The large man with the bald head and tattoos down his neck eyed me distrustfully. ‘Are you the writing lady?’ He moves closer so his sweat tickled my nostrils. His nipples protruded through a slightly grubby t-shirt, his belly looked about eleven months pregnant and he was wearing immaculate white designer trainers due to limited access outside. ‘Cos I’ve got a novel what I want to show you.’

He grins toothlessly and I notice that his head isn’t actually completely bald. He has a long thin plait at the side, sprouting from an otherwise shiny pate. ‘Want to come to my pad and I’ll show you.’

I explain that it’s against the rules for me to do that – as he probably knows – but that if he’d like to bring his novel down to the fish tank where I’m hovering, touting for business, I’d be happy to have a look at it. While he’s gone, I distribute home-made leaflets to men walking around the wing, advertising the various writing workshops I’m going to be running in the next few months. ‘Want to write?’ says the heading. A young very pale man with a shock of black hair that flops over one eye, takes one. ‘Always fancied penning a best-seller.’ He sniffs. ‘But I can’t read or write.’

I explain that it’s against the rules for me to do that – as he probably knows – but that if he’d like to bring his novel down to the fish tank where I’m hovering, touting for business, I’d be happy to have a look at it. While he’s gone, I distribute home-made leaflets to men walking around the wing, advertising the various writing workshops I’m going to be running in the next few months. ‘Want to write?’ says the heading. A young very pale man with a shock of black hair that flops over one eye, takes one. ‘Always fancied penning a best-seller.’ He sniffs. ‘But I can’t read or write.’

I’m ready for this one. ‘You don’t need to. We can make up stories in a group by telling them to each other.’ He doesn’t look convinced. Meanwhile, plait man is back, laden with loose un-numbered A4 pages covered in large black capital letters. I promise to read it by next week and come back to him. His face falls. ‘Aren’t you going to read it now?’

So I do and it’s good. Really good. It’s not so much a novel as a stack of prose about how revenge is pointless and it brings tears to my eyes. ‘My mate got knifed, you see,’ says plait man, ‘so I stabbed the geezer who did it. I phoned 999 but I still got done. When I get out, I just want a normal life.’

Related articles : OCEANA CEO – ANDY SHARPLESS INTERVIEW article by Anne-Hélène d’Arenberg VOICE POLLS – FELIX WINCKLER INTERVIEW article by Impakter

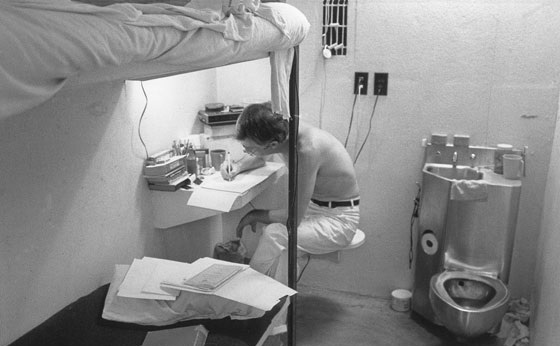

This is just a snapshot from a typical day when I was – until recently – writer in residence of a high security prison for men whose crimes have been front page headlines. Until I started my three year contract, I had never been inside a prison before. Indeed, I’m ashamed to say that it was only divorce and the need to pay my mortgage that led me to reply to The Guardian ad in 2007. When I got the job, I almost turned it down out of fear but before the end of my first day, I was hooked.

There are, typically, between 17 and 26 writers in residence in prisons every year. Most are employed by an organisation called Writers in Prison Network which places writers in HMPs all over the country. ‘My’ prison was unique in that it is a therapy prison set up in the 1960s as a social experiment. Men (who have raped, murdered and done GBH) are given intense counselling every morning both by specialists and also in their own small peer groups. So, for example, a rapist might challenge a murderer on why he took someone else’s life. There are also psychodrama sessions where men address an empty chair and imagine that a victim is sitting in it or a member of their own family. They then apologise to that ‘person’ for the anguish they have put them through. Although some of the men look just as you might imagine a prisoner to look like, others could easily pass for a suburban next door neighbour. I only once felt threatened by a sexist remark but immediately, my other men told the offender off. And no, I wasn’t accompanied by prison guards.

