2021 has seen Europe regress steadily into a wall building fervour, amidst a culture of anti-immigrant sentiment, and increased politicisation of migrants issues. Greece recently announced plans to extend its border wall with Turkey, and re-apply pressure on the EU to supply funds for that purpose. Physical borders also continue to be strengthened and maintained by Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary and others.

In October, 12 EU countries issued a joint request for the EU to prioritise the allocation of funds for the building of borders. The request was met with disapproval from the EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who asserted that “there is a longstanding view in the European Commission and in the European parliament that there will be no funding of barbed wire and walls.”

There was a suggestion that the EU might waver on this position however, after European Council President Charles Michel indicated support for the idea in November, during the recent Poland-Belarus border crisis.

Many criticised Trump's idea of building a wall.

But we have in the EU erected over 1000 km of walls over last 30 years to prevent #asylumseekers from coming.

1000km to look away rather than to show solidarity.

1000km of shame!

– @DamienCAREME #MigrationEU #EPlenary pic.twitter.com/sBqrtQzGTI

— Greens/EFA in the EU Parliament

(@GreensEFA) January 19, 2021

The EU currently however prefers to promote border protection through the funding of surveillance equipment and other cutting edge technology. A guardian investigation into EU funding of an increasingly advanced border enforcement project came to a dystopian conclusion. It described “a digital wall on the harsh sea, forest and mountain frontiers, and a technological playground for military and tech companies repurposing products for new markets.”

Although the EU’s continued commitment this year to withholding funds for the building of walls is beneficial to asylum seekers, 2021 has seen a staggering number of rights violations on Europe’s borders. Leaked reports suggested that in the first 6 months of 2021, Frontex, the EU’s border enforcement agency, deported a record-breaking 8,239 non-EU nationals.

On International Migrants Day in Berlin, #AbolishFrontex activists are taking to the street in the #b1812 demonstration, highlighting the involvement of Airbus and other companies in the deadly border regime. pic.twitter.com/PNzgw81PIa

— Abolish Frontex (@abolishfrontex) December 18, 2021

A Guardian investigation published in May this year claimed that “EU member states,” supported by Frontex, “used illegal operations to push back at least 40,000 asylum seekers” during the pandemic period, linking them to 2000 deaths.

The cutting off of migrant routes to Europe, and the failure to provide safer alternatives, have left many seeking more dangerous means of travel. In one incident in November, 27 people, including children and pregnant women, drowned to death near Calais attempting to cross the Channel.

A collaborative journalistic investigation, led by Lighthouse Reports, covered in detail by Impakter, exposed the use of EU funds to bolster a “shadow army” of masked soldiers operating across the West Balkans, engaging in illegal push-backs, forcing migrants back out to sea in perilous conditions. Push-backs involve the forcing back of asylum seekers into unsafe conditions, and are a contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights, as well as the Geneva Convention.

The EU has also failed to hold states accountable for their violations, still issuing no condemnation of Croatia’s systematic abuse of migrants at the border, even after a report from the Council of Europe was made public towards the end of year, revealing evidence of gross violence and sexual abuse.

Anti-immigration sentiments are fuelled by the same nationalism that threatens the break-up of the EU

The walls are only one part of a larger system of migrant abuse and hostility, including push-backs and physical violence, perpetrated on Europe’s borders. The measures, and the philosophy of insulation and outward hostility, have often been described as contributing to the creation of “Fortress Europe.”

The vision has been lauded by those on the right seeking to preserve nebulous ideas of European identity, and condemned by those on the left who see it as an economic and moral disaster. However, anti-immigration sentiment often goes hand in hand with euro-scepticism, both emanating from the philosophy of nationalism guiding a number of EU states, raising questions as to the unity of “Fortress Europe.”

Two of the countries involved in high profile anti-migrant campaigns, Poland and Hungary, have been in increased conflict with the EU this year over the supremacy of EU law, a principle that forms the backbone of the EU’s harmonisation philosophy. Poland’s ruling Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) party has been accused of pushing for an EU exit, dubbed “Polexit.” This trend has been much to the chagrin of Polish citizens, tens of thousands of whom took to the streets in October to protest in favour of EU membership.

Related articles: Big Emitters Spend Twice as Much on Borders Than Climate Finance | Asylum Seekers at the US-Mexico Border Face Continued Challenges Under Biden

Hungary likewise has been suspected of moving towards “Huxit,” spurred by Viktor Orban, who has described the EU as treating Hungary and Poland as enemies, and has been one of Europe’s most fervent proponents of EU-funded wall building. Orban also confirmed this week his commitment to ignore an EU court ruling, continuing to criminalise Hungarian lawyers and activists who help people file asylum claims.

The bill criminalising helping asylum seekers, issued in 2018, is referred to as the “Stop Soros” law, a reference to Hungarian billionaire George Soros, who has long been a supporter of left wing causes. Orban has accused Soros of funding a secret conspiracy to facilitate migration, contributing to global anti-Semitic conspiracies espoused by right-wing pundits across the world.

