Zika’s exponential spread has much of the Americas panicking about how to handle this new epidemic. Countries from Brazil to the US have responded in many ways, but some of these responses have resulted in human rights violations.

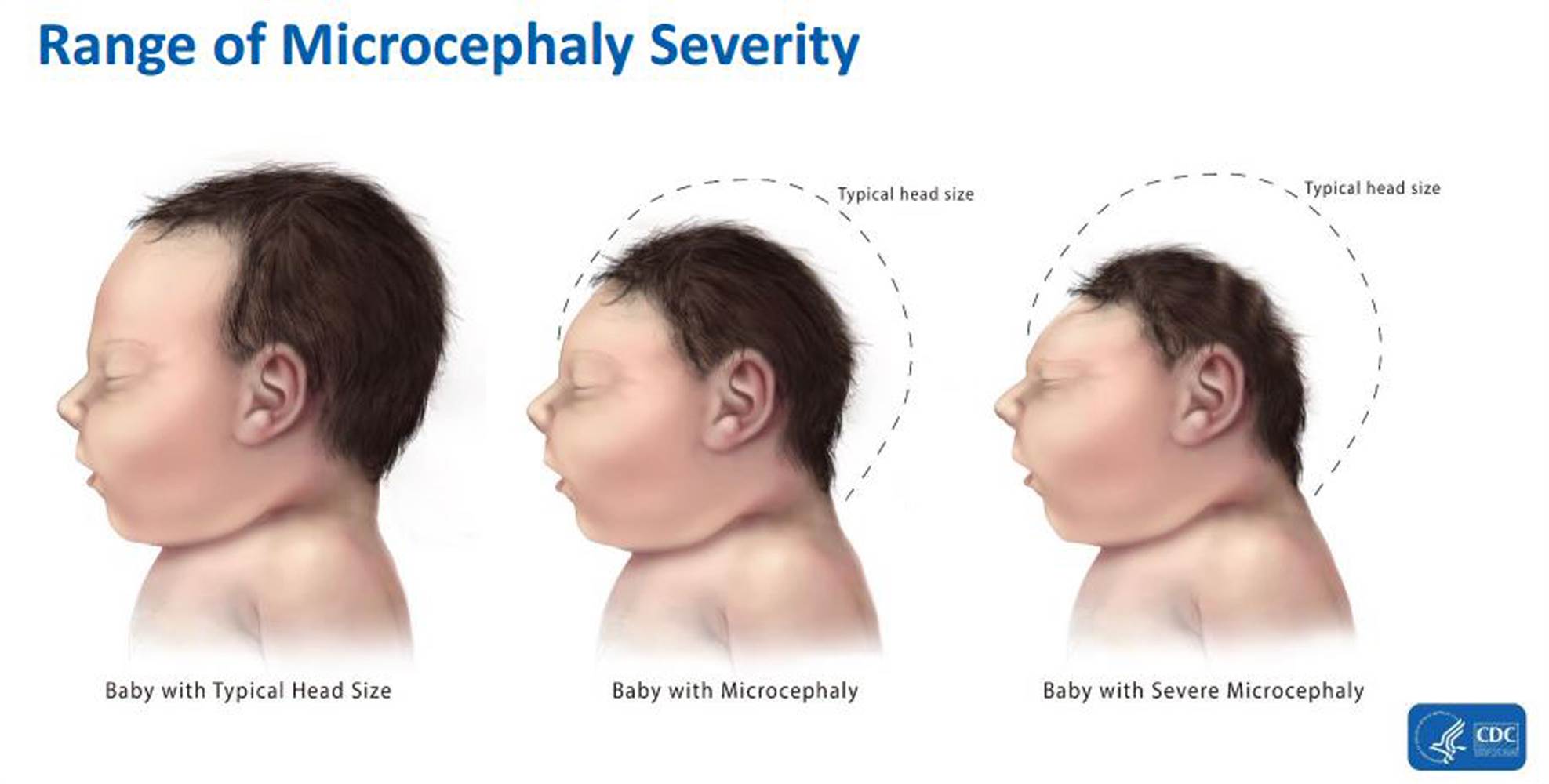

Zika may just be the new buzzword in epidemiology and public health research. Currently, Central and South American countries are being ravaged by the mosquito-borne virus that has been linked to rare diseases in vulnerable populations – and these resulting diseases are a much bigger deal than the symptoms of Zika itself. Whether Zika is correlated with microcephaly, a disease which causes abnormally small heads and developmental issues in babies, or with Guillain-Barré disease, an autoimmune disorder associated with paralysis, Zika is making rare diseases more common in the Americas.

