The UN estimates that 1.3 billion tons of food is wasted every year, a third of the world’s total production. According to the IPCC, the loss and waste of food was responsible for 8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions between 2010 and 2016. Food waste also leads to a waste of the resources (water, energy, labour, capital and land) used to grow, transport and package the food. The FAO estimates that food loss and waste costs developed nations USD $680 billion and developing nations $310 billion annually.

A graph showing the waste per person per year in kgs by region (Source: FAO).

While developed and developing countries waste similar quantities of food (650 million tonnes per year), in developing countries, 40% of the losses occur at the post-harvest and processing stages, while in developed countries, 40% of the losses occur at the retail and consumer levels. Solutions depend on the stage these losses occur at; for example, developed countries need to focus on better retail practices and changing consumer behaviour, while developing countries need to focus on improving storage and distribution infrastructure as well as providing financial and technical support for better harvesting techniques.

A number of innovative solutions already exist for countries looking to tackle food waste. In a joint collaboration with the company Too Good To Go, Unilever, Arla Foods and Carlsberg have added a new packaging label, ‘often good after’ directly after the ‘best-before date’ on certain foods to inform consumers about expiry dates versus best-before dates. The latter is meant to be an indicative measure requiring consumers to judge whether food is expired based on sight and smell. This new practice is being launched in the Nordics and will expand to other markets provided legislation allows it.

Technology in Papua New Guinea is being used to help local farmers’ livestock meet internationally-recognised standards. A digital tracking system helps verify important information about pigs like pedigree and what food and medicines they have been fed, giving importers and consumers greater purchasing confidence and reducing the risk of food being rejected and disposed of. This digital system was designed by the FAO and the International Telecommunications Unit (ITU); the broadband network is being improved locally so that farmers can update records easily on their subsidised phones.

Insignia Technologies has colour-changing tags that can be applied to products at the point of manufacture. The time-temperature indicators change the colour of the label according to the shelf life of the product, allowing restaurants to prioritise products that are about to get spoilt, thus reducing waste.

UK academics are developing paper-based, smartphone-linked spoilage sensors for meat and fish packaging. They cost less than £0.02 each and are non-toxic and biodegradable, helping to detect spoilage and reduce food waste for supermarkets and consumers.

Global food waste initiative Winnow has developed software that tracks food being thrown away in kitchens. By using this software, businesses can record what’s being thrown away, assess the cost of the discarded food and get a detailed breakdown of each day’s waste to better manage their menus and reduce waste.

Government interventions to reduce food loss and waste could include providing incentives or financial aid to smaller farmers and producers so that they can adopt more efficient techniques and practices. Organisations like the World Food Program help small farmers connect to people in need and also provide the necessary technologies for more efficient storage and distribution to prevent spoilage.

Local governments can support the set up of organisations like the Waste and Resources Action Program (WRAP) in the UK that develops actions and milestones to help UK retailers and brands halve food waste by 2030. It provides guidance on labelling, packaging and storage and conducts and publishes surveys of businesses on their progress.

Updating legislation around labelling requirements so that the best-before and use-by dates are clearer to consumers, as well as ensuring solutions like the ‘often good after’ concept is brought in to markets, will also help.

Governments should also educate consumers on reducing food waste. The highest carbon footprint of wastage occurs at the consumption phase (37% of total), whereas consumption accounts for 22% of total food wastage; one kilogram of food that is wasted further along the supply chain will have a higher carbon intensity than at earlier stages.

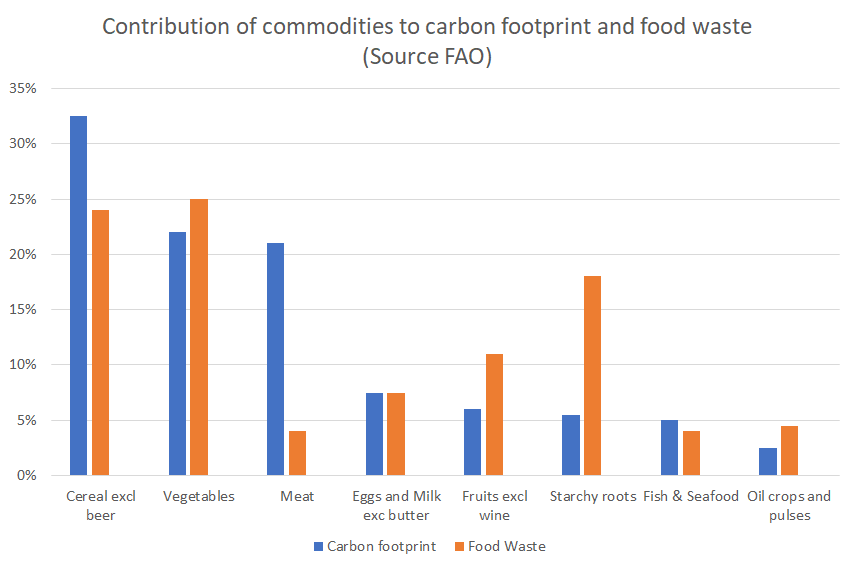

A graph showing the contribution of commodities to carbon footprint and food waste (Source: FAO).

Cereals, vegetables and meats have intense carbon footprints and contribute heavily to food waste. It is vital to, in the case of meat, minimise consumption, while for cereals and vegetables, optimise how they are managed and consumed to reduce wastage.

Project Drawdown, a global research organisation that identifies, reviews and analyses the most viable solutions to the climate crisis, ranked solutions to global warming and found that cutting down on food waste could have a similar impact on reducing emissions over the next three decades as onshore wind turbines. If small and large businesses, governments and consumers work together, about 70 billion tons of greenhouse gases can be prevented from being released into the atmosphere.