There are, typically, between 17 and 26 writers in residence in prisons every year. Most are employed by an organisation called Writers in Prison Network which places writers in HMPs all over the country. ‘My’ prison was unique in that it is a therapy prison set up in the 1960s as a social experiment. Men (who have raped, murdered and done GBH) are given intense counselling every morning both by specialists and also in their own small peer groups. So, for example, a rapist might challenge a murderer on why he took someone else’s life. There are also psychodrama sessions where men address an empty chair and imagine that a victim is sitting in it or a member of their own family. They then apologise to that ‘person’ for the anguish they have put them through. Although some of the men look just as you might imagine a prisoner to look like, others could easily pass for a suburban next door neighbour. I only once felt threatened by a sexist remark but immediately, my other men told the offender off. And no, I wasn’t accompanied by prison guards.

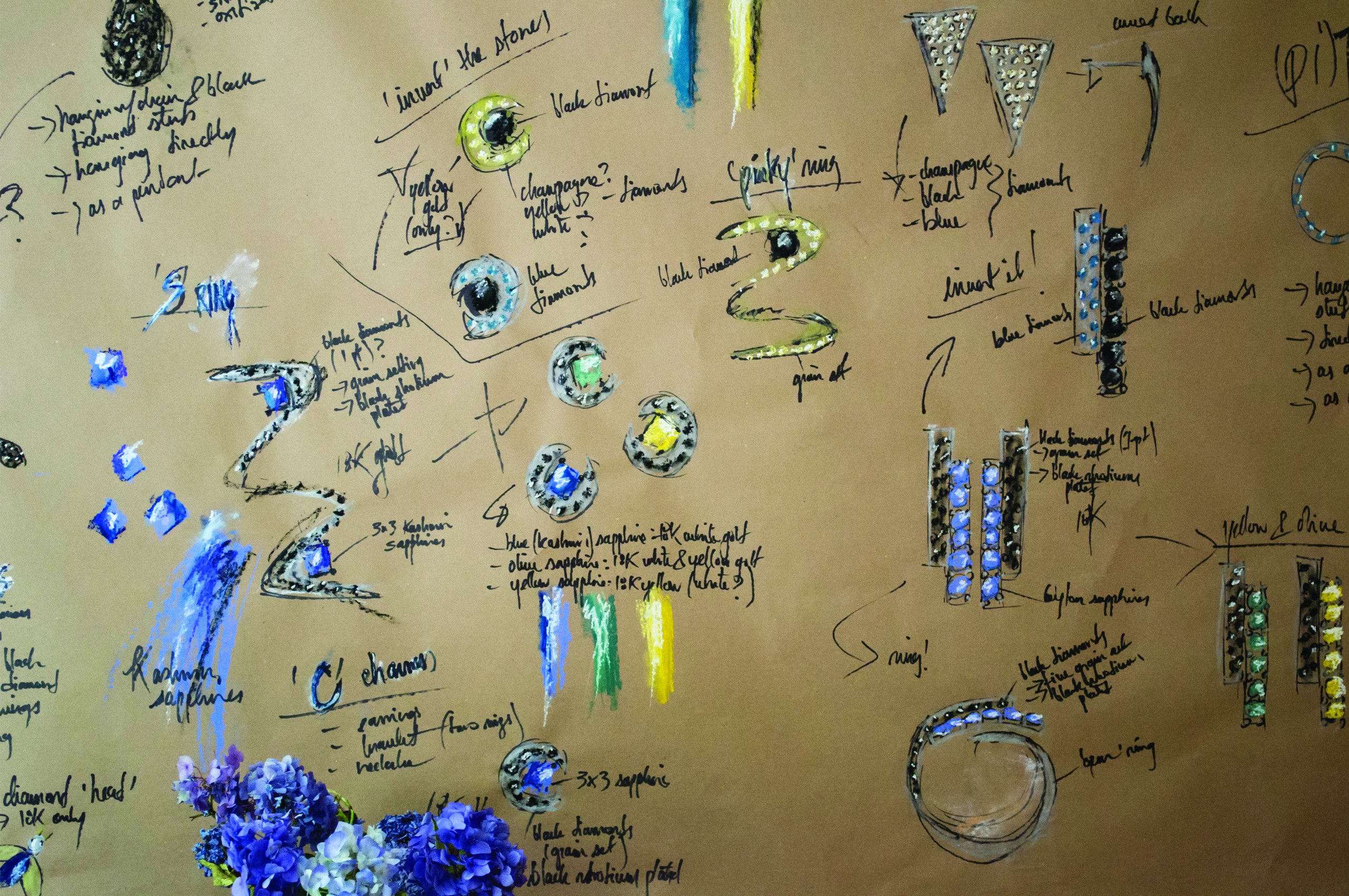

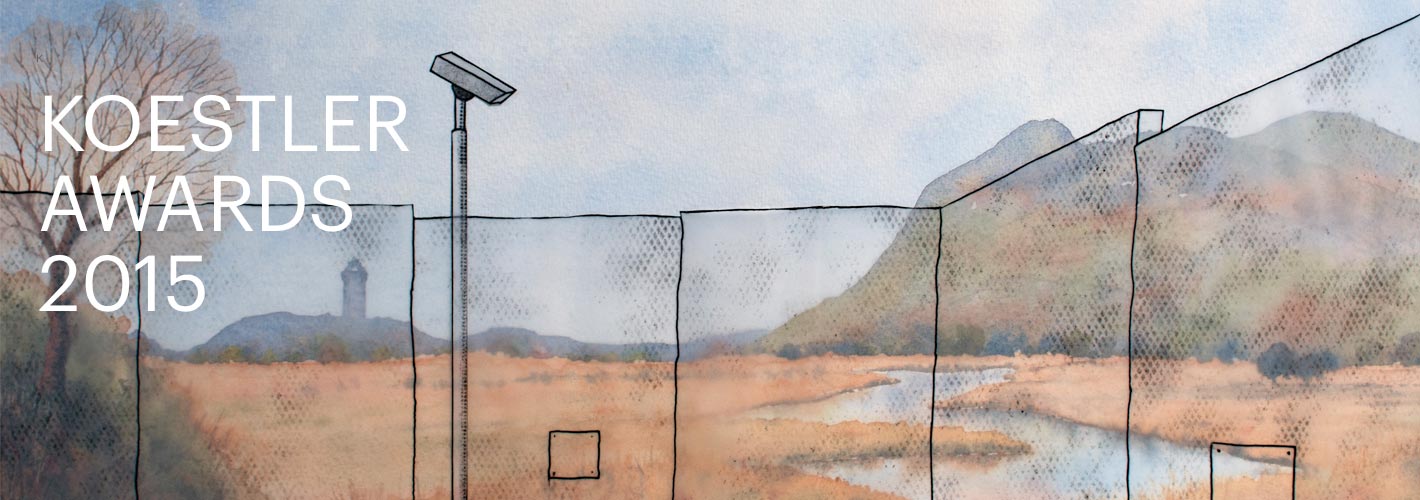

One of the roles of a writer in residence is to encourage men to write about their past as therapy towards a more law-abiding future. So I ran workshops on how to write letters, novels and short stories. Poetry is another favourite and so are life stories. I spent two days a week for a year, helping an armed robber to write his memoirs, entitled ‘Inside Out’. It won a prize in the Koestler Awards, a national competition for writers and artists in prison and mental institutions. I also published prayers and spiritual sayings from both prisoners and staff in a paperback called ‘The Book of UnCommon Prayer’.*

Due to my journalist contacts, I was able to rope in high-profile speakers. One of the most popular was Colin Dexter who, when asked how he got his inspiration, replied ‘From a very large bottle of malt whisky’. That went down a treat in a place where you can’t take in sugar sachets through Security in case the men make ‘hooch’ (an illegal alcoholic beverage).

I’m not going to pretend it was easy. One of the hardest bits was going through the gates every day and knowing that you weren’t going to smell fresh air for another eight hours. Then there was the overwhelming responsibility of locking gates behind you: if you forgot, you could be sacked on the spot. Men too could be ‘sacked’ from being in prison. One morning, I went in to find that one of my best poets had been ‘shipped out’ overnight. (Shipped out, means moved overnight to another prison.) His crime? According to one of the prison officers, he had been putting budgie poo in other men’s ice cream. (Some of the prisoners were allowed to keep budgies.) I lost another student because he was found to have porn under his bed and was promptly sent to another HMP (Her Majesty’s Prison).

