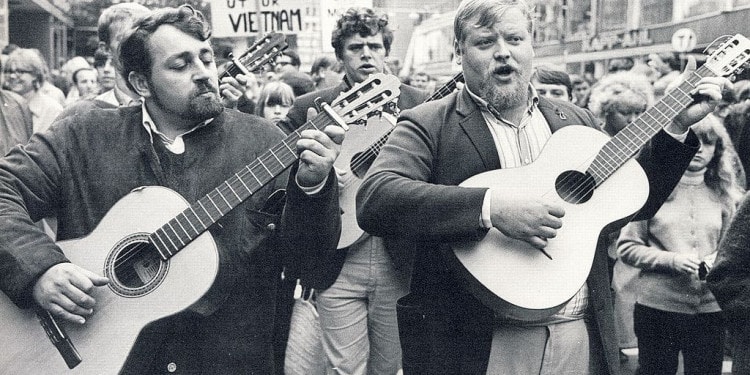

Protest songs are nothing new. Music has always functioned as a way to express that which could not be said. The function and format of politically-charged music might be constantly changing but its power to connect and communicate has always existed.

Music’s political function has varied hugely over its long span; sometimes protesting, sometimes lamenting. The fusion of poetry and music in song has a certain universality which seems to suit it to expressing deep, raw human emotions and struggles, and to speak universally to us as a species, transcending boundaries like class, sex, age or nationality. The enduring popularity of the kind of low-tech music far from the big record companies or marketing gurus – such as gospel or, in their early days, artists like Bob Dylan – equipped only with guitar, harmonica and a raspy voice – is testament to this power.

Even in the eighteenth century music was causing controversy. Mozart was castigated for casting the aristocracy in a bad light and implying the equality of servants to their masters in his Marriage of Figaro – a musical adaptation of one of a trilogy of caustic plays with social commentaries written by Beaumarchais, the last of which, Tartuffe, was so controversial it was only adapted to opera in 1966. In Soviet Russia Shostakovich was, like many other composers, persecuted for music which was seen as rebellious for its style alone.

The restrictive aesthetic of Soviet Russia, dubbed Socialist Realism, demanded music which was folk-influenced, unchallenging, glorifying the idealised Communist Russia. Under this regime, Shostakovich’s intellectual, complex and avant-garde works were viciously denounced, his income from commissions dried up, and he was frequently in fear for his life as a troublemaker. After surviving the devastating Siege of Leningrad, his Seventh Symphony, known as the ‘Leningrad’ symphony, was a bitter lament of the incredible human suffering the city had witnessed. For once, its universal theme and its appeal to national pride even managed to please the authorities.

