The summer of 2022, one of the hottest and driest on record, has been hailed as a warning of things to come. With unprecedented floods, droughts, storms and heatwaves becoming more common across the world, we hear less and less about the chronic tragedy of the two billion people around the world suffering a water shortage with no access to safe water.

A new report by the Global Commission on the Economics of Water has found that the supply of freshwater on Earth will fall short of the demand by 40% before 2030. According to the report, areas that are water-constrained will suffer the most with “severe shortages.”

Increased scarcity of water also means reduced biodiversity and a failure to minimise the impacts of climate change, the report highlights.

“A three-headed global water crisis”

As far as causes for water shortage, the report outlines three key reasons: water is misused and polluted, climate change means episodes of extreme rainfall — too little or too much — are becoming more frequent and more severe, and human action has now greatly affected the hydrological cycle.

Over-abstraction, or taking water from beneath the ground faster than it can be replenished by rainfall, is an example of water misuse. Groundwater from aquifers is the most common source of freshwater in Europe but over abstraction means the aquifers sink and salt water pours in, contaminating fresh sources.

Freshwater pollution is another reason for the severe water shortage. Pollution of freshwater most commonly occurs when rain washes human waste into rivers and lakes. Two billion tonnes of human waste, including municipal, industrial and agricultural waste like chemical fertilisers, enter our waterways everyday.

Global warming can also affect the amount of rainfall we get each year — this is because as the oceans warm up, there is an increase in evaporation. The water vapour rises and condenses into clouds — once over land, precipitation, or rainfall, occurs.

Naturally, the more oceanic evaporation due to climate change, the more rainfall we see. According to the report, there is a 7% increase in atmospheric water vapour for every 1°C increase in temperature.

Last summer for example, Death Valley — one of the naturally driest places in the world — saw 75% of its annual rainfall in just three hours.

So if we are seeing more rainfall due to climate change, why are we facing a water shortage?

Increasing temperatures are exacerbated by the natural annual temperature fluctuations. This means that in summer, more warm air is rising and then rapidly falling, creating high pressure in the atmosphere. The winds caused by the movement of this air make it harder for clouds to form. This means we are seeing more periods of extremely heavy and extremely light rainfall.

Human activity is also affecting the hydrological cycle, contributing to drought.

Changes in land use such as deforestation and infrastructure development, the report says, mean there is less vegetation where freshwater can be stored. This increases the likelihood of a hydrological drought — characterised by the effect low levels of rainfall will have on water stored on land, such as in reservoirs or aquifers.

Related articles: Water Could Limit Our Ability to Feed the World. These 9 Graphics Explain Why | How Environmental Racism Has Caused a Water Crisis in Mississippi | It’s 2023 and There’s Still a Global Water Crisis | The Value of Water-Smart Agriculture

What can be done to prevent a critical water shortage?

This report highlights that we still might have a long way to go to achieve SDG 6 — the availability of safe water for all — before the 2030 deadline. But with World Water Day just around the corner, the report does offer some insight on how to move towards water sustainability.

The report calls for a “seven-point call to collective action,” and details initiatives that include managing water as a “global common good” — meaning that we must recognise the links between communities and the way in which climate change and water reserves are intertwined.

A One Health approach would be ideal as it would sufficiently recognise the interconnections between the environment, people and their needs, and global biodiversity — all of which are threatened by water shortages.

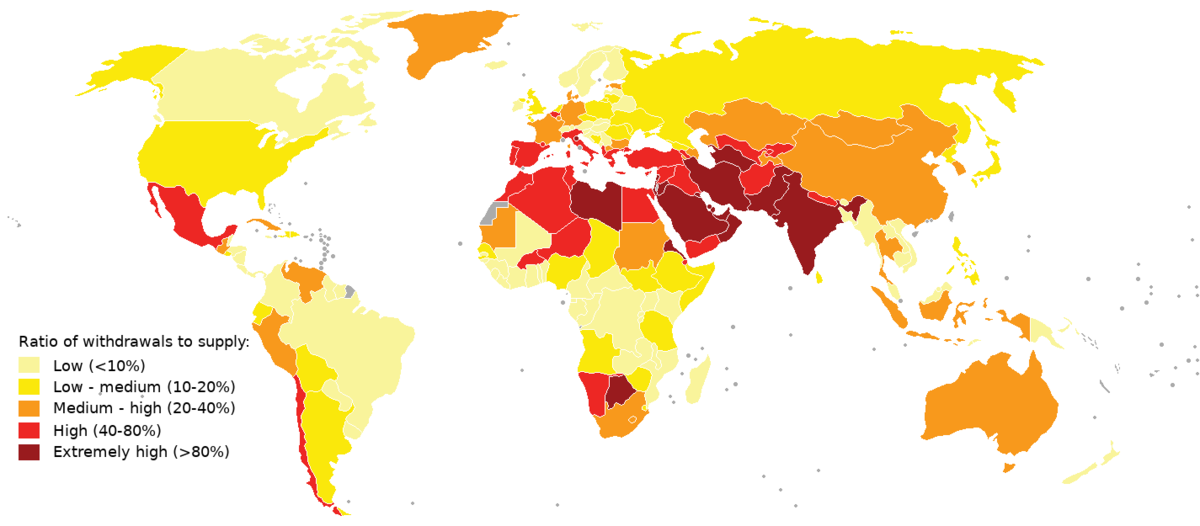

@FAO report shows the world is not on track to achieve #SDG6

Discover how countries are progressing towards the SDG targets linked to water-use efficiency & water stress

https://t.co/iwoEmC5ihe #WaterAction #UN2023WaterConference pic.twitter.com/SwMnDNSVqG

— FAO Statistics (@FAOstatistics) March 18, 2023

Mariana Mazzucuto, co-chair at the Global Commission on the Economics of Water and professor at the University College London says: “There’s no one country that’s going to solve this on their own, so we need an absolute, collective framework.”

This would include reshaping the multilateral governance of water that already exists, the report details, calling for the elimination of inconsistencies in the way water is managed through methods like the production of better data to allow for early warning of weather events, appointing a UN Water Envoy to lead and coordinate these efforts, and strengthening connections between the UN, the World Bank and other financial institutions to create better access to resources dealing with water.

There is a sense of optimism moving forwards, the report notes, as the water crisis provides the opportunity for technological innovation and reshaping the way the global community functions.

But one thing is clear, the situation is critical and global cooperation has never been more urgent or necessary.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Collecting water from Lake Kivu, Eastern DRC. Featured Photo Credit: Flickr courtesy of Oxfam International