So far this year, 7,418 migrants and refugees have arrived in the Canary Islands. While 210 people lost their lives in all of 2019, there have already been over 250 deaths in 2021, according to the UN’s International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

The true numbers are almost certainly much higher. “Invisible shipwrecks,” where boats go missing at sea, suggest the actual figure could be up to eight times the IOM’s estimates, according to a report from the Spanish NGO Caminando Fronteras.

Caminando Fronteras highlighted that there were five times as many deaths in the first half of 2021 than there were during the same period last year. This is the highest number of deaths since the NGO began recording migrant deaths at sea in the region 14 years ago.

The Atlantic: A Dangerous Route to the EU

There are many complex reasons for this dramatic increase in deaths: the heavy impact of the pandemic on developing economies, the fishing crisis in Senegal, the continued war in Mali. But an obvious discrepancy in the data suggests that these deaths are due to a change in the way migrants are getting into EU territory.

The report from Caminando Frontera estimates that almost 2,100 migrants have died trying to reach Spain by sea between January and June of 2021. Of this number, the Atlantic route, from countries on the West coast of Africa to the Canary Islands, has claimed 1,922 lives, 91% of the total.

Related Articles: War on Migrants: Is Europe the Loser? | Refugees: Why they are not an economic burden

In part, the increased policing of the routes from Morocco and Libya by EU backed Libyan and Moroccan authorities has led to the renewed popularity of the dangerous Atlantic route.

In 2019, the EU allocated 140 million Euros to support Morocco’s efforts against irregular migration. In that same year fewer than 2,700 migrants arrived in the Canaries. In 2020, more than 23,023 made the crossing, overwhelming the reception infrastructure on the islands and leading to conditions that were deemed to violate migrant’s human rights.

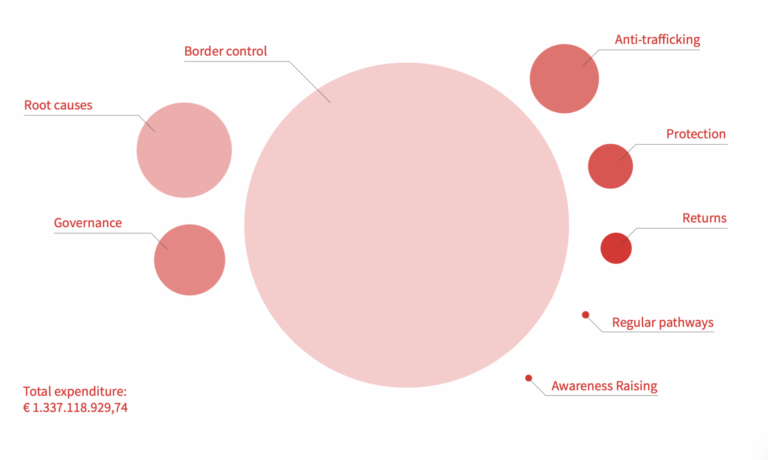

In the five years since 2015, €1.337 billion has been spent by the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, accused of ultimately trying to build a “big wall” between Europe and Africa. Amongst many other things, the fund provided border guard training in 20 African countries, and reconstructed the Libyan coast guard. Of this fund only 3% was used to develop safe and legal routes for migration.

In fact, these increased deaths show it has achieved just the opposite.

It seems that this renewed focus on a “big wall” in the Mediterranean is merely shifting the flow from the Mediterranean onto the Atlantic sea, where rubber dinghy’s leave Mauritania aiming for the tiny Canary Islands, sometimes ending up filled with corpses as far away as the Caribbean islands.

Building this wall between Africa and Europe has not stemmed the flow of migrants. As Hana Jalloul, Spanish secretary of state for migration, told the Guardian: “Migration is a historical fact and that’s not going to stop.”

Positive Migration Control as a Humane Solution

The denial of the basic facts of migration is handing desperate and vulnerable people into the hands of trafficking gangs, who use dangerously irresponsible types of boats to do crossings which lead to these tragic deaths. Policing, and other negative forms of control, deny the reality of the migrant’s struggle.

Migration is a historical fact and that’s not going to stop.

—Hana Jalloul

There is, for Hana Jalloul, a “need for an intelligent and multilateral approach to people-flows.” More positive, integrative forms of control are far from impossible, nor would they be hugely expensive.

Georges Soros, in his great article on the subject, has proposed a more humane way of dealing with the fact of migration, arguing that most of the building blocks for an effective asylum system are already available. A brief summary of his proposal runs like this:

- The EU sets a firm and reliable quota for migrant entries — between 300,000 and 500,000 a year;

- Countries with a high number of migrants must receive enough financial support to make migrant lives there viable; with a promise that in the next few years they will be part of the 300,000 allowed to make the crossing;

- Establishing the “voluntary balancing of supply and demand in other fields, such as with matching students to schools and junior doctors to hospitals. In this case, people determined to go to a particular destination would have to wait longer than those who accept the destination allotted to them. The asylum seekers could then be required to await their turn where they are currently located.

Such an approach, argues Soros, would be “much cheaper and less painful than the current chaos, in which inevitably the migrants are the main victims.” It would be more equitable too: Those who jump the line would lose their place and have to start all over again. “This should be sufficient inducement to obey the rules,” he writes.

Soros estimates a project of this kind would cost $30 billion, “less than one-half of one percent of total spending by its twenty-eight member governments.”

Clearly this would be fairly complex to manage, but it would avoid the tragedy of the thousands who drown every year behind the “big wall” the EU has built across the sea. It would be compassionate, fair, cheap, and treat migrants with the dignity they are currently denied.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: The Spanish coastguard intercepts a traditional fishing boat carrying African migrants off the island of Tenerife in the Canaries. Featured Photo Credit: UNHCR Photo Download.