There are several expectations and characteristics associated with what is imagined to be an ideal physician. If a profile of a physician existed it may consist of something like this: A high achiever that is considered extremely intelligent, empathetic and yet maintains a professional distance. The ideal physician always makes sound decisions under extreme pressure such as staying awake countless hours while still providing excellent care to patients.

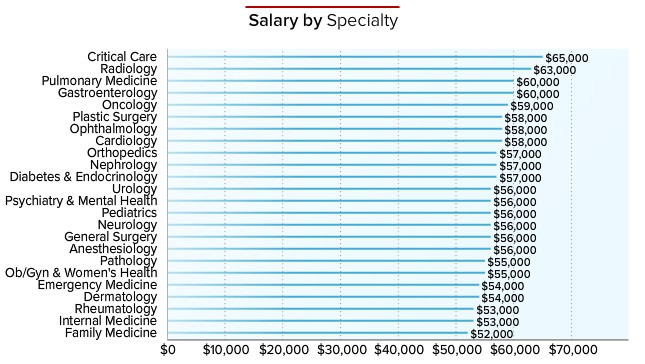

The ideal physician also assumes the huge debt load that their education requires while working eighty hours a week on an average resident salary of $56,000. The ideal physician is the ultimate problem solver who never needs support and never breaks down. In essence, physicians are expected to be perfect. These requirements seem insurmountable and impossible to achieve. Is it then a surprise that an entire size of a medical school graduating class commits suicide each year in the United States?

Dr. Jack Marrow* is a physician that chose not to use his real name due to the delicate nature of what might be discussed in this interview. Some physicians are hesitant to share highly sensitive viewpoints in fear that they may be perceived as weak or incapable. Dr. Marrow spent nearly two hours sharing his journey of medical training me.

Dr. Marrow was at the top of his high school graduating class. He came from a family that is all high achievers. As a child, he was expected to not only maintain excellent grades, but also proficiently play a musical instrument. He was accepted to an Ivy League residency program and was among peers with similar intellectual abilities.

Dr. Marrow chose to specialize in internal medicine because he wanted to provide empathic care to a varied patient population. Once he finished training, Dr. Marrow chose to become a hospitalist. As a hospitalist, he only saw inpatients that are acutely ill. He is expected to make quick decisions under extreme conditions. He worked eighty hours a week and was forced to cover patients when other doctors called out. He stayed awake countless hours and had to provide excellent care to his patients and the ones he was covering. As a way to put his stress into perspective as a medical student, an attending once told him that he was no longer the smartest person in the class, so stop trying so hard.

Related articles:”WHEN CHILDREN NEED US MOST, WE CAN DO BETTER”

“THE TRUTH ABOUT BURNOUT AND SUICIDE AMONG PHYSICIANS”

This statement did not discourage him or lessen his drive to be the best at what he does. Dr. Marrow comes from a loving family of four and his parents were not considered wealthy. He went into debt to pay for medical school and entered an area of medicine that does not pay as well as others. Dr. Marrow left the practice of medicine as a full time hospitalist and accepted an administrative position as a reviewer of standard medical exams. He had the wherewithal to change positions before he experienced suicide ideology. He recognized his bout with burnout and entered a better quality of life as a way to preserve his mental health.

According to Dr. Marrow, he really enjoyed medical school and residency. When pressed for more information, however, he relates a humiliating pimping example he endured in medical school during his OBGYN rotation. Pimping places the doctor on the spot by asking a series of questions to mirror a real life patient situation. The attending was relatively young and he asked Dr. Marrow a question regarding the four vital signs. Dr. Marrow froze and could not provide her with an answer. He is convinced that the intention of the attending was to embarrass him rather than teach him how to think under pressure.

Despite this, Dr. Marrow is a supporter of pimping and believes that it helps junior doctors to think under pressure. The difference, he explains, between the pimping he experienced, as a medical student to the pimping he is encouraging is intent. If the attending or senior resident frames the questions in a positive and supportive tone, then the subordinate is less likely to panic or feel singled out. The purpose of pimping according to Dr. Marrow is to build quick thinking skills that are vital when caring for patients, not showcase a power struggle between senior staff and junior staff. He also feels it is an excellent opportunity to demonstrate the subordinates knowledge to senior physicians.

Dr. Marrow claims that he did not witness many peers experiencing negative behavior from attendings. He describes himself as an introvert, so if he were to feel overwhelmed or in need of support, he relied on his peers. When asked if reaching out to an attending was something he did, he said no and as an afterthought he said it would have been perceived as a sign of weakness. When pushed further on the point of whether his peers felt burnout or worst, suicide ideology, he vaguely remembers a resident who left the program due to drug addiction.

He goes on to say that he found out about this individual sometime after the resident left the program. As he remembers this person, he initially commends the discretion this resident received, but then retracts and points out that he did hear about the resident eventually. Due to the constant exposure to highly controlled medications, a physician that is addicted to drugs is at high risk for relapse. An addict is sometimes perceived as weak with an inability to control urges. A physician that is an addict is often shamed or shunned.

