I am Danish – and proud of it. But realistically, Denmark is the epitome of white privilege. The population is 90% white, highly wealthy and as such, very happy. This summer, Danes witnessed Derek Chauvin pressing his knee into George Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. As the international responded, so did Denmark – hosting a large protest and participating in the Black Out Tuesday trend on social media.

But as I witnessed my fellow white Danes posting Instagram stories of themselves proclaiming that “Black Lives Matter,” I couldn’t help but think of the overt as well as covert racism that has plagued, and continues to haunt Denmark. Now, when the international was watching and reacting, Danes thought it was time to act, and seemingly acting for only a brief moment.

Was this fleeting moment of action simply a perfect instance of white guilt?

Previously, I introduced the idea of guilt as a motivator for accountability and subsequent drive for change – a passing comment seeking to contemplate possible solutions to a seemingly impossible phenomenon. The term white guilt in itself is a simple concept referring to the feeling evoked when whiteness acknowledges its advantage as illegitimately taken.

White guilt is the bitter moment when white privilege is highlighted, not as some exceptional greatness that is naturally innate in white bodies, but as something stolen on an illegitimate premise. However, despite decades, even centuries, of raising awareness around racial injustice, whiteness struggles to see it, or simply rejects its existence. As the notion goes, if I cannot see it then it must not be true.

Reality is that whiteness is rarely under stress, as Sara Ahmed explained. In a world that inhabits whiteness, meaning that social spaces are predominantly white, it goes unnoticed – whiteness is not confronted, but merely the canvas. Contrarily, blackness or non-whiteness does not go unnoticed in a white world. It arises as a disorientation and is consistently enduring stressful encounters.

White guilt is the moment when whiteness is disoriented and at last, noticed. The moment of white disorientation sparks the stressful encounter that non-white bodies have always had to endure, whereas white bodies struggle in their reaction.

You have seen the struggling reaction. Reni Eddo-Lodge even compiled an entire book outlining why she would no longer talk to white people about race, exactly because of the reactions spurring when whiteness is confronted. She found that “making white people feel uncomfortable is impermissible,” and causes responses deflecting the issue away from whiteness.

Two common reactions develop when white guilt is evoked, and honestly, in my experience of being as white as it gets, I believe a large fraction of white people have encountered these reactions. Either whiteness becomes a prisoner of these guilty, shameful emotions. That is commonly the moment when one has to comfort a white person in despair over the harm done towards non-white bodies. Or whiteness seeks quick reparations. That is for instance the moment when whiteness participates in a protest without subsequent commitment to anti-racist work.

The strength of white guilt lies in its ability to personalise racism to the white body. Whiteness is the canvas in the western hemisphere – I reiterate, it goes unnoticed. With white guilt, it becomes noticeable and a visible problem to be scrutinised. By default, racism is internalised as an intimate issue for the white body, which could potentially motivate long-term commitments to change

At its core, is racism not in reality a white problem that non-white bodies suffer the grave consequences for? If that were accepted as the case, white guilt could therefore be the emotion that facilitates accountability of whiteness – as a cause of racism and therefore an essential agent of change. Whiteness as the causality of racism and a continued force penetrating racial violence, suffering and suppression, whether it is intentional or not. By the issue becoming personal, whiteness may finally act and change the various meticulous ways racism weaves through society.

The danger of white guilt is that it centers the emotions of whiteness as the feeling is heavily internalised, and heavily felt, to the extent of fully deflecting away from white complicity in racial violence and subsequent suffering. Instead, it becomes about the feeling, and how to get rid of the uncomfortability of complicity.

Reni Eddo-Lodge claimed that when whiteness is confronted by that guilt, “the response from white people is to shift the focus away from their complicity,” and there are vast amounts of research supporting that very notion.

In a study by Aarti Iyer, Colin Leach, and Faye Crosby, white guilt proved to be a self-focused emotion, which “leads to an overriding concern with making restitution to the disadvantaged.” They proposed that the self-focused nature of white guilt would seek quick compensatory acts for the harm done rather than consistent anti-racist commitments.

