Every time I explain the research I do, I inevitably frame it as “soccer and politics,” or even more broadly, “sports and politics.” I have learned that absolutely everyone will have an opinion on these topics. Some might mention the corruption scandals surrounding FIFA. Others might bring up the NFL “Take a Knee” movement led by Colin Kaepernick or something about the World Cup or Olympics that was recently on the news. Nonetheless, at the end of the day, everyone has something to say about sports and politics.

These two topics are undeniably linked. It is no coincidence that political actors often use sport metaphors in politics. Barack Obama once explained U.S. foreign policy by saying, “You hit singles, you hit doubles; every once in a while, we may be able to hit a home run,” referring to baseball. John F. Kennedy once said, “Politics is like football: if you see daylight, go through the hole.” Sports are more than forms of entertainment. They are also spaces in which many relationships of power are produced and reproduced, including those involving gender.

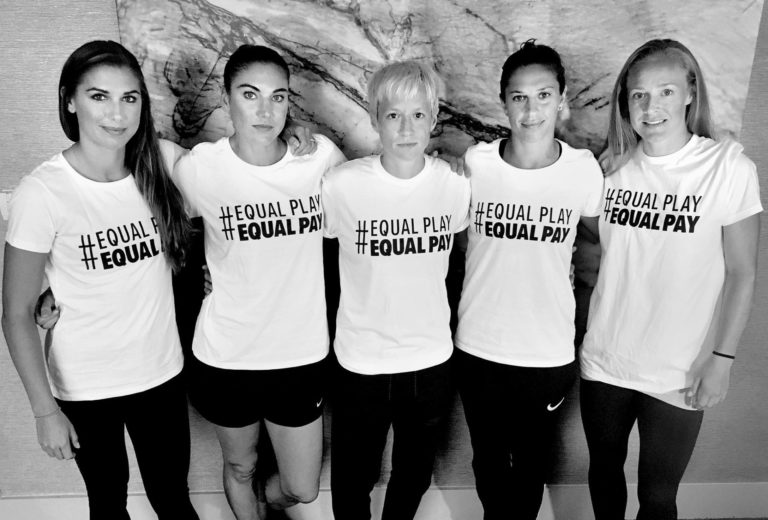

Sometimes, I add “gender” or “feminist” to the explanation of my research, and I hear about women players getting paid less than men or that people enjoy watching men’s soccer much more than women’s soccer. Back in July, after winning the World Cup for the fourth time and the second time in a row, the United States Women’s National Soccer Team (USWNT) was in the spotlight. Discussions surrounding equal pay for women players gained momentum because of the unprecedented success of the women’s team, particularly in comparison to the US men’s team which did not even classify for the last World Cup.

Photo Credit: USWNT Players Association

Although the unfair compensation of women players became even more salient because of the outstanding success of the women’s team in the tournament, women players have been fighting for equal pay since before the World Cup. Back in March, members of the USWNT filed a gender discrimination lawsuit against the US Soccer Federation (USSF), accusing the federation of paying women less than men “for substantially equal work and by denying them at least equal playing, training, and travel conditions; equal promotion of their games; equal support and development for their games; and other terms and conditions of employment equal to the MNT.”

Of course, the issue is not that simple. Soccer players are also paid by their individual professional teams, which is where the majority of the disparities are created. Thus, while male players usually get paid much more by their professional teams and have salary security and benefits, women players earn less money overall. Women receive health insurance and maternity leave from the U.S. Federation, while men receive it from their individual teams. This deal, that altered the payment structure for women players, was negotiated by the union representing the USWNT two years ago. Despite this progress, attempts to settle the equal pay lawsuit through mediation have failed and, as a result, a trial is scheduled to take place in 2020. Nevertheless, other compensation and individual team payment complicates what “equal pay” actually means.

Lack of equal pay in sports is prevalent globally. The Norwegian player Ada Hegerberg, who was the best player in the world in 2018, earns more than 300 times less than Lionel Messi. Hegerberg refused to play for the Norwegian team in the 2019 World Cup in France in protest of the disparity between women and men’s soccer in the sport. The Brazilian striker, Marta Vieira de Silva, who scored the most goals in World Cup history among both men and women, also used the last World Cup to protest. Marta wore cleats with the symbol of the Go Equal campaign which was recently created to fight for equality across genders in sport.

Photo Credit: Johannes Simon – FIFA

Gender disparity in sports is a real issue. According to the Forbes rank, none of the world’s highest-paid athletes in 2018 were women. Serena Williams was featured in previous editions, but since she was on maternity leave, she was not included in last year’s rank. Yet, despite all the valid discussion, equal pay is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to issues involving gender in sports. Beyond salaries, women face many other institutional and cultural barriers in sports: less job security, lesser quality facilities, lack of access for girls, and fewer investments, among other issues.

