Venezuela’s political, economic, and social issues have caused one of the biggest crises in the history of Latin America. Years of corruption, economic mismanagement, and consolidation of power have resulted in the decline of one of the wealthiest countries in the region. Recently, one of the most severe issues affecting Venezuela is the country’s situation with political prisoners and its resulting violation of human rights. This issue is so dire that it has been mentioned by multiple international authorities such as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. In the last 20 years, the regime in Venezuela has persecuted, detained, imprisoned, and silenced many of its citizens for thinking differently from the government or for expressing their rights.

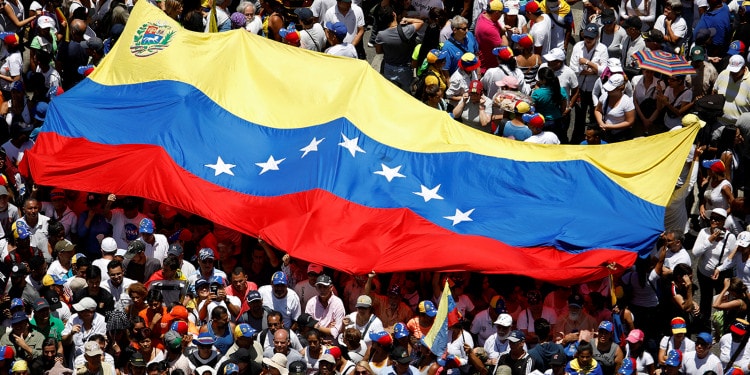

In 2019, the crisis reached a new level as a power vacuum was created by questionable 2018 electoral results. In the first quarter of 2019, the country experienced massive protests in which Venezuelans demanded the restoration of democracy, the rule of law, better economic conditions, and free and fair elections. Authorities reacted with a wave of brutal repression, causing casualties and increasing the number of people arbitrarily detained to historical levels. The number of political prisoners increased from 273 on January 21, 2019, to 983 on January 31, 2019.

This level of repression is not new in Venezuela. Since 2002, the Venezuelan regime embarked on the persecution, oppression, and detention of those who they considered a threat. The government has also corrupted institutions which were created to safeguard democracy such as the judicial system, which now interprets the law for the government’s political gain and creates conditions in which rule of law is only laying the groundwork for further arbitrary detentions.

During the first years of the Chavez government, the number of people detained for political reasons was significantly less than what it is today. Economic and social conditions were more stable and Venezuela did not receive as much international scrutiny as it sees today. Two of the most relevant cases during this period were the arrests of Ivan Simonovis and Judge María Lourdes Afiuni. Both arrests were made for purely political reasons.

The case of Ivan Simonovis comes as a result of the 2002 coup attempt in which he was accused of having shot at pro-government sympathizers during April protests. After a trial full of misconduct, Ivan Simonovis was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Photo Source: venezuelanalysis.com

The case of María Lourdes Afiuni demonstrates the dismantling of the rule of law in Venezuela. On December 31, 2009, Judge Afiuni ordered the conditional release of Eligio Cedeño following a report from the United Nations which categorized his detention as arbitrary. As a consequence of her verdict and after a televised address by President Chavez, Afiuni was arrested and sentenced for misconduct in the release of Cedeño.

Since 2014, the number of arbitrary detentions and political prisoners has grown in Venezuela. The political, social, and economic crisis launched Venezuelans to protest. These protests have resulted in one of the first waves of mass repression in the country and, consequently, has induced the incarceration of more political prisoners.

Foro Penal, an NGO that works against arbitrary detentions and in defense of human rights reports that from January 1, 2014, to July 31, 2019 there have been more than 15,151 people arbitrarily detained. In these arbitrary arrests, 848 civilians have been prosecuted under military courts. As of September 9, 2019, there are 478 political prisoners in Venezuela. While this number has declined significantly from the first quarter of this year, the level of repression and number of arbitrary detentions are a cause for concern.

It is challenging to define a political prisoner. We usually relate it to a person with a high public profile who is involved in a political or social movement that diverts from the regime in power. As a result of their deviance, activists involved in these organizations are persecuted, detained, and convicted on illegitimate charges. In Venezuela, this definition is partially correct. There are cases such as that of Juan Requesens, a congressman who remains arbitrarily detained on false charges since 2018. However, many political prisoners are simply civilians who were not involved in any political or social processes affecting the country.