Guilt goes hand in hand with exoneration.

In his book, White Guilt, Shelby Steele claims that white guilt presents itself as a moment of vulnerability forcing black power to exploit this passing moment of white powerlessness. He explains it through the tale of a friend who engaged in the endeavour of expressing his suffering in exchange for a fraction of white guilt. In this case, as Steele explained, “the selfishly guilty white person is drawn to what blacks least like in themselves – their suffering, victimization, and dependency.”

Related Articles: BLM and BDS: A Relationship of Resistance | The Extensive Effects and Implications of the ICE Student Ban | How Racist is the American Political System?

Guilt drives white self-preoccupation and enforces black invisibility. As whiteness seeks repentance, blackness becomes victimized – and again, exploited by whiteness in the endeavour of exoneration. In those moments, it becomes nothing more but a victim of its own pain and struggle. Blackness is reduced to a legacy of black suffering when whiteness penetrates its guilt. That is an unequal transaction. Once again, whiteness stands with the privilege to repent and blackness is yet again the victim of white oppression.

The detriment of white guilt lies in its companionship with exoneration. White guilt thrives alongside a need for forgiveness – the absolution of guilt. This “urgency of repentance,” as Steele frames it in his book, seeks short-term solutions rather than long-term commitments to change.

The eagerness for exoneration leads to the giving of entitlements in a desperate attempt to repent one’s guilt. As seen in Denmark, citizens, at last, said no to racism, even though racism has prevailed in countless corners of the country with minimal objections for a long time. While action is indeed applaudable, can Danes today claim that real change is being pursued after its public display of commitment to anti-racist work this summer?

These global movements for racial change tend to lose momentum, and potentially it is because of that ephemeral moment of guilt that is absolved by urgent repentance.

Maybe, we need to introduce a new term – white accountability. Accountability for racism and accountability for changing whiteness and its continued oppressive and supremacist nature. Instead of being a prisoner of negative emotions in a pursuit for exoneration, whiteness could simply take in the sensation of accountability.

White guilt can act as a stepping stone – it may even be a vital component to white accountability. As a powerful, personal emotion, guilt makes racism intimate to the white person. No longer is racial oppression something ‘out there.’ Through guilt, whiteness acknowledges its positionality in relations to racism. That acknowledgement can incentivise honest accountability for centuries of dispossession, aggression and oppression of non-white bodies, and the continued penetration of such unequal racial relations.

The determining point is: what are you going to do about that guilt? As evident, most individuals seek urgent exoneration or become prisoners of their emotions. But by confronting that guilt, it can transcend to white accountability in the enactment of change. In the case of Denmark, instead of being momentarily involved, the defining moment lies in that confrontation with race and thus asking oneself – how am I positioned in relations to the issue of racial oppression?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

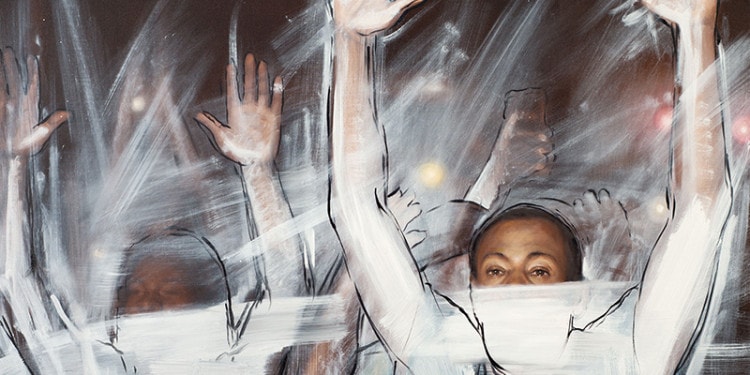

In the Featured Photo: Another Fight For Remembrance Photo Credit: Titus Kaphar

You can find Kathrine on Twitter or Linkedin.