In the graphic: Comparisons among babies with a typical head size, microcephaly, and severe microcephaly. Graphic Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Microcephaly can occur from a range of issues such as malnourishment, alcohol consumption while pregnant, diabetes, genetic abnormalities, and infections like German measles, toxoplasmosis, and cytomegalovirus. The CDC has warned pregnant women not to travel to the following countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, and Venezuela. They also recommended that if you are pregnant and have traveled to any of those countries that you immediately get screened for the virus itself.

Recent studies have provided more evidence that the relationship between Zika and microcephaly may be causal, and that Zika can cause not only microcephaly in newborns but also stillborn births. The increase in microcephaly and Zika virus infection is also indicative of the complications that can occur within the first trimester of pregnancy, as most of the research deals with examining pregnancies that reported symptoms of Zika during the first trimester of pregnancy. Researchers now say that the actual percentage of pregnancies that will result in microcephaly for those pregnant women infected with Zika during their first trimester of pregnancy is 1 percent.

Related articles: “IS BREASTFEEDING ALWAYS BEST?”

“REVAMPING PARENTAL LEAVE POLICIES IN THE U.S.“

In terms of fetal development during pregnancy, the first trimester tends to be the most crucial, as many of the organs including the brain and spinal cord form during this time. Various bodily systems continue to develop and are susceptible to malformation due to disease, alcohol, drugs, and certain medications. These malformations can lead to microcephaly.

In the photo: Brazilian mother doing physical therapy with her baby born with microcephaly. Photo Credit: Ricardo Moraes/Reuters

In the photo: Brazilian mother doing physical therapy with her baby born with microcephaly. Photo Credit: Ricardo Moraes/Reuters

In addition, one recent study provided evidence linking Zika to higher rates of the rare disease Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause paralysis and neurological complications over a 4-week period. Patients tend to complain of overall weakness, areflexia (the absence of reflexes to stimuli), and sensory disturbances. While other viruses like West Nile, Japanese encephalitis, chikungunya, and dengue have already been linked to Guillain-Barré, this study showed that the effects were much more intense for those with Zika virus.

Economically, Brazil has been living on a prayer in recent years and Zika is not helping matters. With multiple international organizations like the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advising people not to travel to countries ravaged by Zika virus, Brazil’s current situation worsens each day. Industry experts have expressed that travel advisories exist only for pregnant women, so tourism shouldn’t be impacted in the long run even with the 2016 Summer Olympics coming up soon. They did warn of long-term economic issues associated with Brazilians not having babies, stating how it would affect healthcare, education and other industries. Overall, experts are unable to predict just how much Zika will affect the economy.

In the photo: Carnaval do Brasil (Brazilian Carnival) attracts millions of tourists and others to celebrate the beginning of Catholic Lent. Some agencies had called to cancel this year’s festivities in light of the Zika epidemic. Photo Credit: Alexandre Moreira/ZUMA Wire

In the photo: Carnaval do Brasil (Brazilian Carnival) attracts millions of tourists and others to celebrate the beginning of Catholic Lent. Some agencies had called to cancel this year’s festivities in light of the Zika epidemic. Photo Credit: Alexandre Moreira/ZUMA Wire

Healthcare workers in the US have discovered 107 cases of Zika according to a report published by the CDC published Friday, February 26. They also found 40 cases in US territories (35 in Puerto Rico and four in American Samoa, and one in the US Virgin Islands). In the US, nine of those 107 cases were in pregnant women. One of those women already gave birth to a baby with severe microcephaly. Of the two women who showed the symptoms associated with Zika in their second trimester, one delivered a seemingly healthy baby and the other is still carrying her baby without complications. One pregnant woman exposed to the virus in her third trimester also delivered a seemingly healthy baby.

History of the Disease

The disease itself comes from the same viral family as yellow fever, West Nile, chikungunya, and dengue. According to reports, Zika was first discovered in 1947, when scientists discovered a monkey in Uganda with the virus. Since then, the virus has become endemic in much of Africa. The virus usually stays around the equator from Africa to Asia, and within the last nine years was found in island nations in the Pacific Ocean. In May of 2015, the disease made its debut in Brazil.

Doctors believe that the virus is becoming such a problem because the regions it is currently affecting have no built-in immunity to the disease itself. Because of this, microcephaly and Guillain-Barré disease are showing up at higher rates than they have in the past in these areas.

Originally, scientists regarded Zika as harmless, but in light of microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, opinions in the scientific community are slowly changing. Zika was regarded as pandemic to the Brazilian region by the National Institute of Health, but Brazilian Minister of Health Marcelo Castro recently declared Zika endemic to the area. According to Dr. Anne Schuchat of the CDC, more countries will be affected by this disease as time goes on.

