn’t think so. In the video (not in the book), he reminds us that our current anti-trust legislation was devised in the 1930s for another kind of economy. I agree, but I also think something can be done, surely a framework of rules that would protect users without adversely affecting platforms could be devised.

Our future cannot be left in the hands of Big Brother, whether private or public.

Recommended reading: “21ST CENTURY EDUCATION FOR A 21ST CENTURY ECONOMY”