Among the many notable developments in China’s overseas investment in recent years is the growing interest among Chinese companies in achieving certain internationally recognized environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. Whether motivated by growing international scrutiny, Chinese government guidelines on corporate social responsibility (CSR), or lessons learned from an expanding portfolio of international projects, CSR is now a topic of interest for many of China’s major overseas investors.

Like many of their international counterparts, Chinese companies are at various stages in their application of corporate social responsibility principles. However, there is considerable variation in performance and outcomes among the many Chinese companies operating abroad. While some are only beginning to consider the value of strong ESG commitments, others have already invested extensively in education, health advancements, and other programs in host countries. Some have even looked to international standards, such as ISO 26000, for guidance on assessing and addressing social issues.

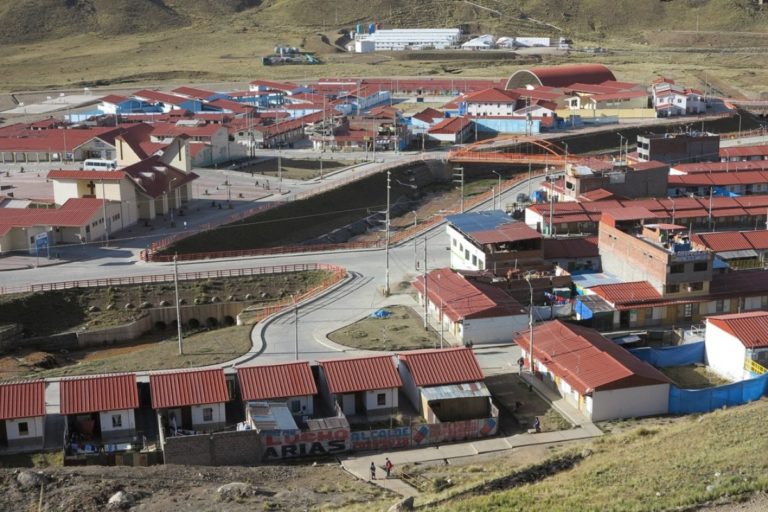

In Latin America, Chinese CSR-type activity is evident in a number of different countries, but is especially well documented among the Chinese firms in Peru. Examples include China National Petroleum Corporation’s (CNPC) investment in a 200-million-dollar wastewater treatment system in the Talara Oilfield, Chinese mining company MMG’s educational resources program in Las Bambas, and Chinese aluminum company Chinalco’s construction of an entirely new town for residents displaced by an open pit copper mining project.

Photo Credit: TNS

Chinese companies have also become increasingly active in their country’s responses to natural disasters in foreign countries. Disaster relief is still mostly handled by the Chinese government, often through the Red Cross Society of China, which falls under China’s State Council. But, a number of companies provided their own assistance to Ecuador and Mexico following earthquakes in 2016 and 2017, respectively, and to Peru after extensive flooding there in 2017.

In all three cases, Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei offered emergency telecommunications-related repairs. CAMC Engineering, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), and Yan Jian Group offered machinery for rescue and reconstruction in Ecuador and Peru. Gezhouba, a Chinese construction firm, and China International Water and Electric Corporation (CWE) contributed rescue and medical assistance responders in Ecuador.

Editor’s Picks:

The Open Amazon and its Enemies: A Call for Action and Optimism

Why is There Still a Debate Over Fracking in Mexico?

And Change is Coming Whether You Like it or Not

Continued Chinese progress on CSR will be increasingly critical in the coming years, not only for the well-being of communities where Chinese companies are present, but also for the reputations of Chinese companies, especially since they are spearheading China’s now-global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese president Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative. The negative externalities of projects-gone-wrong can have long-lasting implications and can affect prospects for future investment, as well as overall perceptions of the BRI.

Progress on CSR is especially important given the relative social and ecological impact of Chinese investment, which remains heavily concentrated in extractives and infrastructure development. According to the Financial Times, from 2014 to 2018, about a quarter of all Chinese mergers and acquisitions in Latin America and a third of all greenfield investments were in extractive industries, including metals and fossil fuel energy. In Latin America and other regions, Chinese companies continue to face backlash over their social and environmental impacts. Some examples include Sinohydro’s Coca-Codo Sinclair dam project and Chinese mining company MMG’s transport of copper through Apurímac region of Peru.

Photo Source: People’s Dispatch

Chinese companies must note, however, that even robust CSR practices aren’t guaranteed to reduce reputational and financial risk, especially if companies choose to invest in projects with outsized social and environmental impact. Several of the high-profile infrastructure projects that Latin American governments have asked for China to finance, such as the Rosita dam project in Bolivia and Ecuador’s Coca Codo Sinclair dam, had previously been rejected or tabled by multilateral development banks in light of environmental and social risks. Deals of this sort will incur social and environmental costs that no amount of public programming can adequately address.

Corporate social responsibility should also increasingly be understood by Chinese companies not just as philanthropy, but as a form of self-regulation to a wide range of stakeholders. Academic analysis suggests that Chinese companies generally comply with clearly articulated and enforced environmental (and other) regulations when operating overseas. However, communities in the US, Latin America, and other regions are increasingly looking to corporations for leadership on values like inclusion, empathy, and environmental preservation, especially in the face of questionable policy decisions by their own governments. In most cases, Chinese companies haven’t yet moved beyond defensive or brand-building philanthropy toward company-level CSR strategies that are supportive of wide-ranging development goals. This remains a challenge for many other multinational companies as well.

Chinese companies and ministries are making notable progress toward defining and applying corporate social responsibility, both at home and abroad. Progress is necessary, however, especially as companies look to grow their extractive sector investments and extend the BRI beyond the Eurasian region. Chinese companies can be leaders in CSR by working to advance development goals in the countries where they are operating, voluntarily integrating social and environmental concerns in their business processes and relationships, and more effectively linking CSR to company strategy. The architects of the BRI are also uniquely positioned to consider and account for the aggregate effects of Chinese overseas investment. The health and well-being of local communities, host countries, and the planet at large will require that they do so.