Marcus Bleasdale is a photographer who has been documenting some of the world’s most brutal wars over the past eighteen years. Marcus covered the wars in Sierra Leone, Liberia, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Somalia, Chad and Darfur, Kashmir and Georgia.

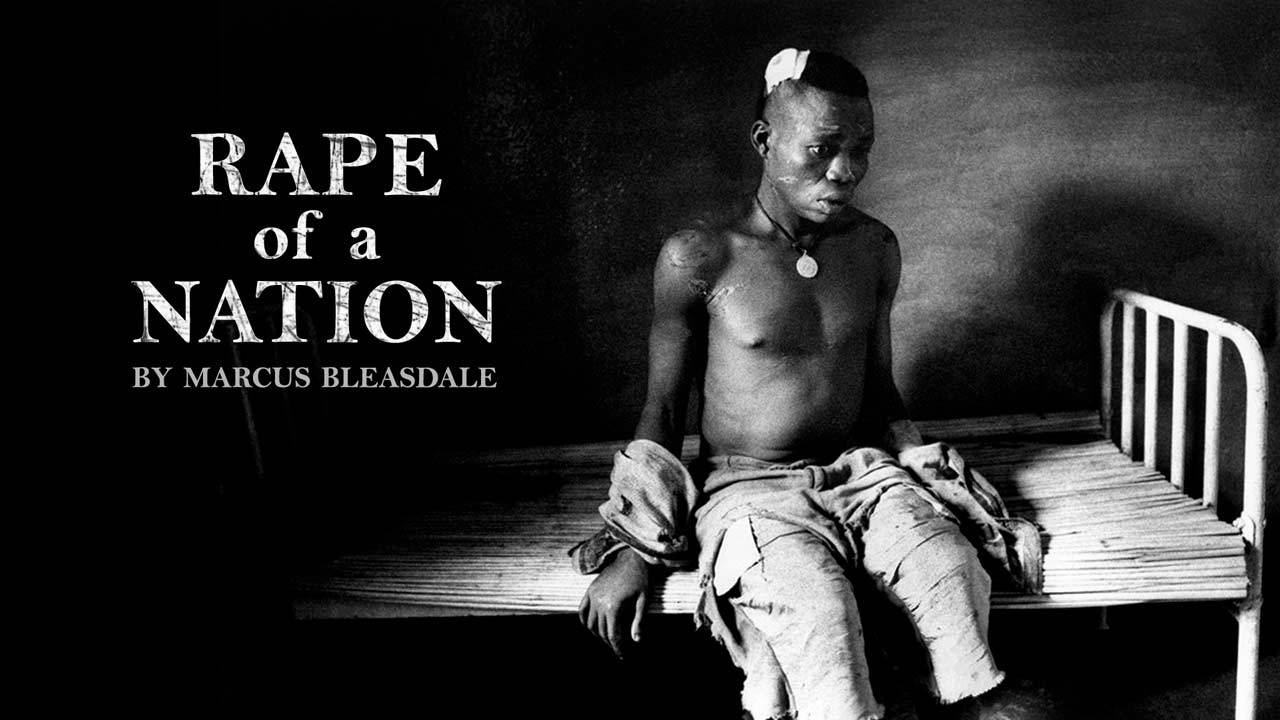

Marcus documents human right issues for Human Right Watch, photographs for National Geographic Magazine and has published three books: “One Hundred Years of Darkness.”(2002), “The Rape of a Nation” (2009), and “Unravelling” (2015).

Impakter Magazine: When did you discover your passion for photography?

Marcus Bleasdale: The reason I do what I do is not because of the photography; it is because of the human rights issues, which I focus on. I use photography to highlight them and engage people. It is the issue that comes first and not so much the photography.

When did you discover your interest in documenting human rights issues? What was the trigger?

M.B.: I left the finance world, I think, in 1998 or 1999 and then I went to cover events in the conflict in Kosovo. That’s how I began to understand the impact that conflict has on humanity and engage at a greater level of the issue of conflict.

After Kosovo, I went to cover the conflict in Sierra Leone, and that started my engagement with the issues around minerals and the use of minerals and how they engaged and financed conflicts, and I have been working on that for the last 20 years.

A child soldier of the Mai Mai in Kanyabayonga during an offensive against the CNDP

How do you find the courage to go to such dangerous places?

M.B.: I did not think about it in terms of risk so much. I think about it that it’s an issue that’s normally quite underreported and it is an issue that I want to work out.

When you come back from the conflict areas, what lessons do you take with you?

M.B.: It depends on the conflict. I think that conflict focuses on natural resources and focuses by on buying natural resources. What I take away from it is that we are all very engaged and implicated in conflicts like that. We, as consumers, are engaged in financing that conflict, and it is up to us, as consumers, to be aware of the impact we have with our purchases and with our engagement.

That´s what I take away from those sorts of conflicts. The life is quite more complicated, and because it won’t necessarily about conflict minerals, it was about injustice, social injustice in bad governance, and it took a long time for the world to understand motivations on that particular conflict.

The conflicts are very complex. They and their motivations change over time. So what I take away from them initially is that the dynamics of the conflict changes over time.

Another lesson from the conflict I learned is that you have to investigate the conflict, why does it exist and why it is occurring, by yourself. It is often the case, that the reasons for this conflict are much more complex than we initially think.

The burial of of eight-month old Alexandrine Kabitsebangumi, who died from cholera, in Kibati, north of Goma in eastern Congo.

You document human rights issues. You are concerned with human dignity and the value of human life. How do you feel your message can best be transmitted?

M.B.: In my opinion, you need to use many different mediums. I think photography is an important part of showing what conflict and human rights abuse is.

