As talks at the UN’s biodiversity conference, COP15, continue in Montreal, a new scientific study has been published which predicts that by the year 2100, 17.6% of species will be extinct.

Species extinction is not a new concern, with the IUCN red list finding that over 28% of examined flora and fauna species – more than 42,100 in total – are in danger of extinction. However, this latest study published in “Science Advances,” is groundbreaking in its use of modelling technology, mapping out the intricate food webs and impacts on local species under different climate change-related conditions.

The scientists who conducted the study modelled hundreds of earth simulations populated by over 33,000 species. From these simulations, they predict that between 6% and 10% of animal species will be lost by 2050, and between 13% and 27% will be extinct by 2100, depending on the outcome of different plausible climate change scenarios.

The article found that the biggest cause of species extinction was climate change, at around 62%, followed by secondary extinctions (20%), local extinction due to competition from invasive species (14%), and land-use change (4%). Quantifying secondary extinctions in this way – for example, when a predator goes extinct because its prey food source has disappeared – is a turning point in measuring the holistic impact of climate change on Earth’s fauna.

The study offers a fine-grain analysis of interacting species networks, as well as a number of simulated scenarios where many animals were shown to be capable of adapting to the weather conditions of the previous year. However, while an ability to adapt in this way meant animals possessed robustness to consistent weather conditions, the model showed they did not fare so well when responding to sudden changes.

While this model is very exciting for climate research; allowing us to have a clearer idea of the widespread impacts of different scenarios of carbon emissions, it does still have its limitations. The scientists explain that the model does not produce an “Earth replica,” but instead aims to build an “ecologically plausible Earth.” It is no crystal ball to show Earth’s future, but instead “projects relative potential scenarios based on different assumptions” (predominantly carbon emission levels), and “reveals the underlying processes leading to these outcomes.”

Related Articles: Over Two-Thirds of Wildlife Lost in Less Than a Lifetime | Humanity’s “War on Nature”: New Global Biodiversity Deal Urgently Needed | COP15: Giant Jenga Tower Goes on Display to Represent the ‘Dangerous Game We Play With Biodiversity’ | Ocean Acidification: Time Switfly Running out to Avoid the Worst Impacts, New Report Warns

Another limitation of the model is that it only measures vertebrate life. It works on the assumption that all plant life, insects, and invertebrates are inexhaustible food sources, not subject to the effects of climate change – a presumption which the scientists warn could lead to underestimation of the coextinction effect.