People often asked if I felt threatened. Before I started work, I was scared of being hurt but when I got there, I found that words were a great leveller. I stopped being frightened of the men (and I believe they became more used to me in return) because we all loved words. My men didn’t have to come to my workshops. They chose to do so because they wanted to write. On one occasion, the usual room that we used was out of action. The only spare place was a room upstairs, next to their bedrooms (known as pads). This was usually out of bounds in case anyone was taken prisoner. However, the prison officer on duty said I could use the room ‘if I wanted to’. On this occasion, I was nervous. It would have been easy for them men to have taken me hostage. But if I’d declined, they would have known I didn’t have faith in them. Naively perhaps, I trusted them: they were men I’d known over the course of two years. So I ran the workshop upstairs next to their pads. And I was fine.

People often asked if I felt threatened. Before I started work, I was scared of being hurt but when I got there, I found that words were a great leveller. I stopped being frightened of the men (and I believe they became more used to me in return) because we all loved words. My men didn’t have to come to my workshops. They chose to do so because they wanted to write. On one occasion, the usual room that we used was out of action. The only spare place was a room upstairs, next to their bedrooms (known as pads). This was usually out of bounds in case anyone was taken prisoner. However, the prison officer on duty said I could use the room ‘if I wanted to’. On this occasion, I was nervous. It would have been easy for them men to have taken me hostage. But if I’d declined, they would have known I didn’t have faith in them. Naively perhaps, I trusted them: they were men I’d known over the course of two years. So I ran the workshop upstairs next to their pads. And I was fine.

Indeed, I often joked that I was treated better at prison than I was at home. Doors were held open for me and most people were very polite. There were just two exceptions when men on separate occasions swore at me. One apologised later. The other didn’t. However, I also had to make sure I kept my distance. As a psychologist friend warned me, some men might try to get me onside by flattering me. I had to remember that they were inside for a reason. Yet prison is also curiously addictive. It’s hard to get it out of my mind when you have been there; whether as an Inmate or an employee.

It’s been two years since my contract ended and, I confess, I miss both it and my men. However, in a funny way, I could never go back. When you’re on the outside again, prison seems scarier than when you’re In. Now I look back and wonder how I could leave the real world everyday and immerse myself in this strange environment when I would walk past murderers and rapists every day in the corridor before welcoming them into my class.

However, I haven’t lost all ties with the prison. Soon after I was ‘released’, I was asked to be the life story judge for the Koestler awards. These are a series of prizes awarded to men and women in prison and mental institutions for writing and art. My fellow-judge (a publisher) and I now spend a month very year, sifting through hundreds of entrants. It’s a task which is both daunting and also a great honour.

Yet one of my most moving experiences as a result of prison, came just a month ago when an email arrived out of the blue. It was from a former prison student who had somehow tracked me down on the internet. He told me that my classes had helped him to restore his confidence and that since being released, he had set up his own business, got married, had three children and was now leading a new life.

Yet one of my most moving experiences as a result of prison, came just a month ago when an email arrived out of the blue. It was from a former prison student who had somehow tracked me down on the internet. He told me that my classes had helped him to restore his confidence and that since being released, he had set up his own business, got married, had three children and was now leading a new life.

That, for me, was the best Christmas present of all. Although I’m not allowed to respond personally to former prison students, I was able to send him a reply through my old bosses, telling him how happy I was to hear of his news. I believe that what comes round, goes round. Not many of us expect to commit a crime. But sometimes it happens.

My role as writer in res did more than just help others. It also helped me: not just through a difficult divorce (by distracting me) but through giving me a new writing voice. Instead of writing romance alone, I now found I had a darker voice inside. And I’ve learned the value of humour because, as in any difficult situation, I found a lot of laughter behind bars too as well as tears.

Little note: We would love you to take a look at her book. We like it very much. The title is “The book of uncommon prayer”. Just get intouch with here to order a copy: janebidder@btinternet.com