I also believe that it is essential to have a very engaged and defined legal framework. Working with human rights lawyers, advocacy groups like Human Rights Watch or Project for Amnesty International is also very important because those organizations work in a more diplomatic level.

So I think it is a complementary relationship between those two. I also believe that social media has a crucial role to play, whether it is Instagram, Twitter or Facebook.

It is increasingly important to make the messages that we are trying to get people understand are widely available and understandable. Social media is a fantastic tool to let that happen. We need to use many different instruments to make the most impactful communication strategy possible.

You wrote very impactful books like “One Hundred Years of Darkness”, “The Rape of a Nation”, “Unravelling”. Can you please tell more about them? What is the purpose of those books?

M.B.: I think that’s changed over time. When my first book came out in 2002, there was no such thing as social media. There was the Internet, but it was quite fledgling and was not very easy to use.

Within the world of photography, if you have a very subtle and sophisticated message, the use the books was essential, in a way, to get a particular message that you had. It would engage a very selective audience, but it would be a culmination of a larger body of work which sits on different platforms, and this book is just one of those platforms.

What’s the best tool to engage in human rights? A book is another tool to engage the world with your ideas, and communication tools have become more effective, and the concept of a photography book and how people use it, has also changed.

The last book that I published was “The Unraveling”. It is focusing on the conflict in the Central African Republic. In this book, three essays are written by humans rights lawyers, and one essay is written by Nicholas Kristof from the New York Times and these essays show a different side of the conflict from the photography and they engage the reader in a different way.

That purpose of the book was trying to work together with a human rights publishing organization, to spread the message wide. The organization, called Photo Evidence, published my book, and this organization focuses on many different human right issues around the world, and they wanted to highlight this particular issue, so I worked together with them.

Another project is “Rape of Nation.” I had been working on it over nine years, and it is an ongoing process. I continued working on the issues of Democratic Republic of the Congo, but I thought that it was better to put together a whole body of work and show it eloquently so that people could in some way to understand what was happening in Democratic Republic of the Congo in a very concise way.

That book was about saying, “This is happening now” and “ you should focus on it now”, but it is not to say that I would not continue to work in Congo on that issue. I did and still do.

That book was very effective in engaging lawmakers. We had an exhibition in the United Nations, in the Houses of Parliament and the US Congress. We handed copies of the book to different senators and to different congressman and women. So it was a way in which we could engage with the establishment to try to get them to change their work and practices.

Can you tell about challenges that you faced as a documentary photographer and how did you handle them?

M.B.: Challenges? I think every job has its challenges, but I think along the way, you have them, for example, in production. You have challenges where you have to fight against government officials, or rebel groups, or the concept of security within these areas during the conflict. All of these things create challenges on the way you create your work.

Security is one of the key ones, of course. You have to stay safe. But there are also government officials who don’t want you to do the work that you do, and they try to put obstacles in the way. Of course, you have to navigate through those so you can access the places and tell a story in the most effective way.

But then, once you’ve created the work, and you have the production, then what do you do with it? You still have to get people to see it and understand it, and react to it and engage with it, and of course, you want them to become as passionate as you are about the issues. So, the most important thing is to communicate these things to increase the followers in your cause.

You can face challenges along the way in different forms in different ways. Never give up. That’s the motto at the end of all of that.

A young miner “Olivier” works with other miners in the mining town of Pluto in Ituri Province to extract rock and sand from a large pit which has taken over a year to excavate. The miners are made up of many different people from all over Congo who come to seek their fortune.

You have a lot of awards. Do you have any advice for aspiring photographers who start their way in this field?

M.B.: I think the most important thing for a photographer is to be passionate about what you are photographing. The most impactful photography is photography that tries to educate and engage us in a further understanding. As a photographer, try to become an expert in the field you are documenting. Only then can you be taken seriously.

Conflict is extraordinarily complex and nuanced, and it is not something anyone can really understand in a short period of time. So you really have to study it, you have to understand it and understand the people, and the culture, and the history, and the concept of governance in those areas to really understand, why conflicts exist in a particular place.

Then, once you have that level of understanding, you actually start to photograph in a legitimate way of asking people to listen and see what it is that you are trying to address.

If you are not very knowledgeable or thoughtful about the particular issue or part of the world, why should anyone listen to you or see your work?

If you want to study photography and if you really want to become a photographer, then I think you should study history, politics or international relations. Then you can actually formulate an opinion about the world around you with that knowledge, and you can use the camera as a tool.

Besides documenting human rights, you have a family and were studying at Cambridge University. How do you find time for all of those things?

M.B.: That’s a good question. I don’t have time for all of it, but I try to make it happen. Speaking about photography, I try to choose particular issues, so I don’t photograph all day, every day. I usually choose two issues a year which I want to focus on. It takes a lot of time to study them and become an expert.

Sometimes all of these things overlap. For example, my study at Cambridge University overlapped with the work I was accomplishing with National Geographic magazine and Human Rights Watch. And so they complemented each other in a way.

Elvis, a child working in the mine overseen by ex-Seleka soldiers at the Ndassima Gold mine previously run by the Canadian Company AxMin. It was abandoned by them in 2012 when the Seleka came into the country. The Seleka immediately took control and started to mine. They take 15% of all gold mined in the region from local miners. One thousand three hundred miners work around this mine.

What are your plans for future projects?

M.B.: Yes, I am currently researching a few different projects, and when I get a deeper understanding of what I want to say about, then I’ll start something new, but I am still not quite finished on the Central African Republic or Congo projects. I don’t think if I ever will finish them, I think those two projects will continue with me for many years, so I am still working on them and documenting.

All photo credit to Marcus Bleasdale