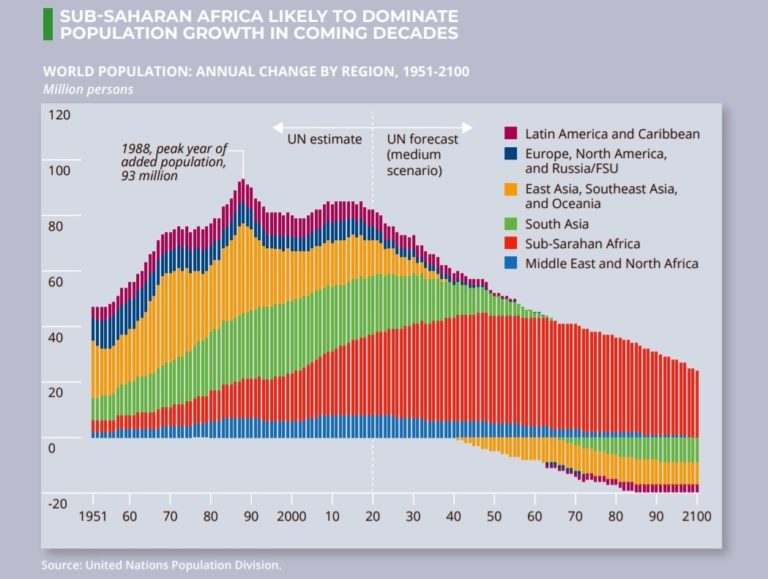

In a just-published “Global Trends” report subtitled “2040: A More Contested World“, produced by the National Intelligence Council (NIC) for President Biden, we learn that 20 years from now, the world will be a far hotter and more desperate place. With 1.4 billion more people, mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia, for a total of 9.2 billion while increasingly weakened Western democracies face rising flows of migrants. As diplomatically phrased in the report’s subtitle: It will be indeed “a more contested world”.

Should we believe this dire prognosis?

The report is of course based on solid analysis, obviously using American intelligence data but also resorting to reliable external sources. For example, for demographic projections, the report uses UN projections:

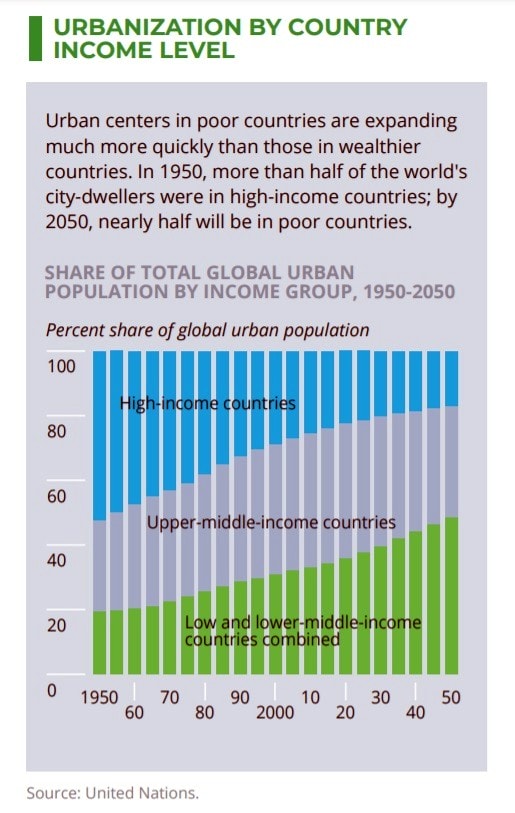

Also, the world will be increasingly urbanized, with two-thirds living in cities by 2040, up from 56 percent today. And this is how extensive urbanization will be depending on a country’s level of income and again the source is the United Nations:

