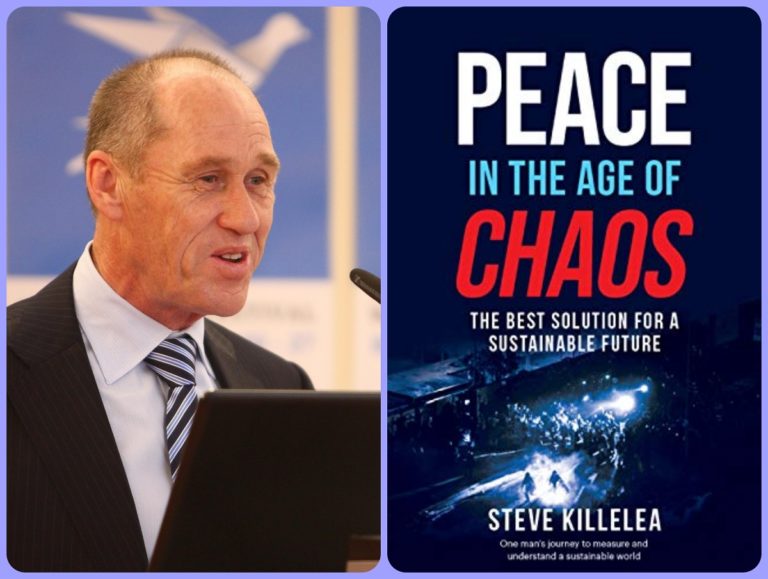

I thought I’d get through Peace in the Age of Chaos: The Best Solution for a Sustainable Future in a matter of hours. Instead, this 272-page book authored by Steve Killelea (published by Hardie Grant, 2020) took me days. I just had to slow down because it was so interesting, not only because Steve recounts his own experience which, in itself, is fascinating, but because I needed the time to absorb all the new ideas. Amazing ideas that you rarely if ever come across elsewhere.

Because this book is a game-changer.

Perhaps I should have expected it. After all, Steve Killelea is recognized as one of the 100 most influential people in the world on reducing armed violence and he is the multi-award-winning founder of the internationally renowned global think tank, the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) whose most famous product is the Global Peace Index. In recognition of Steve’s deep commitment to peace, he has twice been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and won the Luxembourg Peace Prize in 2015.

When you finish the last page and close his book, you’ll never think of peace in the same way again. You thought you knew about peace (I know I did), that it was the reverse of conflict, that it required establishing “security”, that it meant a state of non-violence. Non-violence within the family, the community, the nation, and between nations.

But peace requires much more than that. To achieve real, lasting peace requires addressing a host of factors. And that, as Steve explains in his book (notably in Chapter 5, don’t miss it, it’s a key chapter), means adopting a systems approach. Because what matters is not simply the absence of conflict. You need to go further to achieve real “Positive Peace” as Steve calls it.

Positive Peace is not simply a state of non-violence and you don’t achieve it by controlling violence. In fact, the countries that spend the most on violence-containment and “security” are not the most peaceful countries in the world.

The U.S. is a case in point.

America has more people in jail than any developed country and spends proportionately more on the police and the justice and penitentiary systems than most.

