On Sunday, Stephen Spielberg caused a stir, when he announced that he “really and truly regret[s]” the impact that his 1975 movie, “Jaws,” has on sharks. In fact, he fears that “sharks are somehow mad at [him].”

With shark populations declining by 71% in the last 50 years, it is no wonder that the director worries about the marine animals’ lives, but where does “Jaws” actually fall in influencing the extirpation of these animals?

The movie depicts a sea-side community in New England being terrorised by a killer shark, and the efforts of the local chief of police, an ichthyologist, and sea captain, to track down and kill the shark. The harrowing tale was accompanied by an iconic two note score, and pinned sharks in public consciousness as “mindless eating machine[s]” that will “attack and devour anything,” as the film’s trailer describes them. “It is as if God created the devil, and gave it… jaws.”

Spielberg drew considerable inspiration from the works of Alfred Hitchcock, and has been praised for creating fear with something that, for the most part, the audience doesn’t see – the mechanical shark that was built for the purpose malfunctioning nearly constantly in the movie. However, “Jaws” is consistently pinpointed as a turning point in the Western treatment of sharks.

To what extent is this true?

In 2014, Christian Neff coined the term, “The Jaws Effect” – the trifecta of beliefs that sharks intentionally bite humans, that shark bites are always fatal, and that sharks should be killed in order to prevent future attacks. In 2016, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences released a study on recreational shark fishing that claims that “recreational shark fishing gained another significant boost in popularity in 1975 after the release of the blockbuster movie Jaws.”

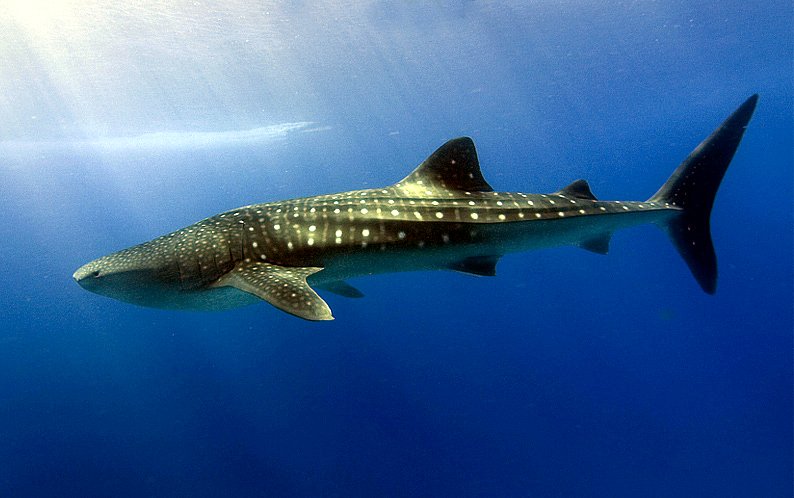

“Jaws” has had a long legacy in the depiction of sharks. First in fiction: one study analysed 109 shark movies made between 1958 and 2019, and found that 96% of movies overtly portrayed sharks as threatening to humans. The one film that portrayed sharks as non-threatening to humans was “Finding Dory,” with its depiction of a whaleshark. Examining film posters, many depicted shark species that do not exist.

However, this representation is not limited to clearly fictional sources. The US television show, “Shark Week,” is infamous for making up “facts” and fearmongering, despite advertising itself as an educational show. Running since 1988 and broadcasting in 72 countries globally, the programme remains immensely popular.

But is this depiction merely due to “Jaws?”

“Jaws” was a novel before it was a film, published in 1974 by Peter Benchley, who spent the rest of his life promoting the conservation of these animals.

Sharks were mostly disregarded until the Cold War, when the US military attempted to develop a chemical shark repellent, out of fear that sharks would interfere with their underwater missions. In the 1960s, a wariness and fear of sharks made its way into civilian consciousness. One could view Peter Benchley’s novel, which Spielberg subsequently made into a film, as a product of its time, rather than the herald of a new-found era of fear around sharks.

However, the fear around sharks would probably not have become as long lasting as it did if it weren’t for the best-selling novel and its film adaptation, which still holds its place in the pop culture hall of fame.

