Editor’s Note: Ukraine-born Yona Tukuser is an unusual artist with the courage to address the darkest themes of the human condition, themes that have been taboo for centuries, a taboo only broken in the 19th century with the Raft of the Medusa (1819) by Théodore Géricault, a famously radical painting in its time and today an icon of French romanticism.

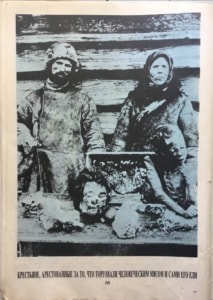

Now, with the war in Ukraine, we have Yona Tukuser’s inspired work – one of which was just bought by the Bulgarian state (represented by the Sofia City Art Gallery). An arresting and deeply emotional painting of the 1921 Povolzhye famine, it includes the black-and-white photograph of an episode of Russian cannibalism that inspired Yona’s project “Hunger”.

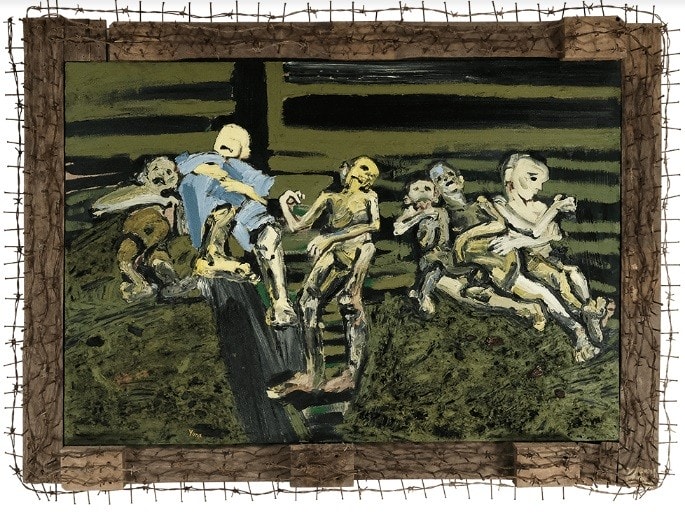

This project – which has been going on for 13 years – is Yona’s way to document the terrible famines that plagued Ukraine in the 20th century – the most famous one being the “Great Famine” of 1932-33, a.k.a the Holodomor, at the hands of Stalin, historically the first methodical genocide using food as a weapon that killed from 3.5 to 7 million (or more) people.

