In Central America, looking at the future allows prioritizing the most robust investments for climate adaptation.

Article in collaboration with: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) seeks to address the increasing challenge of global warming and declining food security on agricultural practices, policies and measures through strategic, broad-based global partnerships.

The investments Central American countries will make in infrastructure, public policy programs and capacity building are crucial to adapt to climate change, particularly for the countries that share the already drought-prone Dry Corridor.

Related topics: Imagining challenging climate futures – Investment in Climate-smart Agriculture: Why Do it Now – Gender, climate change and agriculture: Guatemala leads regional dialogue

These investment decisions will be taken in the coming years, but they will shape the coming decades. For example, an arid zone irrigation system or a vegetable wholesale center for smallholder farmers must serve an entire generation. Given the region’s scarce monetary resources, it is essential that these decisions are future-proof and consider all variables that may affect them, including climate change and other social, environmental and economic processes. A Common Journey, a project that is part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) portfolio and led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), seeks to strengthen this type of decision making with the creation of scenarios: multiple stories of the future told through words, numbers or images.

As we wrote in a previous blog, future scenarios are created in workshops through an approach that “throws off the current straitjacket.” They explore how a region or country could develop in the future by integrating climate change with other drivers of change, such as levels of socio-economic development and different government regimes. These different scenarios then enable policy makers to explore diverse future pathways. However, it is not just a theoretical exercise. This methodology is most useful when the scenarios actually inform decisions and policies that will affect the most vulnerable people in the region.

CCAFS Scenarios Central and South America Coordinator and @_RE_IMAGINE_ colleague @MariekeVeeger on how @CGIARclimate scenarios work helps countries anticipate climate change. https://t.co/RraqOh9TRA pic.twitter.com/OKeriuryil

— Re-imagining anticipatory climate governance (@_RE_IMAGINE_) May 30, 2019

However, through the use of future scenarios they create a deeper understanding of a country’s long-term dynamics. These collaboratively created future scenarios that go far beyond the five- to six-year time horizon allow IFAD to systemically anticipate and address long-term challenges. Juan Diego Ruiz, head of the IFAD subregional office for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, explains: “This methodology, these scenarios, are important inputs for the upcoming national strategies of Guatemala and El Salvador. They fit with our participatory approach.”

In short, future scenarios imagine how socio-economic processes will evolve in the coming decades, and how they will interact with climate change and the investments IFAD intends to make in the near future. This way, the future is better understood and anticipated, and the decisions made are more robust.

“Our research shows that most plans and policies in Central America take into account that climate can vary, but only few consider that other aspects of society can also change. This makes plans less resilient to changes in the environment and decision-making more reactive than proactive,” says Marieke Veeger, Scenarios and Policy Researcher for CCAFS, Utrecht University and the University for International Cooperation (UCI). Veeger is collaborating with the global RE-IMAGINE research project, which is aimed at understanding how the anticipation of futures can improve climate governance in regions most vulnerable to climate change.

Local decisions

This same approach could be applied across different scales of Central American state systems, but you have to start at the top. Ideally, by presenting these methodologies to leaders and ministers—those who make the big planning decisions, explains Miguel Gallardo, climate change specialist at the El Salvador Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN). While the future scenarios method does not provide all the answers, it will help improve decision-making. “It puts the compass in the right direction. Without it it’s difficult to know where to start,” says Gallardo.