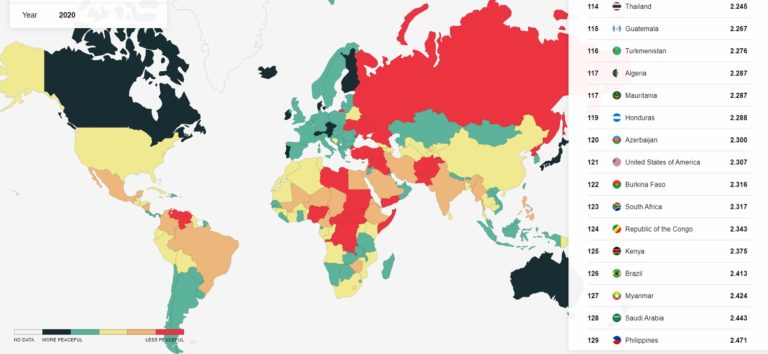

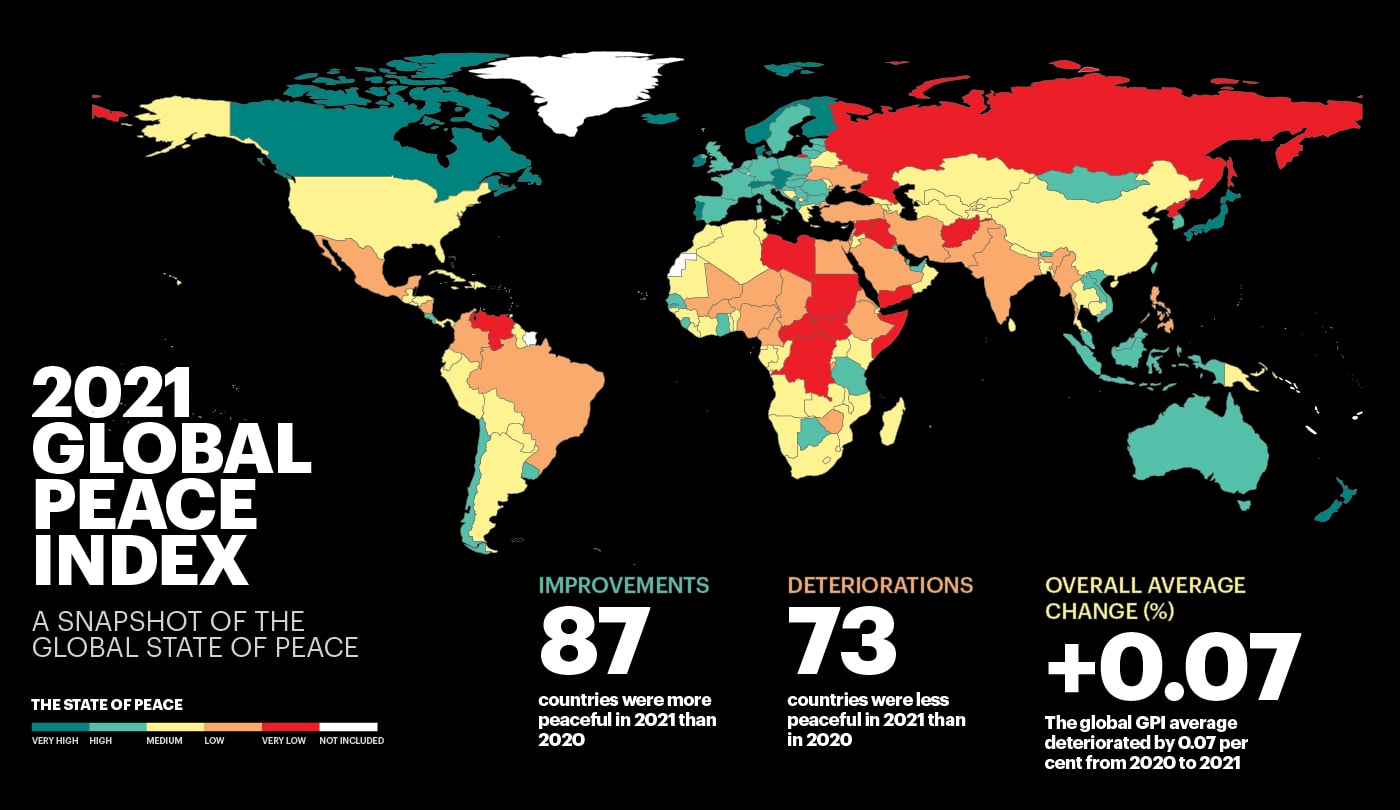

Yet despite all this investment and efforts to contain internal conflict, homicide, and crime, it hasn’t achieved peace. Far from it. In 2020, the U.S. ranked 121st on the Peace Index, a measure of peacefulness in 163 countries (small states with little data are excluded) where the top-ranked country is Iceland, and the last is Afghanistan.