Dr. Marrow’s residency program made no attempt to assist the other residents to process a peer in distress. Instead, the attendings put together a seminar to assist residents with stress management. Is there a connection between the leaving of the resident and the timing of the seminar? There is no way to know for sure.

Photo: Estimated salary by specialty

Dr. Jack Marrow met managing the stresses of medical school and residency training with ease. He loved all aspects of medicine and he wanted to learn all that is necessary to be a learned physician. There was never an aha moment for Dr. Marrow when choosing a specialty. He loved caring for patients from different backgrounds and with various conditions. He loved the challenge of figuring out what ailed them and how to find answers. This constant sense of wonderment was in the field of internal medicine for Dr. Marrow, specifically as a hospitalist. This decision to specialize in internal medicine was met with little resistance from his peers and attendings.

The only person ironically that voiced some concerns about Dr. Marrow’s choice in specialty was his mother. The Marrow family experienced some turmoil when Dr. Marrow’s father was laid off for nearly two years and his mother was forced to maintain the family of six on a music teacher’s salary. As such, his mother made sure that each of his children was self reliant and not dependent on one salary to support a family. Dr. Marrow’s mother shared her son’s desire to specialize in internal medicine with a family friend who is a neurosurgeon. The friend disclosed the severe pay difference between a neurosurgeon and an internist. Dr. Marrow chuckles when relating this story, since it was the only time his mother ever gave her opinion regarding his career.

Internal medicine is an area of medicine that is often considered unchallenging and not for doctors that are exceptionally intelligent. Some attendings discourage their star subordinate to pursue such a specialty. Dr. Marrow never adopted that thinking and was actually encouraged to pursue his dream to become an internist as a hospitalist. As a hospitalist, he will have an array of patients in an acute environment and not have to manage an office setting. The hospital will provide him with the support staff needed to safely care for patients and file all insurance claims. He will divide his time working on service, teaching, and conducting research. Dr. Marrow loves teaching, which he associates to his mother’s influence. Dr. Marrow only applied to positions at teaching hospitals, thus he was set on his decision in choosing to become a hospitalist.

After seven years of being a hospitalist at a very prestigious teaching hospital, Dr. Marrow made the decision to leave the full-time practice of medicine and took an administrative position. Dr. Marrow was simply burned out. As he relates it, the moment when he knew it was time to change jobs was due to a clerical error. He claims that because of all the overtime he was forced to accumulate, he had several weeks of vacation time owed to him. When he realized that this time was accidentally eliminated, he went to investigate how to rectify this matter. As he describes this point, Dr. Marrow reflects and admits this may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back. When he approached the individual and pointed out this error, he was met with such hostility that he realized in that moment that it was time to leave his current position. Dr. Marrow ponders that if the clerk admitted to the error he might have been appeased.

As a hospitalist, Dr. Marrow was not considered a source of revenue for the hospital. He was not performing any procedures, no invasive testing was performed, and he only provided a level of care that is deemed as maintenance. Due to this lack of revenue ability, the hospital would provide more emphasis on other departments that were able to increase revenue for the hospital.

Photo Courtesy: Flickr/Phalinn Ooi

During his time as a hospitalist, most of his time was spent on the floors rather than teaching. Dr. Marrow felt over worked and under appreciated. During this time, he was approached by a colleague to review responses to a standardized test, that each physician must take in order to practice medicine in the US. Dr. Marrow enjoyed the experience, but never thought of it as a career. This same colleague asked him if he would consider coming to work full-time as a reviewer.

He loved medicine, he loved treating inpatients, he worked countless years to become a doctor, why would he leave all that behind? The timing of the new opportunity and the clerical error was the perfect storm for him to make a significant career change. Internists are one of the highest rated specialists that experience burnout. Curiously, one of the lowest rated specialists that experience burnout is neurosurgeons. Dr. Marrow believes there are certain personalities that are attracted to specific specialties. Individuals that are high intensity and power driven tend to be attracted to such specialties. Even in medical school, Dr. Marrow observed that like-minded students would associate with each other and inevitably would wind up in the same specialty.

These high-intensity, power-driven physicians thrive on poor life/work balance. These physicians embrace and expect to work under extreme work conditions. They are also the highest paid and valued at hospitals. The idea of complaining about being overworked or under-paid is not a consideration. These specialists work hard, but are nicely paid and a valued part of the hospital system. Dr. Marrow now reviews exams, works once a week, as a hospitalist in an emergency department, is a husband, and father of two children. He is very aware about his experience with burnout and has a reflective view of medicine.

As a junior attending, he was extremely overwhelmed by not having a safety net. As a medical student and resident, he was always able to rely on someone above him to review his work or bounce questions off of when he had concerns. When he became an attending, he started to experience decision fatigue. All of his patients were under his complete authority and he was fully licensed to make final decisions on his patients. It was not until three years of being an attending that he felt completely comfortable as a hospitalist.

Dr. Marrow appears to have a very stoic view of how he was trained. When the grave statistic of the suicide rates among medical students was brought to his attention and asked why he thinks this is happening, he answers, “As an attending, the one thing you realize is that you do not always have the answers to fix things.”

_ _

*Name has been changed