Planning to send money from the U.S. or the U.K. to a family or friend in Africa?

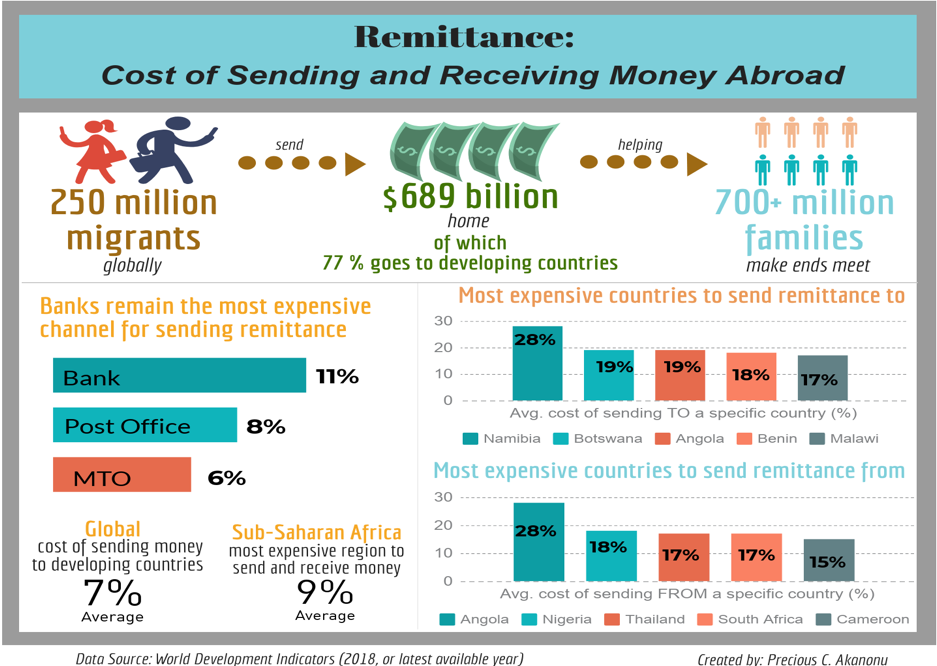

Remember to budget an additional 9% of that amount, on average, for the bank; and if sending from, say, Angola to neighbouring Namibia, make that budget 28%.

Many legal migrant workers and refugees experience the expensive, unequal and slow process of sending money to their loved ones.

Cross-border remittance is a very important component of livelihood for many households globally, especially for those in developing countries. In 2018, annual cross-border remittances amounted to $689 billion, of which 77% flowed to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), making it the largest source of external financing for LMICs (excluding China). This remittance flow to LMICs was four times the total amount spent in Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) at $163 billion, and nearly twice the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows at $462 billion per annum in 2018. For many countries like Haiti, Jamaica and Gambia, flows to each of these countries exceed 14% of their GDP.

Despite the proportion and relevance of remittance, the cost of sending these monies to LMICs remain high. On average, it costs $18 dollars to send $200 to someone in Africa. But this cost can be as low as just $1 for someone in Kazakhstan, and high as $58 dollars for someone in Namibia. The most expensive continent to send money to remains Sub-Saharan Africa, especially southern Africa (figure 1), with Angola-to-Namibia transfer topping the chart. The additional charges for cross-country money transfer cover the exchange rate margin, a transaction fee, and sometimes a cost-markup premium (in cases where the service provider has exclusive partnership).

Think these charges are small? Let’s sum it up: The total charge for cross-border remittances summed up to $30 billion in 2017 – this is equivalent to total non-military foreign aid of the U.S. Looking at the earnings of Western Union (WU), one of the most dominant money transfer operators (MTO) globally: WU completed 268 million remittance transfers with a value of $80 billion in 2016, out of which its total revenue exceeded $5 billion and net profit surpassed $250 million. Remittance is indeed expensive, for some more than others, and the remittance industry is indeed profitable!