The U.S. comes towards the end of the list, after Azerbaijan and before Burkina Faso, countries that Trump once famously called s***hole countries:

Note that the Global Peace Index is not a marketing trick but the result of serious academic research, a composite index made up of 22 quantitative and qualitative indicators each weighted on a scale of 1-5. The lower the score the more peaceful the country.

So how do you achieve real Positive Peace?

IEP research has unearthed eight sets of factors that they call “pillars”: (1) a well-functioning government; (2) a sound business environment; (3) an equitable distribution of resources; (4) an acceptance of the rights of others; (5) good relations with neighbors; (6) free flow of information; (7) a high level of human capital; and (8) low levels of corruption.

To the extent possible, the pillars should be addressed simultaneously because they are interconnected with numerous back-loops between them – yes, it’s a system. You touch one pillar, the effect travels through them all to varying degrees, depending on their strength.

This systems approach to understanding peace enables a number of deep – and often unexpected – insights into the workings of peace (and war). Insights comforted by big data, giving nuanced views, for example, this one:

📈 While battle deaths have fallen since 2014, the total number of conflicts have increased.

Learn more → https://t.co/aFrKwIYJVF pic.twitter.com/gAZKf7UD5g

— Global Peace Index (@GlobPeaceIndex) January 16, 2021

What is remarkable and confirms the reach of Steve Killelea’s work on peace is that the eight pillars of Positive Peace have been adopted not only by the United Nations, with the support of several UN Secretaries-General, from Kofi Annan to Antonio Guterres, but also by the European Commission (see here) in its policy-making.

I was thrilled to be given the opportunity to talk to Steve and ask him some questions. Here are his answers.

Your book came out in October 2020, a month before the U.S. elections and the upheaval that followed when Trump refused to recognize his defeat. As we now know, the violent reaction from Trump supporters led to a mob attacking the Capitol on 6 January, instigated by Trump himself. Given the low rank of the U.S. on the Peace Index, did you expect something like this?

Steve Killelea: From one angle, the storming of Capitol Hill was unpredictable, as was how far the accusations of voter fraud would be taken. Individual events are very hard to predict, but patterns were in place and patterns can determine trends – and these are far more predictable.

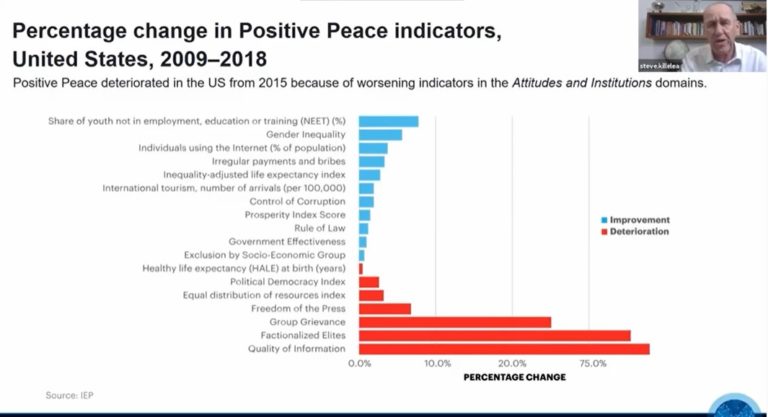

President Trump was elected on the premise he would ‘drain the swamp’, whereas what happened was the opposite: the rich got richer and the poor still struggled. There is a measure of societal resilience called Positive Peace, and in the U.S. it has markedly deteriorated over the last decade. In fact, it has had one of the largest deteriorations in the world.

Some of the factors that have markedly deteriorated are group grievances, perceptions of corruption, fractionalized elites (this is where the elites of societies can’t find common agreement), and political democracy. Given that these factors have been deteriorating, the political unrest we have seen would be expected.