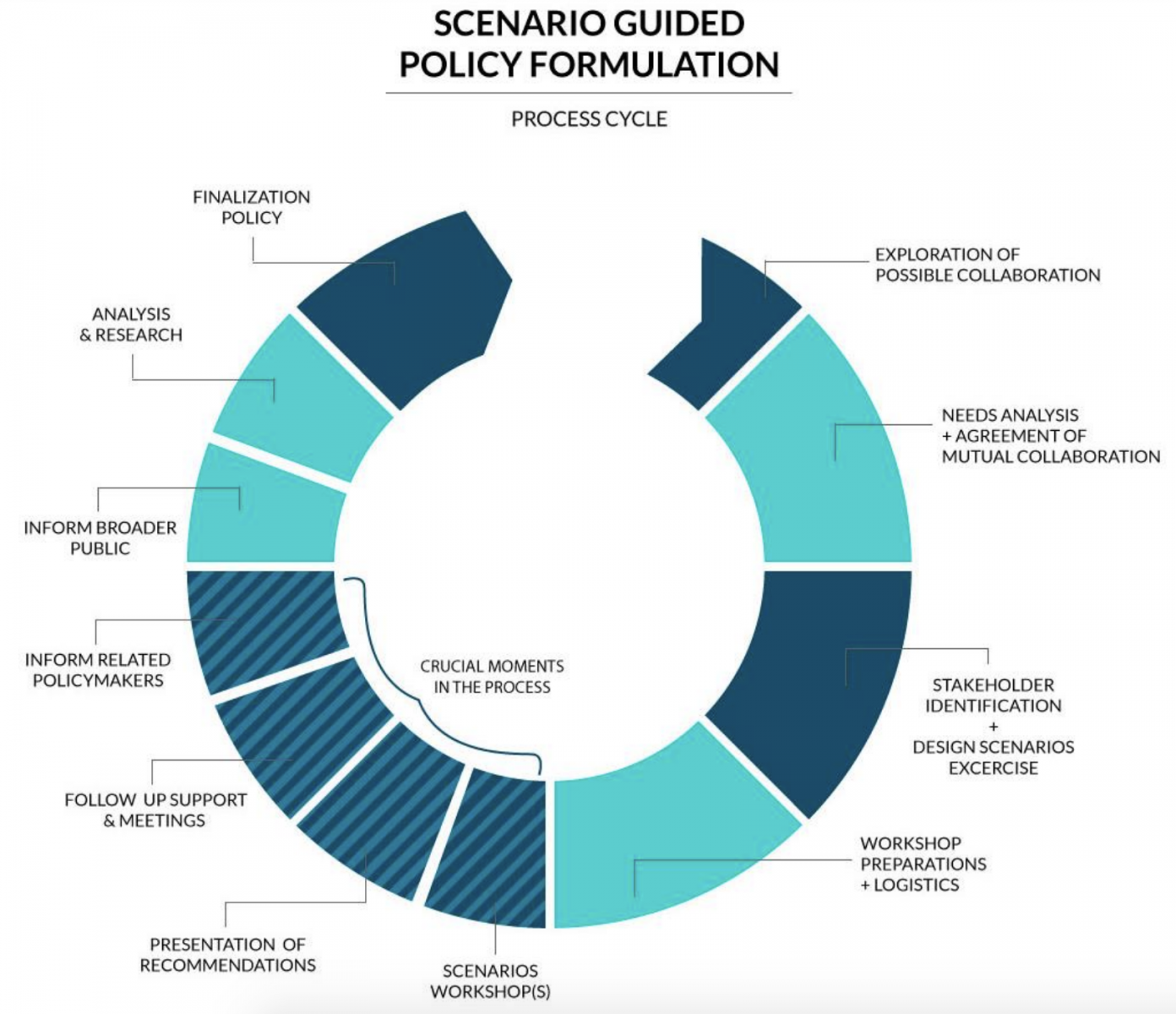

Process cycle for scenario guided policy formulation. Source: Veeger et al. 2019

However, reaching high-level decision-makers is a major challenge, explains Ruiz (IFAD). He points out that the main challenge is that most decision-making is situated in a political and media context focused on putting out metaphorical fires, with resources going to immediate needs. “Their long term is this afternoon,” he says about the overwhelmed decision-makers in the region. These urgent pressures overshadow what is important in a region that needs long-term planning to shape its sustainable development goals and its commitments to reduce emissions.

One way to keep these long-term scenarios linked to the ever-changing present is to keep track of the change factors (the factors identified by stakeholders as important drivers or impediments to change) from which future scenarios arise, suggests Raúl Cárcamo, coordinator of the Early Action Project for the Protection of Livelihoods, from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) El Salvador. “If the variables are monitored and tracked over time, you can see where the variables proposed in the scenarios tend towards,” says Cárcamo, who hopes this will help identify the emergence and evolution of these futures.

For example, in a scenario where the import and consumption of processed foods have increased, a government could encourage the consumption of fresh national products and monitor people’s eating patterns, the sale of certain domestic crops and the sale of junk food, all in advance. This could ensure more evidence-based decision-making.

This is why future scenarios are relevant for decision makers in 2019 or 2020. “When you start to generate information for the scenarios, you are also indirectly considering the present,” emphasizes Cárcamo.

A Common Journey is financed by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). This project aims to develop capacities for climate-smart agriculture (CSA) in Central America in order to strengthen policies and decision-making for climate change adaptation and mitigation actions.

About the author: Diego Arguedas Ortiz is founder and editor of Ojo al Clima.

The blog has been edited by Charlotte Ballard, Communications Officer for the RE-IMAGINE project; Lauren Sarruf, Communications Officer for CCAFS Latin America; Lili Szilagyi, Communications Consultant for the CCAFS Flagship on Priorities and Policies for CSA; Leanne Zeppenfeld, Communications Student Assistant for the CCAFS Program Management Unit; Marieke Veeger, Scenarios Coordinator, CCAFS/UCI.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Photo Credit: Alfonso Ralda