Poland also continues to develop its border wall, which cuts through the Bialowieza forest, threatening the destruction of local ecosystems. Whilst Poland is currently embroiled in a dispute with the EU over the rule of law, it has received little condemnation from the EU over its violations of international law.

Not once did the @EUCouncil express concern about human beings dying at the EU's borders or illegal pushbacks

Instead human tragedies are described with bureaucratic terms about ‘addressing routes’ and ‘returns policy’

No to fortress Europe #InternationalMigrantsDay #EUCO pic.twitter.com/ql7vjGdQJ7

— EUROPEAN TRADE UNION (@etuc_ces) December 17, 2021

The EU was largely supportive of Poland’s position during the Poland-Belarus Crisis, which saw the state engage in push-backs, even backing the restriction of asylum rights and the increased length of migrant detention. Several migrants, including children, have died as a result of the crisis, exposed to freezing conditions and cut off from aid.

Anti-immigration sentiment in Europe is tied to racist ideologies, espoused by prominent figures

Migration has repeatedly been linked to economic benefits for the country in which asylum seekers are allowed to settle. As pointed out recently in the Financial Times, migrants, although “only 3.4 per cent of the global population… accounted for 9.4 per cent of its gross domestic product.”

Anti-immigrant sentiment is however a phenomenon based largely on questions of identity, nationalism and racism rather than any real economic concerns. This is evidenced by the way in which European leaders seeking to clamp down on migration often appeal a greater culture war, and a desire to protect ill-defined values and identities.

Hungary’s Viktor Orban, seen often as a figurehead for Europe’s far-right, has repeatedly pushed his migration agenda through the use of Islamophobic rhetoric. He recently suggested that Bosnia would not make a good member state due to the presence of its 2 million Muslim citizens, feeding into a greater ethno-centric right-wing narrative about Europe’s identity.

Islamophobia narratives throughout Europe, and indeed the Western world, can be traced partly to “the great replacement theory,” originating in France. A recent poll in France suggested that 61% of French people believe that they are at risk of a “great replacement,” specifically due to the presence of Muslims.

The theory suggests that French people will be replaced by migrants from Europe and the Middle East, regions that were formally French colonies. It repackages old anti-Semitic ideas from the early 20th century, warning of the threat Jewish people represented to Europe.

France’s upcoming election choices include candidates who have doubled down on Islamophobia and anti-immigration sentiments, despite France holding a lower than average percentage of immigrants than most OECD countries.

WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT – Supporters of French far-right presidential candidate Eric Zemmour threw punches and chairs at several protesters wearing anti-racism T-shirts during his first political rally https://t.co/J19m7HELcV pic.twitter.com/pCYeRmZR9Q

— Reuters (@Reuters) December 6, 2021

An important, often overlooked factor in issues related to migration, is the effect of climate change in the poorest regions of the globe, affecting migration patterns. EU nations have historically contributed largely to the global total of carbon emissions. It is worth remembering that many migrants being turned away at EU borders are from countries that have been subjected to droughts and shortages of resources resulting from climate change.

Although progress has been made in recent years to reduce the EU’s carbon footprint, consideration must be given to the responsibility of EU nations to poorer populations affected by the activities of the world’s richest nations.

2021 has seen migrants face new legal challenges, physical threats, and more dangerous routes to the countries in which they hope to find asylum. The inordinate costs of wall building, Frontex operations and EU-funded surveillance equipment seems financially unjustifiable, given the economic benefits of incorporating asylum seekers into EU workforces.

More importantly however, Europe faces a moral dilemma going into 2022. Will it continue its hostility to migrants, riding a wave of nationalist and racist rhetoric that justifies state sanctioned violence at borders, or take its international obligation to asylum seekers seriously, and prioritise the humanity of vulnerable people over political games?

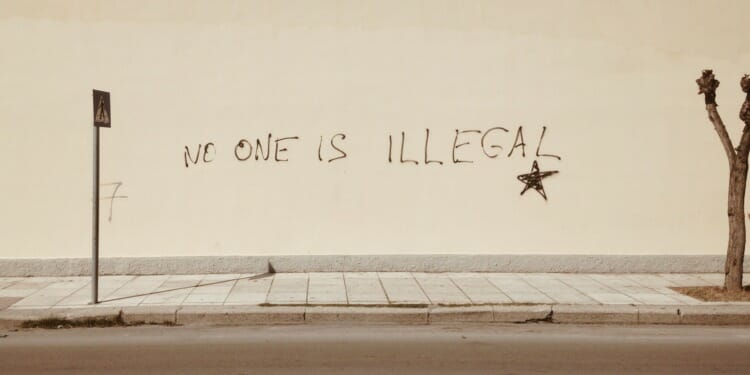

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: A wall in Greece, where a pro-migrant sentiment has been written. Featured Photo Credit: Miko Guziuk.