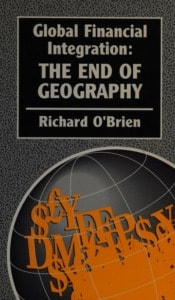

We live in a world that is shrinking day by day. Globalization now rules the day, signaling ‘the end of geography’, as economist Richard O’Brien strikingly said in his bestselling book, Global Financial Integration: The End of Geography.

Published some 30 years ago (in 1992), this is a stark reminder of how long the phenomenon of globalization had already been going on even at that time: At least since the early 1980s, when the term globalization first became popular and nationalism emerged with a new found glory as the alternative.

Richard O’Brien’s explanation of globalization as the result of the new, more efficient communication and transport technologies that interconnect all the locations on the world map is now the way we all understand the phenomenon. Popular culture entered the fray to reveal another dimension: Globalization is ending the tyranny of distance as television, films, advertising, records, clothes, modes of transport etc, push out new consumer products to ever larger markets. Pizza, once the trademark product of small bakers in Naples, becomes mass-produced and looks nearly indistinguishable from Germany to Japan; but the fact that it is a worldwide sensation is undeniable.

The question, then, is how to make this excessively connected world work for the multitudes of people on this planet.

For this, we first need to realize the nature of globalization as the organizing phenomenon of today’s world. It is thought to be strengthening the control of an advanced capitalist system (hence its so-called “neo-liberal roots“), replacing the domination of the nation-state with transnational corporations, and challenging local traditions through a global culture.

The fact remains that while everyone talks about globalization, they mean different things that have totally different fallouts! In brief, we come across the following definitions:

- A network society: Manuel Castells, a world-renowned sociologist, revises his theory in his article, ‘The Network Society Revisited’ published in 2022, to define globalization as a firmly information technology-based event, and update the economic and social aspects of the information age.

- A network for increasing human rights: Leslie Sklair, the current President of the Global Studies Association, presents almost an opposite picture to the capitalist utilization of the network by proposing the globalization of human rights in his much acclaimed book, Globalization: Capitalism and its Alternatives that came out in 2002.

- A clash of cultures: Samuel Huntington, an influential political scientist, describes globalization as a cultural collapse in his powerful but much debated book on the post-Cold War global politics, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, which was originally published in 1996. Huntington does not suggest why different cultures must clash when they come in contact with each other. Really, why can’t they just borrow from each other?

- An opportunity for transcultural experience: Allan Luke and Carmen Luke, established scholars of sociology and policy, write in their book chapter, ‘A Situated Perspective on Cultural Globalization’, that a careful observation of how local forces negotiate the global trends will lead to an improved understanding of the current motivations for thought and action.

Therefore, it is clear that both the positive and negative aspects of globalization have come to the fore. To put it differently, globalization initiates a contradictory order through which a popular culture circulates the globe, apparently creating sameness everywhere although it does something more: It encourages through the local and global exchanges the rise of mixed cultural practices. This approach has a broad appeal, and yet remains grounded in local lore and customs.

Globalization and the paradox of the good and the bad effects

The new technologies can and do worsen existing inequalities regarding class, gender, race, and local power structures, which allows transnational alliances to advance their interests.

Political Science researchers Clare Cummings and Tam O’Neil point out in their UK government report in 2015 that ‘Women’s access to, and use of, digital ICTs can challenge gender-based power relations. This can provoke a backlash, including in ways that increase women and girls’ insecurity and subordination’.

Tim Unwin, the UNESCO Chair in ICT for Development and Emeritus Professor of Geography at the University of London, writes in his poignant article, ‘Can digital technologies really be used to reduce inequalities?’ published in 2019, that ICTs ‘have transformed the lives of many people living in poorer countries. At the same time, there is no denying that they have also greatly increased the economic power and wealth of the owners and shareholders of large global technology corporations:

It remains true, however, that a renewed interconnection among grassroots movements is able to exert pressure on transnational corporations and broadcasting media for reform regarding their corporate policies so that a greater democracy is achieved at a local level.

Media Studies scholars Dorothy Kidd and Clemencia Rodriguez highlight the positive impacts of radio, video, film, and Internet initiatives in various parts of the world through their introductory chapter for Making Our Media: Global Initiatives Toward a Democratic Public Sphere (2009). They strongly believe that ‘Grassroots media have grown from a set of small and isolated experiments to a complex of networks of participatory communications that are integral to local, national, and transnational projects of social change, as well as to campaigns to transform all aspects of information and communications systems.’