The reality is that gender influences many aspects of athletics. Back in the 80s, political theorist Iris Marion Young (1980) was already arguing that “it is in the process of growing up as a girl that the modalities of feminine bodily comportment, motility, and spatiality make their appearance.” Consequently, the way women move, including the way they throw a ball, are influenced by the “tension between transcendence and immanence, between subjectivity and being a mere object” that women experience.

Gender stereotypes and gender norms prevent many young girls from getting involved in sports that are considered more masculine. Although the situation for women in sports has changed significantly in the last few decades, sports are generally still understood as part of a masculine world. The fact that we use men’s sports as the standard, referring to the male team as simply “the basketball team” while referring to the female team as “the women’s basketball team” is a good indicator of this issue.

Photo Credit: Erik McGregor/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

Language also matters when it comes to media sporting coverage. Firstly, there is a lack of coverage of women’s sporting achievements. Secondly, when women are featured, there is a focus on looks and attractiveness or their roles as mothers and other non-sports related attributes rather than their athletic ability. While men are typically associated with words like fast and strong, women are described as aged, pregnant, and married. Thus, the issues surrounding media coverage in sports are not only about women not being covered, but also about how they are covered. There is a hyper sexualization and objectification of women’s bodies in athletics.

Besides focusing on women’s physical appearances, the media plays a significant part in emphasizing the idea that some sports are masculine (such as football, ice hockey, basketball, etc.) while others are feminine (like gymnastics and figure skating). This dichotomy creates different expectations for male and female athletes and builds another barrier for women who wish to participate in “men’s sports” and vice versa. Women and men who go against these gendered expectations inevitably have their sexuality questioned and are subjected to homophobic comments.

Editor’s Picks:

Origin Capital: Financing Women to Improve Communities

Is Gender Equality a Numbers Game?

“Revenge Porn: The Understanding and Impact of Non-Consensual Intimate Images (NCII) Violence

In many ways, sports reinforce toxic masculinity. By establishing norms about what it means to be a man, sports produce and reproduce a culturally constructed conception of manliness that is understood as violent, unemotional, and sexually aggressive. One of the consequences of this toxic masculinity is high rates of sexual assault cases with male athletes as perpetrators.

On college campuses, all-male groups, particularly sports teams and fraternities, are more likely to commit sexual assault than other groups. Football and basketball players are reported as perpetrators at a much higher rate than men in the general college population. Crosset (2016) highlights some aspects that make sport teams in the university context a rape-prone environment: peer support for violence against women (locker room conversations), the normalizing of interpersonal violence, and institutional support of male privilege (for example, institutional practices that fail to hold athletes accountable for criminal behavior).

Another issue that seems far from resolved is that of transgender and intersex athletes. These athletes are often accused of having unfair advantages, with some people even arguing that they should compete in a completely separate category. However, this is a complicated issue, and most of these ideas come from ignorance. Here, the media plays another significant role in shaping the public’s perception of these athletes. By only reporting about trans and intersex athletes when they win, the media contributes to the creation of the perception of unfair advantage.

Photo Credit: Mike Gladu

For example, in the 2018 Masters Track Cycling World Championship, trans cyclist Rachel McKinnon won. After Jennifer Wagner, who placed third, commented that McKinnon’s was not a fair victory, McKinnon posted on twitter: “This is what the double-bind for trans women athletes looks like: when we win, it’s because we’re transgender and it’s unfair; when we lose, no one notices (and it’s because we’re just not that good anyway). Even when it’s the SAME racer. That’s what transphobia looks like.” In this statement, she highlights the fact that Wagner actually beat McKinnon many times in the past years, but no one talked about it.

There are many ways in which sports and gender are intertwined, making women’s experiences in sports more challenging. The construction and reproduction of gender dynamics in the context of sports have effects that go beyond the individuals involved. Gender dynamics feed into the systemic oppression of women in society. If we want to change the way women experience sports and transform athletics into a more equal and just space, we need to discuss more than just equal pay- we need to start thinking and talking about all the ways in which sports are gendered.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

Featured Image — USNWT players celebrate with the FIFA 2019 Women’s World Cup — Photo Credit: Maja Hitij/Getty Images

REFERENCES

Crosset, T. W. (2016). Athletes, sexual assault, and universities’ failure to address rape-prone subcultures on campus. In S. C. Wooten & R. W. Mitchell (Eds.), The crisis of campus sexual violence: Critical perspectives on prevention and response (pp. 74-91). New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Young, I. (1980). Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality. Human Studies, 3(2), 137-156.