Amidst the alarming findings of illegal doping and the political turbulence brewing in the Brazilian capital, reservations toward the 2016 Summer Olympics have often focused on one of the planet’s pesky insects: the mosquito — more specifically, the Aedes aegypti species that carries the Zika virus.

The Zika virus, which is believed to cause birth defects in newborn babies, has been the primary topic of concern for many of the athletes, spectators and journalists who plan to attend the games. Several prominent golfers, including Jason Day and Roy McIlroy, have gone as far as to declare that they would not participate due to the risk of contracting the virus, which is also thought to be sexually transmitted. It was small wonder that just six weeks prior to the opening ceremony, only 70 percent of tickets to the games had been sold, according to CCTV.

But just how dangerous is this disease? Similar to other infamous-but-overhyped viruses, bacteria and “super” bugs, the Zika virus could be just an overblown media story, or in this case, a reason for athletes to instead prepare for their more propitious professional seasons.

As it turns out, Zika remains a serious health concern, albeit a low risk one that shouldn’t deter any athlete, journalist or fan of the games from attending the world’s greatest competitive forum.

About the Virus

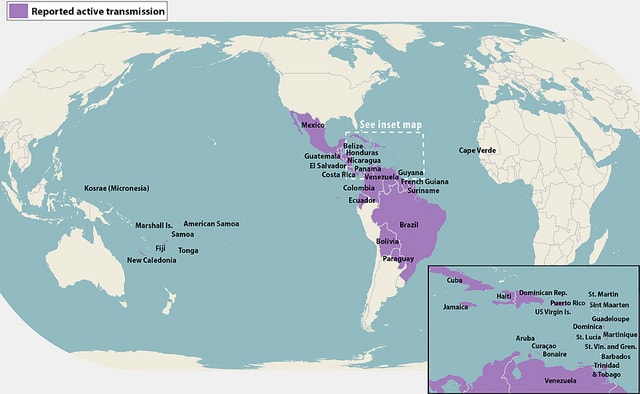

Prior to this year, Zika outbreaks were only reported in Africa, South East Asia and a few Pacific Islands. In May of 2015, however, the Pan American Health Organization confirmed the first outbreak of Zika in Brazil, and the virus has since spread across South America, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Those infected with the Zika virus typically exhibit mild symptoms such as fever, rash and joint or muscle pain. Infection is however potentially dangerous for pregnant women and their offspring, resulting in a plethora of birth defects.

In the Photo: Countries that have active Zika virus transmission as of April 2016.

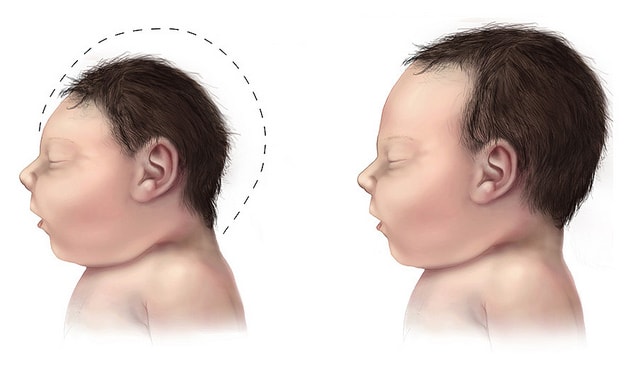

Officially, the CDC cannot confirm that a pregnant woman bitten by an Aedes mosquito would helplessly pass the virus to her fetus. Since May, however, Brazilian authorities have noticed an alarming correlation between the outbreak of Zika and children being born with microcephaly and other severe brain defects. There was also reported to be a rise in infant health problems, including eye defects, hearing loss and stunted growth.

Microcephaly, a condition in which a baby’s head is significantly smaller than normal, appears to be the most distressing of the illnesses reported so far. Images of plump baby bodies supporting smaller-than-normal heads have set media reports covering the upcoming games aflame. At first glance, these reports make it tempting to forgo any upcoming trip to the Latin American country or to even call for the games to be postponed or canceled outright.