The good news is that the Positive Peace of the U.S. is still high; therefore, with the right policies, it can recover. The real issue for the incoming administration is to tackle wealth inequality and a living wage. If these issues are addressed, then many of the aforementioned problems will dissipate. People who see their lives improving are less likely to feel aggrieved.

That’s very interesting: addressing wealth inequality and guaranteeing a living wage should be therefore Biden’s highest priority. Turning to the world’s current priority issue, COVID-19, you make the interesting observation that countries with “poorer measures of Positive Peace” were less effective in countering the pandemic than those that ranked high. Could you explain this?

S.K.: Again, this goes back to Positive Peace: if we look to the Pillars of Positive Peace, they give us an indication of how well a country may respond. For example, the measure of Well-Functioning Government gives an indication of how well a government may mount a whole-of-government response; similarly, Equitable Distribution of Resources can be viewed through the lens of the public health system because generally the reach and quality of the health system give an indication of how well a country is interested in its citizens. Also, Free Flow of Information: if it is tightly controlled, then people are less likely to trust the government’s comments on how to deal with the pandemic. These are just a few examples. But it is important to realize that Positive Peace works as a system and measures the strength of the system, and as we can see, responses to the pandemic are whole-of-society responses.

Your book is full of surprising insights, you say things people don’t expect to hear. I could cite many examples, but I’d like to bring up this one: You write that violence is not statistically linked to inequalities in health, education or wealth, and that corruption is the overriding problem. Then you go on to illustrate this point with the case of Mexico. There are, of course, many other cases of corruption blocking the way to Positive Peace and one gets a sense that things are getting worse, that the world is sinking into a chasm of corruption, could you comment?

S.K.: This probably needs a little more unpacking as both health and education are very important, and both can be linked to Positive Peace. But focusing on either of these elements without taking into account the whole system may not reduce violence. Both are good initiatives – as an example, just improving education or business on their own is slightly statistically related to higher levels of violence.

However, corruption is corrosive on all sections of society, including peace. Many people see corruption as a moral issue, but I see it primarily as an efficiency issue because it stifles the best outcomes; for example, if the best marks go to the kids whose parents paid the most in tuition fees, then human capital is lost; if government jobs are given to the person who pays the most, then why should they work.

The problem is that pervasive corruption reaches all corners of society, resulting in massive losses of human potential – and the resulting inequities are more likely to lead to violence.

Another surprising insight: You argue that “evolution is more effective than revolution”. Could you expand on the idea here for our readers?

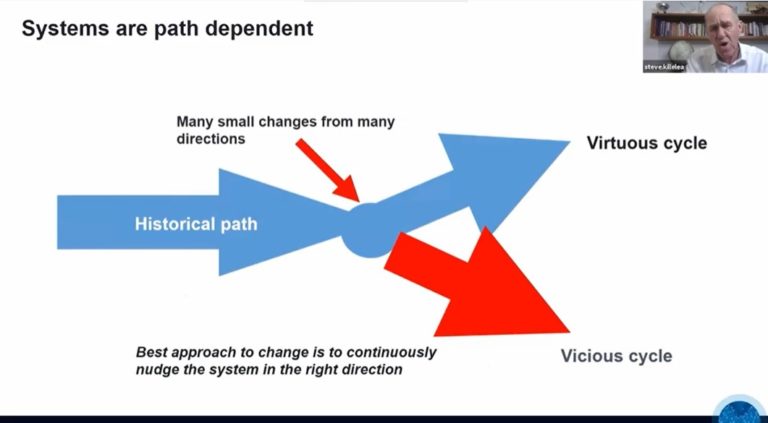

S.K.: There is a concept in systems theory called path dependency, which means that all societies are on a path, and that trajectory is dependent on their past and current values. Some have referred to it as the “march of history”.

Leo Tolstoy said that no one man shapes history; rather, they rise through the conditions surrounding them, and at best can bend them.