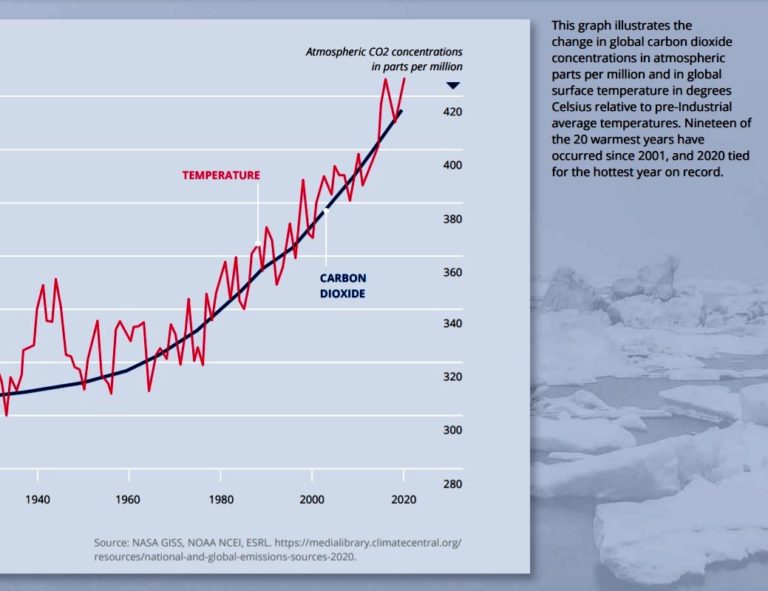

The sources for data on health, education and income inequality likewise are the best available, and so is the data on climate change. For example, this graph illustrating the change in global carbon dioxide concentrations is sourced from NASA and NOAA:

For Stewart Patrick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of “The Sovereignty Wars: Reconciling America with the World” (Brookings Press: 2018) we should believe this report, and the Biden administration should pay attention to it. In an article on World Politics Review reviewing the report, he noted that the “challenge, as always, will be to capture the attention of senior policymakers who could benefit from its long-range perspective, but are slaves to the tyranny of the here and now.” And to conclude: “If the Biden administration is serious about strategic planning, it would do well to commission a government-wide response to the report’s eye-opening findings.”

The findings are certainly “eye-opening” and are coming from a highly reliable source. Global trends reports have been produced by U.S. intelligence every four years since 1997 and this is the 7th edition. They are intended to “bridge” the US intelligence community with Washington policymakers, providing the incoming president a long-term view to assist in the elaboration of American foreign policy.

But is the US intelligence community really independent from politics? Stewart Patrick is convinced that it is. As he notes: “Although undertaken during the Trump administration, the report lacks any partisan hue, a testament to the independence and integrity of U.S. intelligence professionals.”

There is indeed proof of intellectual independence:

It is the First U.S. Intelligence Report that Sees Climate Change as a “Global Trend”

That is perhaps the best proof of independence, the fact that this is the first report of its kind to include climate change as a “global trend” – going right in the face of President Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Climate Agreement.

For climate activists, there may be not much news in the report’s findings in this area: Climate change is described as an “inexorable force that will transform world politics” noting that the past 10 years have been the hottest on record and each of the last five decades hotter than the previous one.

But the fact that climate change is taken as a major factor determining our future – something no previous report had done – does change the tenor of the predictions. And hopefully marks the beginning of a new political era as America may finally “wake up” to the challenge of global warming.

Let’s take a brief look at what the report says. It analyzes four “core areas” where it has identified global trends – which are termed “structural forces” manifesting in (1) Demographics and Human Development; with a special section for Future Global Health Challenges (call it the pandemic effect); (2) Environment; (3) Economics; and (4) Technology.

What is most interesting is the identification of five themes – five drivers of change – that crisscross the report and “underpin the overall thesis”:

- shared global challenges: they include “climate change, disease, financial crises, and technology disruptions” and are “likely to manifest more frequently and intensely in almost every region and country”;

- increased political fragmentation: “Paradoxically, as the world has grown more connected through communications technology, trade, and the movement of people, that very connectivity has divided and fragmented people and countries”;

- disequilibrium: “There is an increasing mismatch at all levels between challenges and needs with the systems and organizations to deal with them” and the international organizations (read: the UN, the EU etc) are “poorly set up to address the compounding global challenges facing populations” as shown by the COVID-19 pandemic that has “provided a stark example of the weaknesses in international coordination on health crises and the mismatch between existing institutions, funding levels, and future health challenges”;

- greater contestation at all levels, from local to international, as “many societies are increasingly divided among identity affiliations and at risk of greater fracturing” and . “as a result, politics within states are likely to grow more volatile and contentious, and no region, ideology, or governance system seems immune or to have the answers”;

- Adaptation: this is seen as “both an imperative and a key source of advantage for all actors in this world” and it will appear in all four “core areas”, as all countries will need to adapt to the changes and those able to adapt better and faster will come out the winners.