Editor’s Picks

Post-Conflict: The Mass, Systematic Killings of Social Leaders in Colombia

Destigmatizing Migration: A Different Perspective

Maya of the Past, Indians of the Present: Racism and History in Guatemala

In recent years, the Venezuelan government has detained civilians who are currently or have been associated with persons they deem as threats or they have accused of conspiring against the status quo. Usually, these persons are not involved in any accusations laid against them. But, the regime uses this tactic as a way of intimidating anyone who wants to dissent against them.

One instance of innocent civilians who are political prisoners but were not involved in any political process is the case of José Alberto Marulanda. Dr. Marulanda is a surgeon who was arbitrarily detained on May 19, 2018. He was accused of participating in a conspiracy against the government because he was romantically involved with an army sergeant that the authorities accused of “conspiring against the government.” In the early days of his detention, Marulanda was subjected to torture by the DGCIM (Venezuelan military intelligence) which resulted in the loss of nerve function in his hands and a loss of hearing in his right ear.

Credit: Amnesty International Venezuela

He is currently detained at the Ramo Verde Military prison and has not received any medical treatment after being subjected to this torture. While being held, the judge has postponed the hearing where the evidence of his acts is to be presented because the authorities in Ramo Verde Prison didn’t take Marulanda to court. His preliminary hearing happened in December and the case remains ongoing.

Another innocent civilian being detained for alleged involvement is Ariana Granadillo Roca. Granadillo is a medical student that was initially held with her family on February 2, 2018 because she was living at the home of Colonel Garcia Palomo, a military officer who is a distant relative that was being investigated by the Venezuelan government for conspiracy. While she was detained, the authorities blocked her vision, beat her, and sexually assaulted her to get her to reveal the location of Garcia Palomo. She was released two days later with no explanation.

Three months later, on May 24, Granadillo was again detained by the DGECIM with her parents in their home in Miranda State. The authorities did not have a judicial order for their detention and did not disclose her and her parent’s whereabouts for a week to the Foro Penal lawyers. Granadillo was once again subjected to acts of torture as the agents tried to get her to reveal the location of Garcia Palomo, something she did not know. She was released on May 31 with no charges.

On June 23, 2018, Granadillo was taken from a bus by the authorities because there was an arrest warrant out for her from the DGCIM dated May 27, 2018. DGCIM agents took Granadillo and transferred her to prison and then to the military intelligence headquarters in Caracas. Foro Penal lawyers were present to defend her case. On July 3 she was taken to the military court and charged with instigating a rebellion because she had regular phone contact with Garcia Palomo’s wife and had received money from her while she stayed at the family’s home. Ariana Granadillo told her lawyers that she had phone conversations and received money for the expenses and care of the owner’s dogs. She was released under restrictive measures including prohibition to leave the country and requirement to check in with the court every eight days.

Like Ariana Granadillo, there are many former political prisoners who have been released, but they are not exactly free. Foro Penal reports that, as of September 9, 2019, 8,906 Venezuelans are subject to restrictive measures to their freedom for political reasons. These measures include prohibition from leaving the country or the city where they are located, prohibition from speaking to media outlets, restrictions of social media use, and a requirement to check in with an assigned court every specified number of days. While the number of political prisoners continues to decline, the number of people with restrictive freedom increases. This staggering number of people is a growing concern and a clear violation of the fundamental rights of Venezuelan citizens.

While domestic and international pressure has managed to reduce the number of political prisoners in Venezuela, the regime continues to detain people for political purposes. Foro Penal defines this action as the “Revolving Door Effect.” An example of this effect occurred one week after Michelle Bachelet, the UN Commissioner for Human Rights, visited. As the government prepared for the visit from Bachelet, it began to release several political prisoners in order to convey their compliance with UN standards. But, a week after the visit, authorities detained Antonia Turbay, a lawyer accused of taking photos of the authorities as they lived in the house of the recently escaped Ivan Simonovis.

As the crisis in Venezuela continues to escalate and international organizations begin to call for action, it is essential to highlight the number of abuses committed by the regime against the Venezuelan people. On Monday, UN High Commissioner Bachelet updated her report on the human rights issues in Venezuela. She called on the authorities to comply with the appeals given in the report such as the release of political prisoners. As Venezuelan authorities continue to ignore these calls for action, it is essential to inform and support the organizations that report these abuses. They continue to fight for the freedom of those who are and have been arbitrarily detained and to restore democracy and rule of law in Venezuela.