Project HOPE is a 60-year-old global health development and humanitarian non-profit organization whose mission is to empower health workers to better care for the people they serve. We currently work in 29 countries building individuals’ local capacity to effectively confront global health challenges, such as infectious disease threats, non-communicable diseases that are spiraling out of control, preventable causes of maternal, newborn and child mortality, and the myriad of health needs that emerge from disasters and emergencies, both natural and man-made. Domestically, we also lead rigorous health policy analysis through our influential journal publication, Health Affairs to stimulate a non-partisan, evidence-based national debate for making the best decisions to improve health outcomes in the United States and elsewhere.

Project HOPE’s mission and work are aligned with the global blueprint for health that the UN’s 2018 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs) provides.

But why should the Millennial Generation be interested in these goals?

Personal Impact

The first reason is that most of us will eventually discover how health inevitably becomes deeply personal and important to us all. By the 2030 target date for achieving the SDGs, Millennials themselves will have reached middle age and, therefore, be more likely to have seen their own parents, relatives and friends experience declining health as they age. They may have had children or grandchildren of their own. Perhaps they will have experienced cancer, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes. Maybe they were exposed to a serious infectious disease, or worse. They’ve probably experienced the public health effects of escalating climate change—whatever those may be.

Compassion

The second reason is that achieving the health SDGs is about our own humanity; it is simply the right thing to do. While tremendous progress has been made in global health over the past 20 years and we should acknowledge and celebrate that, the daily death toll from largely preventable and treatable causes of death remains truly staggering and senseless.

Every day:

- 830 women die from pregnancy and childbirth;

- 15,000 children under five years of age die, including 7,000 newborn babies;

- 3,800 people die from TB (a curable disease);

- 3,300 people die from HIV (also treatable);

- And last but not least, there are 41,000 deaths in those under 70 years of age from non-communicable diseases.

But the health SDGs are about more than just preventing deaths—they are also about advancing wellbeing, which could be described as how we feel about ourselves, our own lives and those of our loved ones.

Economics

And finally, there are several other positive spin-offs that could be realized during the course of working to achieve the health SDGs. While economic development is good for health by raising living standards, scaling up health systems in order to accomplish the SDGs is also good for economic development. In addition to healthier workers being more productive, the health sector itself can be a leading contributor to GDP as a major driver of technology and innovation, job creation and business development. The returns on investment in health are estimated to be 9 to 1. In financial terms, the size of the health sector globally is currently valued at over $5.8 trillion annually. The growing demand for healthcare jobs and workers is expected to create an additional 40 million new jobs in the global health sector by 2030. With 66 percent of health workers worldwide being women, job creation in the health sector is also good for empowering women around the world to be in a better position to manage their own economic status.

Barriers to Achieving the Goals

The health SDGs are indeed ambitious. The grim reality is that there are reasons to believe that we may not be on track to achieve these goals in numerous places around the world over the next 11 years. For one thing, leadership is lacking, particularly in failed states, to drive an effective multi-sectoral response, including at the community level where concerns tend to be more about daily survival. For example, two-thirds of global maternal deaths occur in countries affected by a humanitarian crisis or fragile conditions. Moreover, the global multilateral system aimed at supporting countries in their health development is fragmented across 11 sometimes competing agencies. Sustainable financing also remains an obstacle, but the recent commitment of African heads of state to increase financing for health is a positive sign.

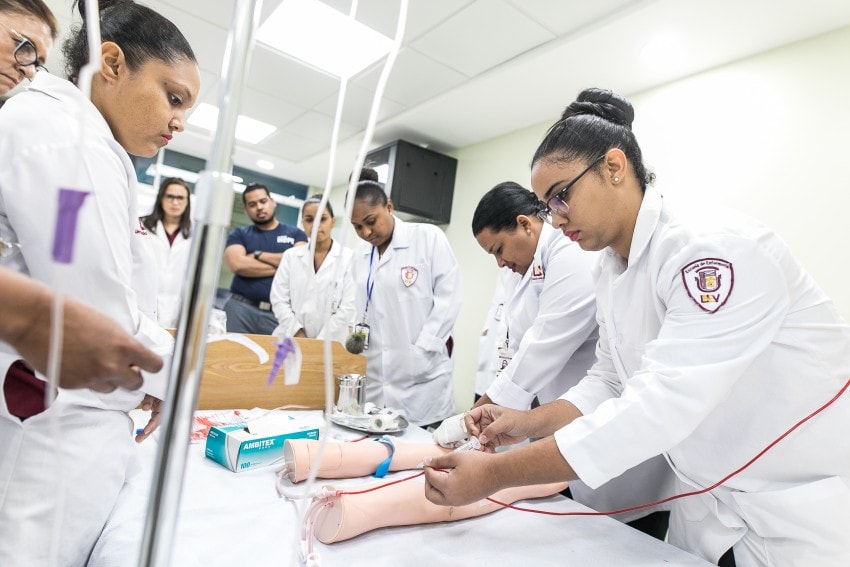

In our experience, weak health care systems remain the biggest barriers to achieving the health SDGs, particularly at the primary care level, which includes the most basic preventive and curative services. Furthermore, the health care worker component remains the weakest aspect of the health care system. None of the other health care system components—finance, information systems, research and development, supply chain, infrastructure, policy and guidelines, service delivery, etc.—can deliver life-saving services if the workforce is inadequate.