Modes of Transmission

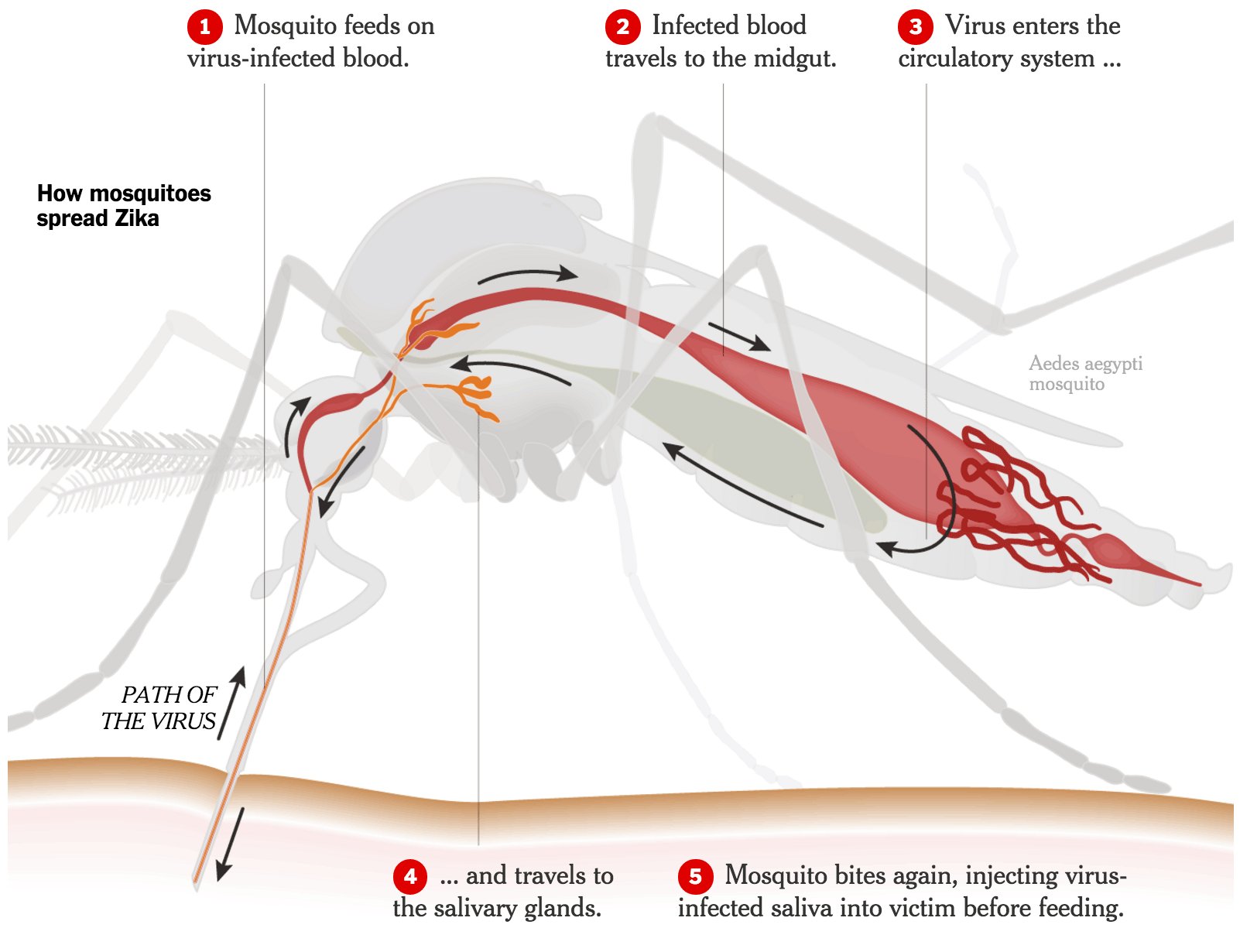

Zika is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, which require very small amounts of water to breed and usually feed in the daylight. Scientists are not sure how effective other species like the Ae. albopictus are at transmitting the virus. Both the Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito) and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have been linked to Zika transmission and are present throughout much of the US.

In the photo: The path of Zika virus as it travels through a mosquito. Photo Credit: Sarah Almukhtar and Mika Gröndahl (Sources: Dr. W. Augustine Dunn; Oxitec; The Anatomical Life of the Mosquito, R. E. Snodgrass)

Female Ae. aegypti mosquito is the principal culprit spreading Zika in Central and Latin America. By feeding mostly in the day, the Ae. aegypti mosquito changes up how most people expect to deal with mosquitoes in general. These mosquitoes are able to spread the virus faster as a result. Also, only 1 in 5 of people affected with Zika will actually develop outward-appearing symptoms, which include fever, pink eye, rashes, and joint pain. According to Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) epidemic alert and response chief, because there is no known immunity to Zika and the mosquito type that is instrumental in its spread is common throughout the Americas, Zika is able to spread much faster than is expected. The Ae. aegypti mosquito is different from other mosquitoes in its ability to reproduce in areas with very little water, such as a flower vase. All of these things help in making Ae. aegypti the prime vector or infection.