What “Adaptation” Really Means

Of the five themes, “adaptation” is by far the more innovative and interesting concept here. Consider examples put forward by the report:

- Climate change: it will force “almost all states and societies to adapt to a warmer planet” but while some measures are inexpensive (like restoring mangrove forests or increasing rainwater storage) others are complex and costly (building massive seawalls and coastal population relocation) and not every country will be able to do it; that the cost on developing countries will be hard to bear is of course nothing new and was, for example, the main finding of a 2018 report commissioned by UNEP to Imperial College Business School’s Centre for Climate Finance & Investment and SOAS University of London:

- Aging populations: China, Japan, South Korea and Europe with highly aged populations will “face constraints on economic growth in the absence of adaptive strategies, such as automation and increased immigration” – in other words, either accept migrant labor and integrate them in the society or replace local workers with robots (automation);

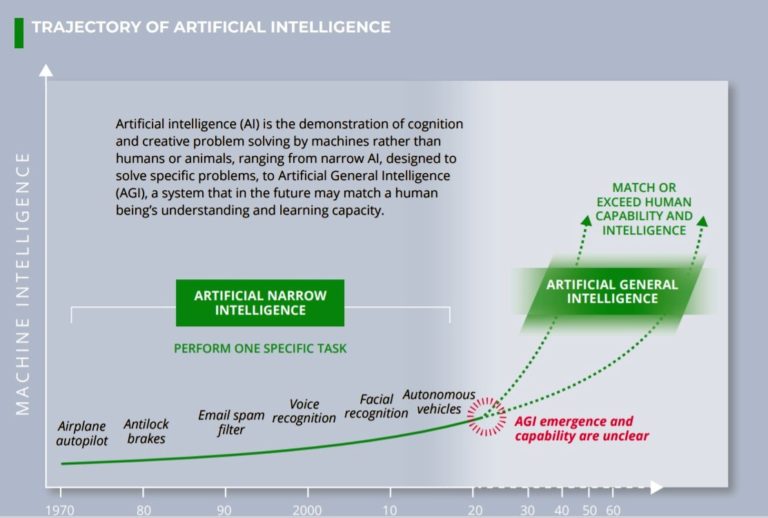

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): countries “able to harness productivity boosts from artificial intelligence (AI) will have expanded economic opportunities that could allow governments to deliver more services, reduce national debt, finance some of the costs of an aging population, and help some emerging countries avoid the middle-income trap” – in theory; but in reality, because AI is unevenly distributed, it is “likely to reveal and exacerbate inequalities”.

What is most exciting are the alternative scenarios presented for 2040. To construct them, the report authors tried to answer 3 questions: How severe are the looming global challenges? How do states and nonstate actors engage in the world, including focus and type of engagement? Finally, what do states prioritize for the future?

Here are the five scenarios that emerged in accordance with how these questions are answered.

(1) Renaissance of Democracies

This is the world seen through pink lenses: There is a “resurgence of open democracies led by the United States and its allies”; technology is advancing rapidly on the wave of public-private partnerships of the kind Mariana Mazzucato calls for in her book “Mission Economy: Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism”. And this is happening in both the United States and other democratic societies, Europe, Australia, Canada etc.

As a result, the global economy is transformed, “raising incomes, and improving the quality of life for millions around the globe”. Societal divisions are “eased”, trust in democratic institutions is “renewed” while things are falling apart in Russia and China: “years of increasing societal controls and monitoring in China and Russia have stifled innovation as leading scientists and entrepreneurs have sought asylum in the United States and Europe.”

(2) A World Adrift

The developed world is adrift, paralyzed by political polarization, slow (or no) economic growth and rising income inequality. China remains a world power but is unable to exercise leadership as it “lacks the will and military might to take on global leadership, leaving many global challenges, such as climate change and instability in developing countries, largely unaddressed.”

(3) Competitive Coexistence

The world is bi-polar: China on one side, the U.S. on the other. Trade between the two ensures economic coexistence and a (precarious) political balance is maintained. There is “e competition over political influence, governance models, technological dominance, and strategic advantage”, none of which ends up in war.

Global problems are “manageable” but some issues are ignored (or set aside) like climate change.

(4) Separate Silos

The world is divided into “several economic and security blocs of varying size and strength, centered on the United States, China, the European Union (EU), Russia, and a couple of regional powers”. Since these blocs are “focused on self-sufficiency, resiliency, and defense”, information flows and trade channels tend to be easily disrupted.

This is a hard world for developing countries to navigate: They “are caught in the middle with some on the verge of becoming failed states.” Again some major global issues are set aside, like climate change.