But this is not new news. The global health workforce has been in crisis mode for decades. The World Health Organization has been warning the world about this crisis, yet the world has simply failed to act. Numerous well-meaning health initiatives led by governments, multilateral agencies, corporations and foundations are making laudable progress with specific diseases, including HIV, TB, malaria and maternal and child health. However, not a single global health initiative exists to sufficiently and rapidly scale up the education and training of new health workers.

The challenges of shaping the global health care workforce are multifaceted and there is no silver bullet. To begin, we face a global supply and distribution problem. There are simply not enough health care workers to meet the demand, particularly in Africa, and the shortfall is projected to continue, thereby causing increased global competition for the few workers that do remain. Fortunately, 40 million new jobs in health care could be introduced by 2030 through the fulfillment of the health SDGs. However, projections esteem that we will fall short by 18 million new workers, largely due to global population expansion—especially that of the elderly—outpacing health care worker production.

Strong leadership has also been shown to yield results. From 2004 to 2010, the Government of Malawi increased the health care workforce by 53 percent across 11 priority cadres. Ethiopia rolled out 35,000 new health care extension workers to provide primary health care services at the community level from 2005 to 2010. Improvements in secondary and university education in the sciences must also accompany increased production in order to prevent high failure rates in medical and nursing schools.

Even with more graduates, substantial urban to rural disparities exist. 50 percent of the world’s population lives in rural areas, yet 75 percent of doctors and 62 percent of nurses serve only urban populations. Some countries like Zambia have even offered pay and other incentives such as housing for health care workers to serve in more rural areas.

There are also qualitative aspects to consider in order for the health care workforce to help achieve the SDGs. One primary concern has to do with the quality of care delivered when health care workers are demoralized by poor salaries, poor and dangerous work conditions, a lack of career structure, a heavy workload, and a lack of medicine and equipment.

The composition of the workforce needs to meet certain requirements in order to address local health priorities. Firstly, frontline health care workers must be available in sufficient supply so as to provide the local population with adequate primary health care services. Frontline workers include those closest to the general population, such as community health workers, midwives, clinical officers, general practitioners, pharmacists, nurses—the backbone of the health care system—and laboratory technicians amongst others.

Secondly, effective policies, training and mentoring need to be put in place in order to permit the task-shifting of services—the delegation of certain medical responsibilities to less specialized health workers—to frontline health care workers, who can thereby provide a wide range of lifesaving intervention procedures. A system, such as a Medical Facilities Management Systems, can also be implemented in order to effectively handle the center and to allow better efficiency for the healthcare workers. If implemented correctly, task-shifting has been shown to be quite effective in safely providing needed access to services that would have otherwise been unavailable to patients in need.

Widely successful examples of task-shifting include:

- empowering nurses to initiate TB treatment and antiretroviral therapy for HIV;

- community health workers prescribing antibiotics for pneumonia and antimalarial drugs;

- HIV testing by lay counselors; HIV self-testing;

- and caesarean sections and emergency surgery performed by clinical officers when there are no doctors or surgeons available.

But frontline health care workers cannot do it alone. Their credibility suffers if they are not supported up by an effective referral system providing higher specialized levels of care to deal with more complex and life-threatening conditions. If a community is motivated to deliver babies in a health facility, but then finds that there is no delivery room space or that midwifery service or adequate medical supplies are unavailable, their trust is broken.

In addition to a clinical workforce that has experience with diseases such as Ebola, HIV, TB and so forth, it is also a priority to put in place a complementary public health care workforce, including frontline surveillance officers to detect disease outbreaks and track other public health issues. Other professions include epidemiologists, statisticians, vaccinators, logisticians, laboratory personnel, and program managers.

If action is not taken, the uncertainties over the next 11 years will negatively impact the ability of health care workers to drive progress towards achieving the 2030 health SDGs. Global economic trends will affect local economies and their ability to finance the health care system. Failed states will continue to have difficulty with health care worker production and retention and service delivery to growing populations of the most vulnerable.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Moving Outside of Policy Pigeonholes to Improve Global Health”

“Health and the SDGs in a Real World Setting”

Aging populations will increase the demand for certain health care workers and stimulate their migration from low and middle-income countries to high-income countries. Nationalistic tendencies may have the opposite effect on migration. Climate change will not only affect disease patterns, but also increase the migration of health care workers along with others who are able to migrate, leaving behind even weaker health care systems to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged populations.

Ultimately it will require sustained political will at the highest level if countries are to convert their commitments to the SDGs for health into tangible actions and results. The evidence is clear that the return on investment in health care workers is highly favorable for the future of economic and social development. We all have a role to play in making this happen. But Millennials themselves have the most at stake in this scenario, and the world awaits their turn to make a difference by providing leadership, taking ownership, and getting involved.