As proliferating media and the Internet generate a greater awareness regarding the grassroots struggle for democracy, new solidarities can be formed for making corporate-elites listen to the local/regional concerns.

For example, the ‘Arab Spring’ during the 2010s has been explained as a regional response to the challenges of globalisation. Indeed, the ‘Arab Spring’ exemplifies how the local forces demonstrate aspirations towards promoting democratization and social justice. As the new technologies become ever more crucial for maintaining everyday life, developing a resisting ‘technopolitics’ as described by theorist of media culture Douglas Kellner in Technology and Democracy: Toward A Critical Theory of Digital Technologies, Technopolitics, and Technocapitalism (2021) becomes increasingly significant.

Clearly, corporations and state apparatuses are generally not going to prioritize progressive social changes. As we know, not all nation-states are by definition welfare states, where the state takes responsibility for the universal welfare for its citizens, and social protection is often delivered to them by a combination of government, and non-government services. At any rate, there has to be a constant pressure on corporations and state apparatuses from citizens worldwide to create a new politics, so to speak, for accommodating demands for more education, well-being, and human rights.

Due to the fact that popular culture has the power to raise awareness about significant social issues like discrimination and environmental concerns, sparking discussions and positive changes, we have to explore how local and global forces shape the production and consumption of popular culture.

In other words, the sphere of popular culture cannot remain completely detached from geopolitics. In fact, scholar of geopolitics and security studies Klaus Dodds introduces a term called, ‘Popular geopolitics,’ in his book, Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction (2019), by highlighting the interconnection between popular culture and geopolitics and explaining how this is well-served by blogging and podcasting, for example.

As a multidimensional sphere, the cultural production here responds to domestic and international politics, global economics, and socially situated identities of the consumers.

Once again, imagining popular culture with a uniform appearance will lead to wrong ends. Likewise, the term ‘the people’ cannot refer to a single group within a society, a country and the globe. On the contrary, social groups can be distinguished economically, politically and culturally.

Nevertheless, they are potentially capable of being united thus proving the fact that human beings create cultural artifacts like books, magazines, television programs, advertisements, movies, and music, and are in turn shaped by these cultural matters.

Therefore, popular culture may or may not uphold a politics of resistance; may or may not be created by subjugated people; and more importantly, may or may not serve the economic interests of the dominant class. However, this does not mean that popular culture cannot be utilized as a platform for advancing basic human values.

Whether or not popular culture – from fashion to digital activism and aesthetic labour (https://vanessadirienzo.home.blog/what-is-aesthetic-labour/) – will embrace egalitarian worldviews depends on the socio-political leadership of a society. If the leaders are willing to strive for improving social systems then it would be all for the better.

Nationalism in the Age of Globalized Systems

If social systems can come under the influence of globalized forces of thought and action, we have to think about the relevance of nationalism in this context. As people are exposed to higher levels of information exchanges, they tend to be less inclined to show excessive loyalty to their home nation. The question that needs to be asked is whether detachment from traditional values and tolerance for foreign influences make nationalism and globalization contradictory forces.

If we think that the coexistence of these entities means that a war of value will inevitably ensue from which only one side will emerge victorious, we will forget about the core of nationalism. Surely, nationalism values the unified identity of citizens and autonomy of nation-states, whereas globalization values the economic interdependence of people and organizations across national borders.

Having said that, the essence of nationalism consists of a people’s motivation for not only preserving but also enhancing their own culture, tradition, and identity, rather than simply seizing state power. Why should a nation strive to be free from outside control, if at the same time it does not aim for supporting progress and prosperity for its people?

If this is the prime objective of existing as a nation in contemporary times, it will be sensible for national communities not to mount a backlash against globalization. Undoubtedly, globalization can introduce unknown risks for national communities whose existence depends on cultural cohesion.

But globalization also has a positive side.

As a result, a complete disengagement from globalization suggests two possible outcomes for today’s nations: (1) they have to be labelled as a source of fragmentation across the globe, or, (2) romanticized as a defender of cultural unity.

Neither is a viable option in the era of globalization.

It is no secret that in the name of cultural unity, nationalism can undermine the nation-state’s international relations, its status on the world scene as a member of the global polity. This can happen for example, when nationalistic impulses push leaders to ignore human rights conventions the country has already subscribed to. Therefore, nationalists need to decide what aims to pursue. They should be aware that pushing for a distinct identity comes with definite drawbacks, foregoing some very real benefits from globalization. There is a price to pay for extreme nationalism, and the stronger the rejection of globalization, the higher the price.

