Now more than ever, the spotlight is shining on the entrenched relationship between health and food. The COVID-19 pandemic has moved dozens of health systems to the brink in low-, middle- and even in high-income countries, and threatens to undermine food systems around the world. If more corrective action is not taken, we are at risk of losing many gains made to improve health and well-being.

Even in the best of times, the systems that deliver our food and healthcare are seldom effective in working together to deliver sustained good health. Having worked for nine years in food and nutrition and another nine in health, I see several ways practitioners across health systems and food systems can greatly improve collaboration. Here I touch on the relationship between food and health and COVID-19, summarize lessons learned from the crisis, and propose three trans-sectoral solutions that can help sustain the delivery of quality healthcare and nutritious foods.

Food systems and COVID-19

Intuitively we get it: a nutritious diet is critical to good health.

However, is it widely known that a suboptimal diet is responsible for more deaths than any other risk globally, including tobacco? Earlier this month, a systematic analysis confirmed this following a review of the health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries.

Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. Approximately two billion adults are overweight, and of these over 650 million are obese. Forty-eight countries now face a crisis with a coexistence of high levels of undernutrition and overweight and obesity.

How is this relevant to COVID-19?

We’ve known for some time that there is a strong association between obesity and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). This holds true for COVID-19 as highlighted by a number of recent studies including this study led by Imperial College London. It showed that following age, obesity is the single biggest risk factor associated with serious illness related to the virus. This commentary in Nature notes that patients with type 2 diabetes may have up to 10 times greater risk of death when contracting COVID-19. Without even considering the costs associated with COVID-19, preventing obesity and diabetes makes economic sense. The per capita healthcare costs of treating obesity in the United States alone is shown to be over 80% higher for severely or morbidly obese adults than for adults with a healthy weight.

COVID-19 is poised to significantly increase the number of malnourished individuals globally. COVID-19 has laid bare the dearth of available and affordable nutritious foods in many countries, a lack of sufficient food system capacity to respond to the crisis; and the inability in many countries to collect and analyze up-to-date data on who needs immediate support.

To cite a few examples, food availability has become an issue in the US, a country known for its abundance; in Germany, food banks have temporarily stopped operating depriving many of essential food supplies; and some 300 million primary school children – many in LMIC — no longer have access to their regular (sometimes only) nutritious meal at school due to school closures.

Health Systems and COVID-19

The significant strain COVID-19 is placing on health systems is widely known. Many countries’ health systems – including seven LMIC with which my company works – are scrambling to respond using already limited resources. This is creating risk that other essential health services do not get the attention they need now and in the future. For example, there has already been a deferral of measles immunization campaigns in 25 countries including countries experiencing a measles outbreak.

“Let food be thy medicine.” Hippocrates

The current situation points to a key opportunity, to an imperative.

Considering the lessons learned, solutions are urgently needed which are trans-sectoral, that incentivize healthy eating, and which make certain that resources are available within systems to deliver quality healthcare and nutritious food even during crises. Such solutions include food ‘sin’ taxes and subsidies, value-based health insurance programs, and dynamic fiscal management for health and food systems.