(5) Tragedy and Mobilization [of Europe and China]

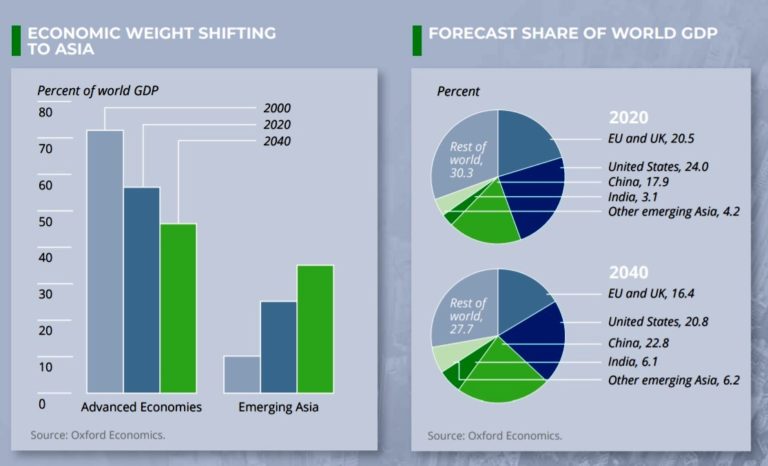

With this somewhat misleading title, the report authors are in fact imagining a future where an unexpected “global coalition” has emerged: Europe and China – but not the United States. This scenario takes into full the economic power shift from “advanced economies” to “emerging Asia” that has been taking place right under our nose, as depicted by Oxford Economics:

What happens is remarkable: This “global coalition, led by the EU and China working with nongovernmental organizations and revitalized multilateral institutions, is implementing far-reaching changes designed to address climate change, resource depletion, and poverty following a global food catastrophe caused by climate events and environmental degradation.”

So the tragedy is caused by climate change and environmental collapse, and the response comes from the United Nations and other multilateral organizations with the support of Europe and China, with both the public and private sectors involved.

In this world where the United States is absent, countries act in a commendable moral way: “Richer countries shift to help poorer ones manage the crisis and then transition to low carbon economies through broad aid programs and transfers of advanced energy technologies, recognizing how rapidly these global challenges spread across borders.”

How to Get the U.S. To Re-enter Global Politics

Clearly, the absence of the United States in this scenario is something President Biden might (must?) seek to change.

To change it means the U.S. should take the lead in supporting the United Nations and other multilateral organizations and push for the application of international treaties and agreements, starting with the Paris Climate Agreement.

Biden will shortly announce his climate change goals, hopefully setting the United States on a new course of climate action. And that would imply a radical change to scenario #5 should the U.S. join Europe and China in addressing climate change and also a range of other global issues. As I write, Biden has been beaten to the post by the European Union that has just announced its ambitious climate goals, reaching what is generally viewed around the world as a “major climate deal“.

In particular, there are a number of international norms that would need to be worked on as they are not accepted in many regions and/or countries. The report summarizes the state of affairs in a telling graph that sets out the “outlook for international norms”:

Reading the above through the lens of the Biden Administration, it would seem that even the norms labeled as “least likely to be contested” are not however norms accepted by the U.S., particularly the one labeled “International criminal accountability for mass atrocities”. It is a fact that the U.S. (under President Bush) never joined the International Criminal Court (ICC) and it is unclear for now whether or when it will rejoin.

But a first step in the right direction has been taken: Two weeks ago, the U.S. rescinded sanctions against the ICC. On April 2, 2021, Biden revoked a June 2020 order by then-President Donald Trump authorizing asset freezes and entry bans to thwart the ICC’s work. This opens the way for President Biden to do what human rights activists judge to be the right thing, i.e. support the “global court of last resort”.

How Much Confidence Should We Have in the U.S. Intelligence Prognosis?

My take after reading this report is that like any attempt to “read the future”, it is a highly uncertain exercise. Some things simply cannot be foretold. The report authors are well aware of this too. For example, when it comes to Artificial Intelligence, this is how they see it:

Indeed, AGI emergence is totally unclear and the subject of vigorous debate among experts.

Likewise, political outcomes are often unpredictable. The only thing that is certain is that they will change over the next 20 years. For example, it is not likely that the level of personal power currently achieved by several of the world’s major autocrats, from Putin to Erdogan, Orban, or Duterte will remain unchanged as they inevitably age and make more enemies. Whether their regime will survive will depend largely on the strength of the opposition. If the opposition is weak or disorganized, the autocratic regime will persist, as most recently illustrated by the example of Venezuela.

This said, making an effort to identify the major challenges ahead, taking into account every possible source of reliable information is a worthwhile exercise that helps to clarify the issues. One may only hope that politicians in Washington and high-placed managers in the Biden Administration will take a close look. And as there is also a series of interesting regional analyses, one would hope that interested citizens from across the world will also read it. What U.S. intelligence thinks about the rest of the world is always going to be an eye-opener even if one disagrees with what they say.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the Featured Image: Standing Watch 24/7: NCTC Operations Center Photo by Jessica Hrabrosky, Office of Strategic Communications