Pregnant women can get Zika through infection via mosquito bites or by her sex partner. They can then pass on the virus to their fetus during pregnancy or at term. The CDC also believes that once someone is infected with Zika, that person would most likely be protected by a future Zika infection.

Experts say to try to avoid contact with other mosquitoes for approximately 20 days. In terms of sexual transmission, the CDC has noted that there are no reports as of yet of infected women transmitting the virus to sexual partners. Though Zika has been discovered in breast milk of nursing mothers, the CDC is reluctant to say a baby can get the virus through those means. The CDC stated that they have seen an uptick in the amount of cases of women becoming infected through sex with an infected partner. While the CDC is unable to get specifics on how long human secretions like semen and vaginal fluids may contain the virus due to a lack of “policing” by the immune system in our reproductive organs, the CDC stressed the importance of practicing safe sex, especially in the case of pregnant women whose sex partners have traveled to areas affected by Zika. Doctors suggest remaining abstinent at least a month to ensure that one won’t pass on an asymptomatic infection. If abstinence is not an option, the CDC stressed the importance of using condoms and other forms of protection properly.

On the mosquito front, the main mode of transmission Ae. aegypti has been found in Washington, D.C., an area where this mosquito usually does not reside annually. Usually, the species invades areas where there is no prolonged cold weather. Researchers believe there may be two reasons for this recent spread: climate change and the mosquito’s ability to breed in man-made structures conducive to its breeding needs. It has been noted that all life stages for these mosquitoes require temperatures above freezing point. Measured from 2013-15, researchers found a consistent population in the area. Authorities have been quick to point out that they do not expect the amount of mosquitoes present in these unexpected areas to take over these cities. In other words, yes, the mosquitoes are in areas that the CDC did not expect them to be, but that does not mean we should break into a Zika-spurred panic.

In the photo: The Zika Outbreak as of March 22, 2016. Photo Credit: Healthmap.org

In the photo: The Zika Outbreak as of March 22, 2016. Photo Credit: Healthmap.org

Testing and Treatment

Currently no vaccine or treatments tailored to Zika exist, which is why much of the efforts to curb this issue rely on mosquito control. Many countries have advised their women not to get pregnant or at least plan no not getting pregnant anytime soon. The WHO believes that full-scale testing of a vaccine is at least 18 months away. This is due to the rigor and ethical dilemmas associated with creating a vaccine that is indeed safe for consumption.

In terms of the virus test, false positives from the screener can result if the infected person is infected with dengue fever, as both produce similar antibodies. False negatives can also occur as a person may not have enough viral proteins in his or her body since the person has nearly recovered from infection.

According to the CDC, the best thing people can do to protect themselves from Zika is not traveling to places affected by the disease. If someone is obligated to go to one of these areas, the CDC recommends he or she use EPA-approved repellent over sunscreen, sleep in rooms with air conditioning and screens, and wear clothes that cover the body, like long pants and long-sleeve shirts. Thick clothing is also recommended. They also suggest women of childbearing age discuss how to prevent unintended pregnancies through family planning and counseling. The CDC stressed the importance of proper contraceptive methods. It also suggested that local health officials implement routine testing of Zika for pregnant women.

In the infographic: The basics on Zika Virus and its symptoms. Infographic Credit: Pan-American Health Organization

In the infographic: The basics on Zika Virus and its symptoms. Infographic Credit: Pan-American Health Organization

Click here for Part 2, which details how the International community has responded, possible solutions, and how reproductive and women’s rights may end up on the chopping board.

_ _

Featured Image Credit: Felipe Dana/AP Images

Contributing Research:

Botelho, 2016; Cao-Lormeau, Blake, Mons, Lastère, Roche, Vanhomwegen, Dub, Baudouin, Teissier, Larre, Vial, Decam, Choumet, Halstead, Willison, Musset, Manuguerra, Despres, Fournier, Mallet, Musso, Fontanet, Neil, & Ghawché, 2016; Cauchemez, Besnard, Bompard, Dub, Guillemette-Artur, Eyrolle-Guignot, Salje, Kerkhove, Abadie, Garel, Fontanet, & Mallet, 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016b; Christensen, 2016; Cohen, 2016a; Cohen, 2016b; Fantz & Darlington, 2016; Garrett, 2016; Goldschmidt, 2016; Hills, Russell, Hennessey, Williams, Oster, Fischer, & Mead, 2016; Johns Hopkins Medicine; LaMotte, 2016; Lima, Lovin, Hickner, & Severson, 2015; Oliveira, Cortez-Escalante, Gonaçalves, De Oliveira, Carmo, Henriques, Coelho, & Franca, 2016; McNeil, Louis, & St, 2016; Petroff, 2016b.