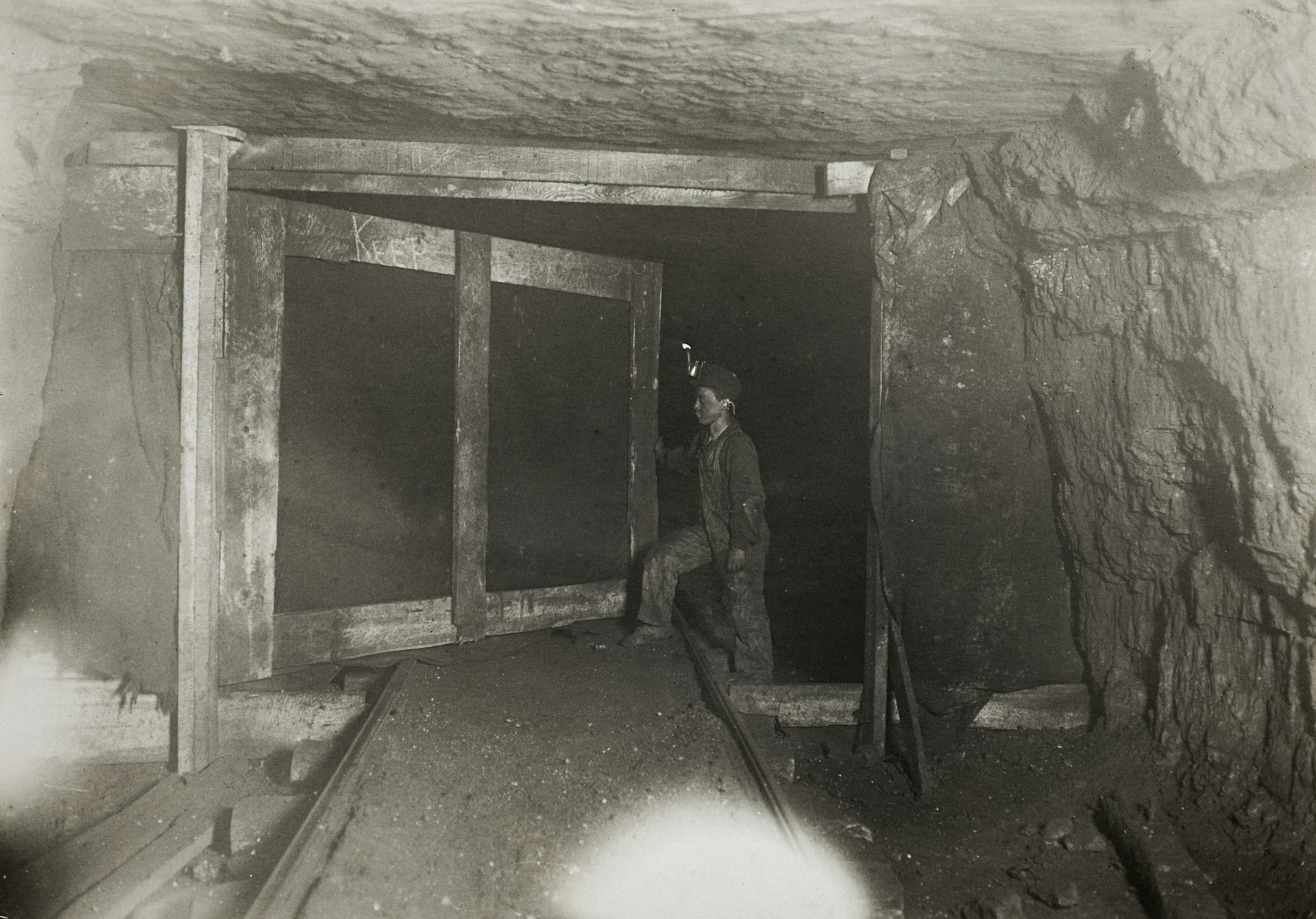

Church music, from medieval to the modern day, is also rich in themes of lamentation and protest, frequently also co-opted for other movements such as Civil Rights. Gospel music, emerging from black churches in America’s South and its history of displacement, slavery and deprivation, has a particularly poignant link to these universal and truly biblical themes. Countless parallels can be drawn between Biblical stories of oppression, deprivation, the fight for freedom, and the history of the southern States, and in both music and faith are ways of finding release or relief.

The boundary between gospel, blues and jazz is blurry not only musically but in content as well. Fellow products of black American culture, jazz and blues also frequently carry strong political and social messages. They emerged from the tumultuous and racially-charged context of the USA as the country went through the abolition of slavery and the continuing turmoils of the twentieth century – persistent and pervasive racism, lynchings, the social segregation of Jim Crow laws; the Civil Rights movement.

In the Sixties the Civil Rights Movement made ample use of the power of music – and the deep love people had for its stars, such as Nina Simone and Paul Robeson. In the Seventies, John Lennon and George Harrison were prominent musical activists, for peace and the relief of devastating floods in Bangladesh respectively. In the Eighties, Bob Geldof recruited music’s star power to combat the famine in Ethiopia.

Continuing this tradition, today protest music is becoming more prominent once again, more varied and less segregated than ever. It takes myriad forms: classical, traditional, folk and pop, they come together to highlight and protest the numerous injustices of our age.

In the USA in particular, protest music is undergoing a resurgence. The strong political and activist pedigree of hip hop has re-emerged in the wake of dramatic events in recent years, coming to a head almost exactly a year ago in August 2014. Public outcry escalated as news of police brutality and unprovoked shootings of black men, largely unarmed and innocent, continued to accumulate. The events in Ferguson, Missouri after the shooting of Mike Brown on August 9 were particularly high-profile. Riots and protests repeatedly shook the city from August until Christmas, and a police force equipped like a small army held the city in lockdown and imposed curfews.

Musicians across the USA, however, proved extremely diligent activists: the rapper Tef Poe was involved with the events in Ferguson and has been an especially insistent voice for change ever since; the day after Mike Brown’s death J. Cole released the pared-back, hard-hitting ‘Be Free’, while D’Angelo was incited by footage of the Ferguson protests to complete and rush-release his album Black Messiah – ten years in the making.

The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag arose on social media, and musicians joined in.

Artists including Lauryn Hill, Kendrick Lamar, Run the Jewels, J. Cole, D’Angelo and myriad more have nailed their manifestos to the door and taken a stand in the name of calling for an end to institutional racism and police brutality in the USA. In their acceptance speech for their Golden Globe-winning song “Glory”, composers Common and John Legend called the world’s attention to Ferguson, in many ways the same issues dealt with in the movie Selma, for which the song was composed. Lauryn Hill’s Black Rage is a furious diatribe against everyday injustices and discrimination which still plague minorities.

It remains to be seen how governmental responses to this spotlight on police brutality will pan out; but the efforts of activist musicians to highlight these issues, and the unifying power of music, have been fundamental in rallying hearts and minds to the cause.