If we go into a country and try to radically change it, and the interventions may be good interventions, but run against the local values of that country, they are unlikely to work. Our view of systems is to use many small nudges, and from multiple directions, to change the dynamics of a system.

If a small nudge doesn’t work, then it is recoverable. Think of the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan or NATO’s in Libya. These societies are now in far worse shape than before the interventions.

You hit on the concept of Positive Peace as a result of your work in development aid through your own family’s charity, The Charitable Foundation that has now 3 million beneficiaries, including a remarkable activity: creative therapy for kids through its Be Centre. You recount in your book how you became aware of the foundational role of peace through the tragic story of a young woman you met in Gulu, Northern Uganda, who was the helpless victim of harrowing multi-year violence. That hit a nerve with me as I have worked 25 years in development aid, evaluating projects for FAO. Like you, I found that the most successful projects were those directly responsive to needs and not imposed from the outside; but I missed what you saw (perhaps because, unlike you, I didn’t work on the borders of war): The key role of Positive Peace, without which, aid is destined to fail. Would you, therefore, recommend that the design of aid projects be subjected to the lens of Positive Peace, the way an assessment of a project’s impact on the environment is required prior to approval?

S.K.: Yes, what is profound about Positive Peace is that it is just as applicable at the community level, i.e. a school or a district health project, as it is to the whole of government. The eight Pillars of Positive Peace create the lens through which to view a project systemically.

What I also like is that you can take any developmental project, and not only improve the intervention but also incorporate the concepts of peace in a very practical way.

For example, we trained 500 people from Rotary on Positive Peace in Uganda and one of the clubs had been supporting a school literacy project in a really poor area of the country. They had been at it for about three years without much effect. But a brilliant young man called Jude who had been overseeing the project decided to look at it through the prisms of Positive Peace. The outcome was to nearly triple the attendance at the school and increase the grades by 40% when compared to the rest of the district.

Many of the interventions would not have been done without looking through the Pillars, but the one that stood out was Good Relations with Neighbours… Who would have thought that would be applicable to a school? As it turned out, the kids were raiding the fruit trees in the neighbors’ yards because they were hungry – their parents couldn’t afford to give them food to take to school. Therefore, they planted fruit trees in the schoolyard and provided porridge for lunch, which costs cents. Parents now wanted their kids to go to school as it was one less meal they had to provide. The extra meal at lunchtime meant that their minds were receiving nutriments and they started to become more attentive in the afternoon, which increased their grades.

Looking to the future, what is your next step, what do you see as a priority for yourself and IEP – in short, what issue(s) do you plan (or wish) to tackle?

S.K.: We are currently moving into the juncture between ecological threats, peace, sustainability and development. This we view as a separate challenge to climate change, and although climate change will negatively impact these threats, they exist independently of climate change.

The areas where we are particularly focused are water, food and population growth. Just in Africa alone, there are 17 countries that are likely to more than double their population in the next 30 years. Many of these countries are suffering chronic water shortages and are unstable. Seven of the ten countries with largest increases in terrorism came from this area.

The other area of focus is the application of Positive Peace in conflict areas; for example, we are in the process of training 2,500 people in Ethiopia who will, after training, aim to implement Positive Peace in their country. We are also looking at similar interventions in the DRC and Yemen. The problem is having the funds to actively pursue all the things we would like to do as the demand is there.

Thank you Steve for responding so thoroughly to my questions, I am sure the curiosity of our readers is further awakened. For those interested in acquiring your book Peace in The Age of Chaos: The Best Solution for a Sustainable Future, an exclusive 20 percent discount is available for Impakter readers when visiting www.peaceintheageofchaos.org and entering the promo code IMPAKTER20 upon checkout when ordering the book.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com.In the Featured Image: Steve Killelea in the nomadic area of Samburu in Tanzania, where his charity was installing small dams to better capture water in the wet season for use in the dry season, mainly for livestock. The meeting was held outdoors as there are no buildings in the area; Source: Peaceintheageofchaos.org