Nevertheless, the CDC has been quick to assert that microcephaly can be the result of several other factors. Infections during pregnancy — not necessarily Zika — may cause the birth defect, as well as genetic changes and the mother’s exposure to toxins. One toxin in particular, the pesticide pyriproxyfen, has been reported by some sources to cause microcephaly.

In the Photo: Microcephaly, a condition in which a newborn is born with a smaller-than-normal head, is believed to be linked to the Zika virus. Photo Credit: Brar_J via Flickr.

“Recent media reports have suggested that a pesticide called pyriproxyfen might be linked with microcephaly,” the CDC says on its website. “Pyriproxyfen has been approved for the control of disease-carrying mosquitoes by the World Health Organization. Pyriproxyfen is a registered pesticide in Brazil and other countries, it has been used for decades, and it has not been linked with microcephaly.”

Whether or not the Zika virus is the culprit for so many of these birth defects is unlikely to be determined by the time the Olympic torch is lit.

Response to the Virus

How does one prevent the spread of a mosquito-born infectious disease when half a billion tourists are to descend into a tropical environment for two weeks?

This is the question that Brazilian authorities, the WHO and the scientific community have been wrestling with for the greater part of 2015 with no party having found a one-size-fits-all solution thus far.

Related article: “ZIKA VIRUS HIGHLIGHTS FLAWS IN PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACHES IN THE AMERICAS – PART I“

“First, avoid areas of standing water,” said Brian McNary, vice president of the global risk organization Pinkerton. “We’re talking about mud puddles, slow, sluggish moving rivers, public square fountains that are not really active and aerated. All of these present breeding grounds for the mosquito.”

McNary also suggests the obvious: apply insect repellent and avoid wearing shorts if possible.

In the Photo: Maracana Stadium will host the football competition for the 2016 games in Rio de Janeiro. Photo Credit: Flickr.

It should come as little surprise that even corporations are getting in on this unique marketing opportunity. SC Johnson is using this year’s Olympic games as a platform to promote its OFF! brand of mosquito repellent. In a company statement, SC Johnson announced that it planned to distribute thousands of bottles of repellent to athletes, staff workers and volunteers.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #rio2016

In addition to this commercial beacon of hope, several scientific institutions and organizations have gone further by declaring that the Zika virus is no longer a serious health threat and that the games should go on as planned.

Dr. Karin Nielson, an infectious disease pediatrician at the University of California, Los Angeles working with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, told The New York Times that there were no new cases of the virus reported in Rio de Janeiro since the temperatures started to drop with the fall and winter months. Mosquitos, Nielson said, “run a cycle and are not continuously present.” She ultimately concluded that the virus would not be a problem for the games.

In June, the WHO ultimately agreed with Nielson and other researchers in declaring that the games should go on as planned. The only caveat being, according to officials, is that pregnant women should seriously consider the risks of attending the games. Despite the estimated 500,000 travelers who are expected to visit the Brazil, the WHO has said that this figure is insignificant compared to the aggregate amount of international travel that has already taken occurred to and from the 61 countries where Zika has been reported.

In the Photo: Dr. Margaret Chan at the World Health Organization Opening Ceremony. The organization has determined that the Zika virus should not deter the Olympic games. Photo Credit: Pan American Health Organization.

The Show Must Go On…

Travel warning or not, the Olympic games should and must proceed if for no other reason than to show global unity during a period of relative instability.

For much of the past two years, the media airwaves and internet’s blog-o-spheres have been flooded with horrific reports of terrorist attacks, natural disasters such as super storms and mega earthquakes, and the return of far-right nationalism in politics. While the Olympics is not a panacea to these problems, the quadrennial games are nonetheless a strong, albeit brief, light of hope that reminds us that humanity is capable of coming together despite differences in political ideologies, faith or race.

One pesky mosquito breed should not deter such a cherished tradition.

Recommended reading: “RIO 2016 OLYMPICS: FROM THE ATHLETES’ VILLAGE TO ZIKA – JUST HOW READY IS BRAZIL?“

_ _