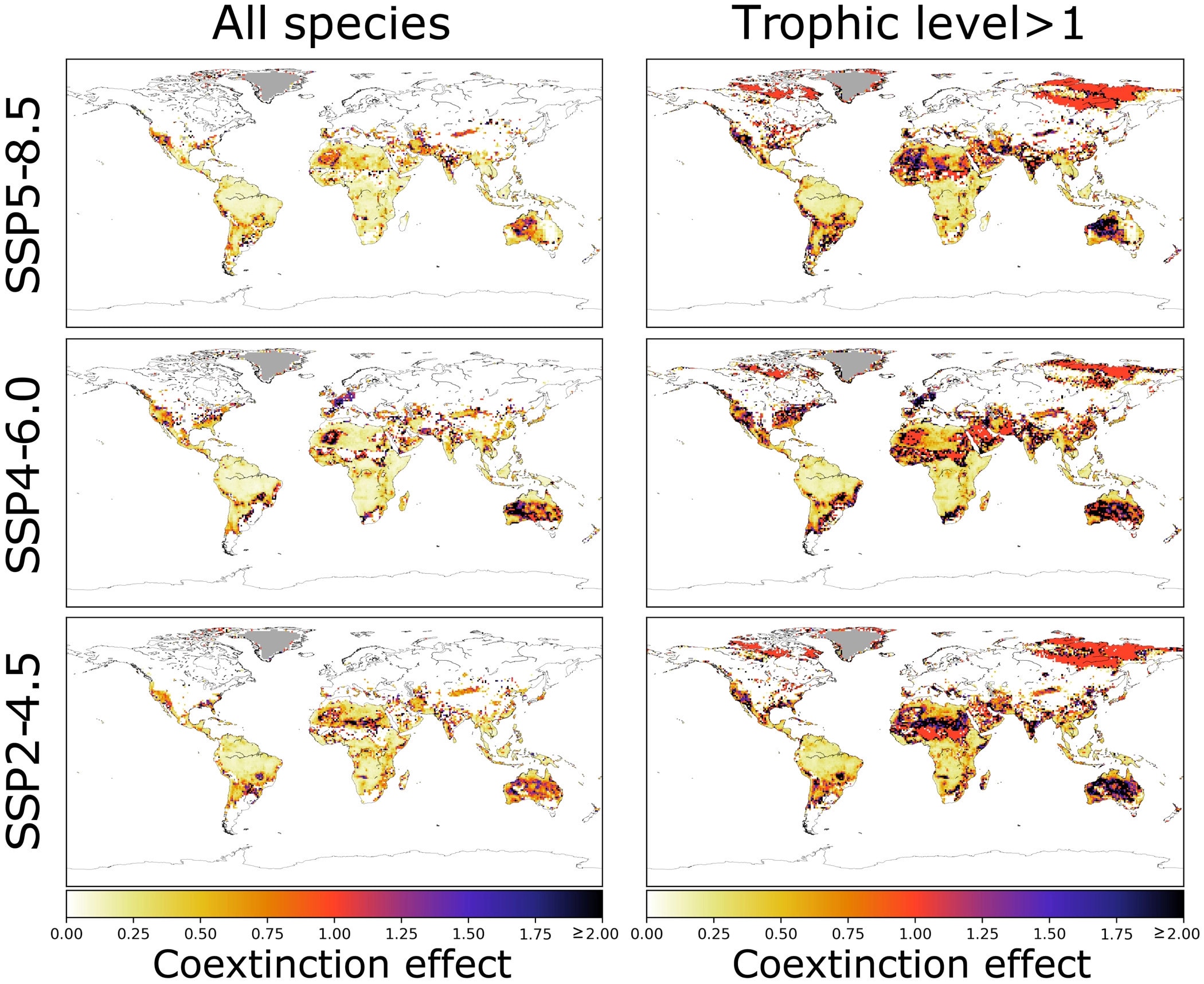

To address this potential bias, the group ran a supplementary simulation that only accounted for animals higher up the food chain (not including herbivores and insectivores), the results from which showed an even greater level of coextinction than the initial model.

The scientists claim that while the model does somewhat show loss of habitat as a factor in the loss of biodiversity, it does so to a lesser extent than will actually occur as a result of climate change. The model was also adjusted to account for so-called “random extinctions.”

From the above graphs it appears that, as is common with many of the effects of climate change, the Global South is disproportionately affected by the coextinction effect.

Worryingly, the article also found that “in all climate change scenarios… the average rate of diversity loss was higher from 2020 to 2050 than from 2051 to 2100.” In light of this, the scientists warn that “the bleakest time for natural communities might be imminent and that the next few decades will be decisive for the future of global biodiversity.” Again it is clear that to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, as well as mass species extinction, the time to act is now.

Discussions of the ocean have been oddly absent from COP15 negotiations, and it seems that the representations of this model – if not the model itself – have possibly fallen into a similar trap.

It is no secret that the oceans are vastly under-protected in comparison to land (just over 1% of oceans are protected compared to 15% of land), despite covering 71% of the Earth’s surface and representing 95% of the Earth’s biosphere. This may, in part, be due to the fact that the high seas (any area more than 200 nautical miles from a country’s coast) are subject to no national or international jurisdiction, although the UN is currently trying to find a high seas treaty which may well prove key in protecting marine biodiversity.

In fact, the study makes no special mention of oceans, seas, or marine life at all. Still, there is no reason to suppose that this hugely important element of global biodiversity has been disregarded, except that in all the maps generated showing the impacts of climate change and related issues, only land is represented. If the model does not include marine wildlife, then this needs to be stated more explicitly. If it does, then ocean biodiversity needs to be more clearly represented, as this is a key area that is being underrepresented in climate talks as delegates (understandably) consider foremost their own territories.

Overall, this new model is a very useful tool for mapping out the effects of climate change on global biodiversity across a range of specific scenarios and outcomes. However it does have its limitations; not considering flora or insect populations may lead to yet more unexpected climate consequences, and the study also needs to show clearer impacts on not just land animals, but also marine life.

The mass loss of biodiversity worldwide is not a new concern or phenomenon, but this model may further clarify some elements and the extent to which loss might occur. Ultimately, however, these findings providing a wake-up call is still doubtful, as studies with similar findings (though perhaps not to this extent) have been publicly available for years. One can only hope that a renewed sense of urgency goes forward in the COP15 discussions and future climate negotiations, both nationally and globally.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Emperor Penguin. Featured Photo Credit: Christopher Michel/Flickr