The IUCN red list holds overfishing as the “universal threat” to sharks and rays, being the sole threat for 67.3% of threatened species, and for the remaining third of species, interacting with factors such as loss and degradation of habitat, climate change, and pollution. Commercial fishing for sharks is very old globally, with records from the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279) describing the use of shark-fin soup as a traditional banquet staple. However, this is not as old in the US, with commercial shark fisheries becoming established between 1935 and 1950. Sharks are targeted for their meat, fins, gill plates, and liver oil, but are also frequently caught incidentally when fishermen are fishing for other quarry.

A newer threat to sharks is recreational and trophy fishing. Trophy fishing can be seen gaining popularity around the world as early as the 1010s, when it gained such popularity in New Zealand that grey nurse sharks off the coast of New South Wales were nearly extirpated from the water. It has also been seen in Australia, South Africa, and Ireland throughout the 20th century, but gained popularity in North America in the 1960s.

Related Articles: Over Two-Thirds of Wildlife Lost in Less Than a Lifetime | ‘Ocean Emergency’ Declared at UN Ocean Conference | Ecuador takes new steps to protect wildlife, creating a ‘sea highway’

However, “Jaws” did result in a boost in shark hunting, which lasted throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. The 1980s saw a huge increase in shark fishing tournaments within the US, particularly in the southeastern states. Between 1979 and 1986, the estimated number of sharks captured from Florida recreational fishing increased from 450,000 to 733,000 – a 63% increase in just seven years. The longest running shark fishing tournament was first held in 1987 in Martha’s Vineyard, where “Jaws” was filmed. It was known as the Monster Shark Fishing Tournament, ran for 27 years, and saw more than 25,000 sharks landed before changing name and venue in 2014.

With recreational shark fishing peaking in the 1990s in the USA, the numbers began to decline in the early 2000s, when conservation efforts and attitudes began to change. A number of shark-catching competitions changed their policies to catch and release sharks, rather than catch and kill them. Although catch and release methods of fishing are supposed to have low-to-zero mortality rates, in actual fact, fatalities can be higher 90% for some species, depending on gear used, fishing practice, and the environment where this occurs.

Since the early 2000s, there has been a more popular conservationist attitude towards sharks, recognising that the majority of shark species are non-aggressive towards humans. However, when more informative articles are published about sharks, they are often written under the mode of subverting expectations, luring readers in with sensationalist headlines about the perceived dangers and awesome threats posed by sharks.

While this can be a useful and informative tool, regardless of the content, the sheer number of headlines that fall under this category contribute to a media haze of fear.

Historically, sharks have been seen as a nuisance to fishermen. Amusingly, they might be coming to fill this role again. Fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico have been complaining about the expensive damage that tiger, bull, and sandsharks, among others, have done to their equipment, be it by biting through lines or bending hooks.

However, sharks are necessary to maintaining the delicate ecosystems of the ocean, and keeping fish supplies plentiful. If you remove the apex predators from a food chain, then their prey becomes too plentiful, over-consuming the next trophic level. Sharks indirectly maintain sea-grass and coral levels, and their population decline has been sorely felt by coral reefs.

The way forward in shark conservation isn’t simple. As much as “Jaws” demonised sharks, it also increased public interest and awareness, creating more funding for scientific research and conservation efforts. But with this widespread interest came an expectation of simplification for the overall public, whether that was “The Jaws Effect,” which demonised sharks, or in understanding how to conserve them, where nuance may be lost on either side, to the detriment of sharks.

The US this week has been praised for finally passing a bill that makes it illegal to “possess, buy, sell, or transport shark fins or any other product containing shark fins, except for certain dogfish fins.” However, this is exactly what some scientists and conservationists, like Dr. David Shiffman at Arizona State University, have feared.

While Shiffman is against finning – the practice of removing a shark’s fins and returning the rest of the animal to the water – in 2020, Shiffman advocated instead for the promotion of sustainable shark fisheries. He worries that a “fin ban” would impede science-based fishing quotas, even when examining non-threatened species. Many others worry that a total ban on shark finning in the US will only drive the trade deeper underground.

Much like in the movie itself, “Jaws” has generated a view of sharks where the animal itself is seldom seen, but often thought about, in general and murky terms. While it generated a huge amount of interest in sharks, it also brought about a rise in trophy hunting, and in well-intentioned conservation acts that, worryingly, might yet also prove to be a hindrance to shark research and conservation. Spielberg needn’t worry too much though about sharks being “mad” at him. If sharks do want retribution for their massive declines, he will surely be further down their hit list.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A Shark in Pelagic Waters. Featured Photo Credit: Daniel Torobekov.