Figure 1: Average transaction cost of sending remittances to LMIC (as a % of total charge).

Ultimately, the high cost of money transfers reduces gains from migration, especially for poor households in origin countries. If remittance costs were lower, much more disposable income can be made available to senders and receivers, especially in these poor countries. Recognizing the global value of remittance and the disproportionate burden for the poorest, the G8, G20 and the United Nations, among others, have committed to remittance cost reduction as part of global development agenda. The G8 and G20 committed to reducing global cost of remittances to 5% in 2009 and 2011 respectively, while the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets a cost reduction to 3% by 2030 under SDG 10 (target C) [on inequality].

Why has remittance remained disproportionately expensive?

Mainstream fin-tech companies like Venmo and Zelle have successfully built widely-accepted apps for person-to-person (in-country) money transfers, at absolutely no cost to the sender or receiver. However, these advancements have not found strong footing in the remittance industry. Few start-up companies like WorldRemit (2010), TransferWise (2011) and Revolut (2014) are taking the initiative to foster cheaper and faster money transfers to LMICs. But growth in this industry is constrained by a couple of factors, including entry barriers and low consumer education. At present, many national post offices have exclusive partnership arrangements with dominant MTOs, thereby preventing new players in the market. Also, consumers are not fully informed about alternative services in each remittance corridor to drive healthy competition and ensure that the cheapest service providers receive the most patronage.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

Containing Migration Is a Mistake

Skills For the Future: What Developing Countries Can Do Today to Benefit Tomorrow

Facebook’s Cryptocurrency Libra: What is it and Can it Fly

Moving Forward

Renegotiating existing exclusive partnerships and allowing new players operate can increase competition and lower remittance costs. Particularly, encouraging new players in the form of mobile/digital technology companies – to help displace high bank charges – can make remittance payment both cheaper and instant. Reports by PayPal and GSMA suggest that charges for money transfer via mobile technology is around half of the cost of remitting via MTO and banks. The 2018 World Bank and Bank of Albania study also reports that if half of the international remittances to Albania were sent via mobile money, beneficiaries could save up to $1.3 million per annum, while service providers could save up to $6.7 million. However, the growth of mobile remittance technology is constrained by important concerns related to Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) directives. In a bid to de-risk and comply with AML/CFT efforts, many international correspondent banks have closed the bank accounts of several MTOs.

Recognizing the nature of this challenge and opportunity, there is a need to review legal and regulatory frameworks surrounding remittances with the view of ‘managing’ rather ‘avoiding’ AMT/CFT risks. The G20’s recognition of this need led to the creation of the universal Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) in 2014; a 20-digit number to allow the global financial system know each client and what they own, thereby enabling them to track and manage risk in a low-cost and timely manner. However, the slow pace of collective action in its acceptance and usage by financial institutions globally has slowed the success of the LEI initiative and growth of remittance fin-tech. Looking forward, national financial regulators should require LEI as a mandatory prerequisite for applicable financial or non-financial businesses within its jurisdiction, as this 2017 article on Money & Banking points out.

In addition, consumer protection and enlightenment are essential for promoting the penetration and healthy usage of remittance fin-tech. In terms of protection, it will be paramount to ensure that customers understand the products and are aware of the risks, in addition to ensuring data protection, privacy and security. In terms of enlightenment, it will be vital to ensure standard prices comparison are listed for all MTOs in each country and corridor. Some remittance service providers display comparative prices of other providers, but they often do not cover all providers within the corridor – especially the cheapest alternatives. The G20 tried to address this challenge by introducing the Smart Remitter Target (SmaRT) that reports the 3 lowest cost service providers within each corridor. Unfortunately, it remains high-level and does not reach those who need it the most, particularly those in Africa and seeking to remit money. Initiatives that can better raise awareness for the available options within the reach and ‘language’ of the poorest LMIC households would be useful — startup and existing fin-tech companies should consider taking on this role in LMICs going forward.