In the end, the dynamics between nationalism and globalization should remain realistic so that the challenges of globalization do not outweigh its benefits. Nationalists should not forget that these benefits mean ensuring renewed vigour and elevation for the national community. A win-win for nationalists if they play their game right.

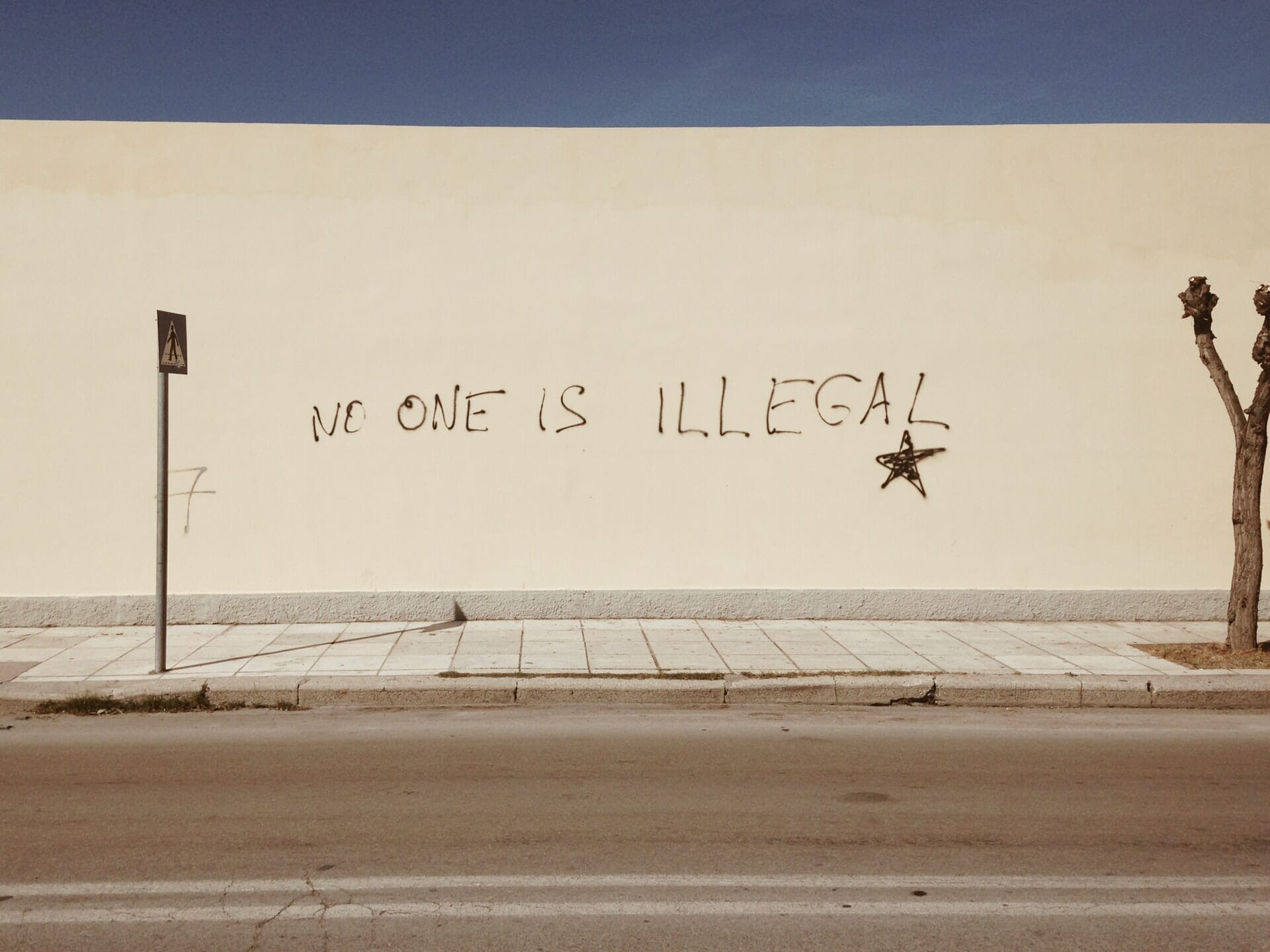

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Protest in Washington by Ted Eytan from NIAC. Featured Photo Source: Policy Watcher, “Beyond the End of History.”