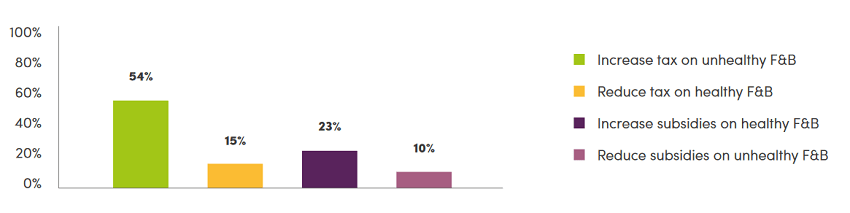

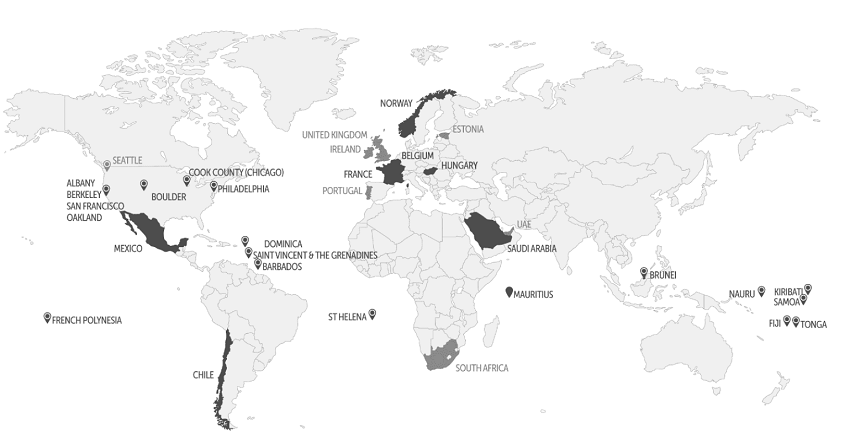

1) Food ‘sin’ taxes and subsidies: A 2016 systematic review showed that these two fiscal instruments can result in a decrease in the purchase of products high in salt, fat or sugar; and an increase in the purchase of healthier foods, respectively. Since 2011, when the UN recommended ‘fiscal measures’ as an approach to improve diets, momentum has been growing to use these instruments in national health plans. Some countries earmark revenue generated from sin taxes for health systems. One model estimates that nutritious food subsidies in the US alone could save US$39 billion in healthcare costs by preventing hundreds of thousands of cases of heart disease and diabetes.

Despite the evidence of impact, food taxes and subsidies are vastly underutilized. Only 39 countries report using fiscal policies to improve dietary intake (Figure 1), and only 30 jurisdictions have sugar-sweetened beverage taxes (Figure 2).

2) Value-based health insurance: Health insurance typically covers essential medical procedures, prescriptions and provider visits. However, value-based, food-sensitive insurance programs are rare. Where deployed, they incentivize healthy eating, and stem rising healthcare costs by improving individual and community health.

Both in Germany and in Switzerland, public and private health insurance programs offer bonuses or discounts, respectively, for those who follow a healthy diet. In Pennsylvania, USA, Geisinger’s Fresh Food Farmacy (FFF), offers 22,000 pre-diabetic and diabetic residents diabetes education and healthy, subsidized food rather than diabetes drugs. The clinical results are compelling. While medications typically offer a 0.5-1.0 point reduction in HBA1C levels, patients in the FFF program have average reductions of 2.0 points after six months. The economics are also persuasive. It costs just US$3K a year to manage one patient enrolled in FFF compared to US$48K a year for traditional programs.

Value-based, food-sensitive health insurance programs represent a step in the right direction for health systems. As their evidence of impact increases, they should be rolled out to improve prevention and treatment, and link food systems and health systems.

3) Dynamic fiscal management for health and food crises: In response to COVID-19, WHO reports that dozens of countries have now enacted new budget laws that give leaders authority to quickly reallocate budgets or to release supplementary funds. The shared feature in each case has been the declaration of a state of emergency creating the space for increased and faster spending. However, there has been an absence of a concurrent deliberation looking at the fiscal space for food systems and food delivery. Budget measures during emergencies must consider both accelerated health system spending as well as food system expenditure, and this dynamic fiscal management should be institutionalized so that countries can expand both healthcare and strengthen food supply chains in times of crisis.

COVID-19 and Beyond

While the current pandemic may be exploiting weaknesses in our health and food systems it has also helped shine a light on the opportunity to bridge divides. The three solutions summarized here – food sin taxes and subsidies, value-based health insurance and dynamic fiscal management – are inherently trans-sectoral, requiring engagement with practitioners and experts across health systems and food systems. They can help incentivize better diets and improve the delivery of quality healthcare and nutritious food sustainably in normal times and in times of crisis.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com