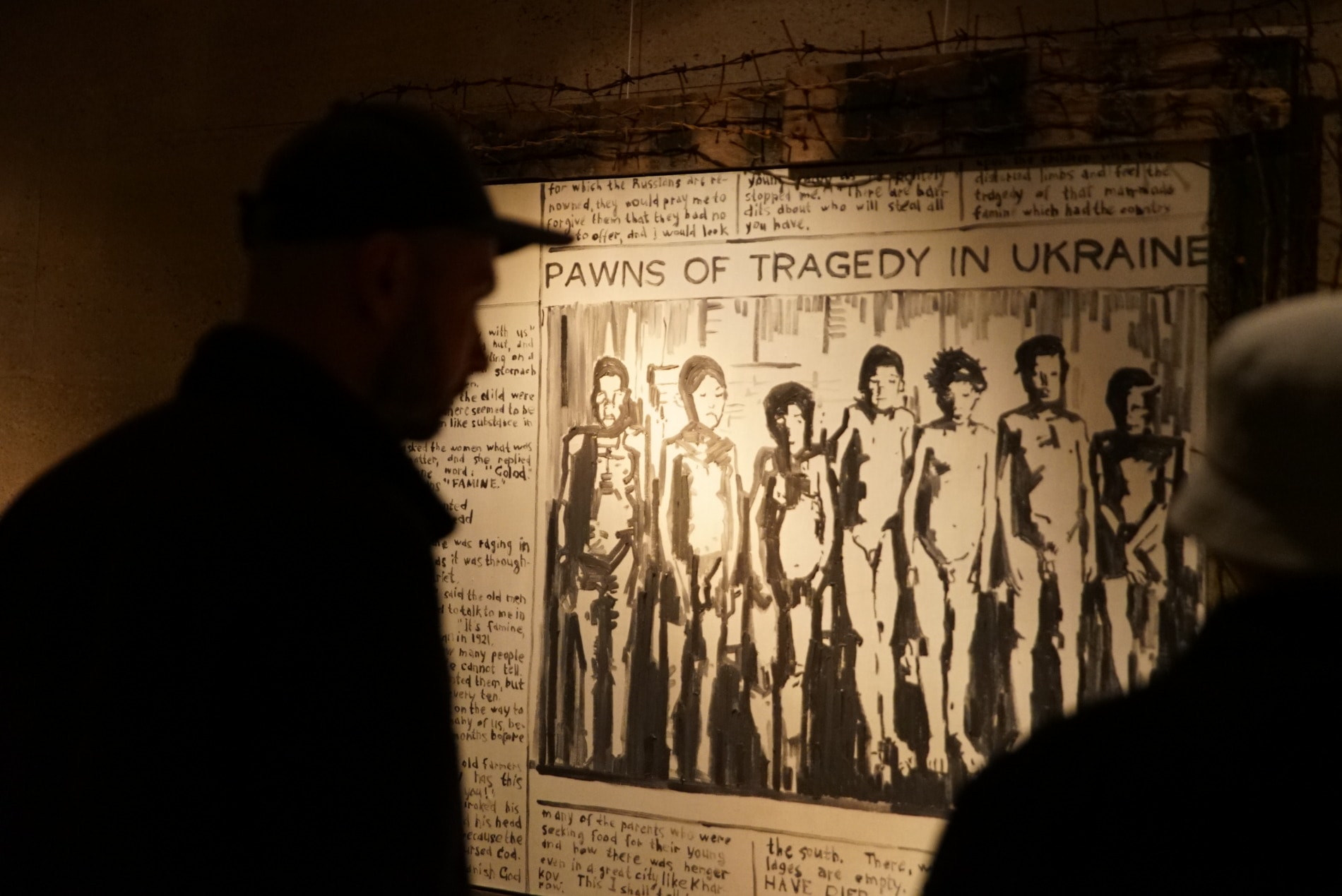

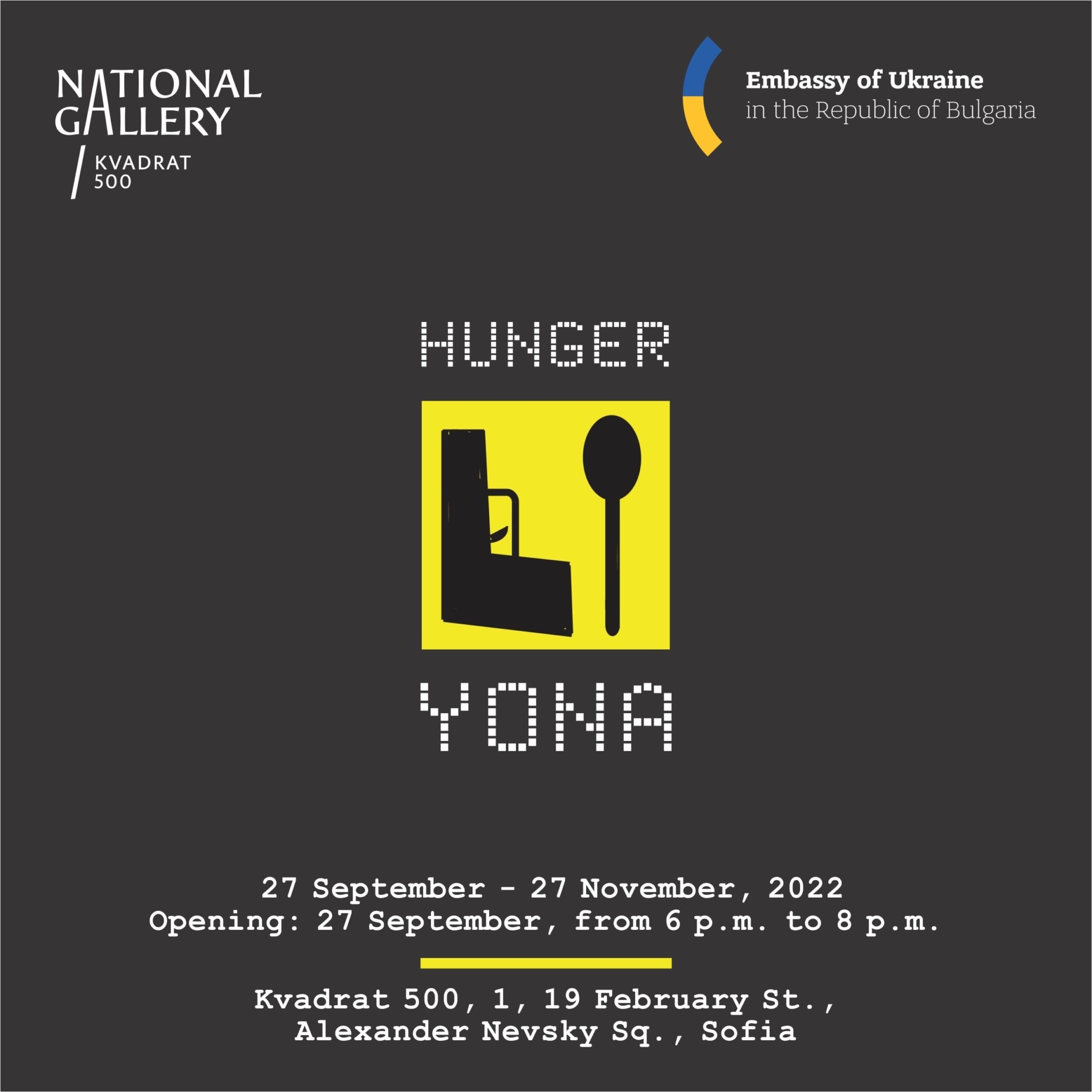

A gruesome black-and-white photograph gave root to young artist Yona Tukuser’s newest exhibition on display until November 27 at The National Gallery of Bulgaria “Kvadrat 500”, along with her entire multi-year project “Hunger”.

Yona Tukuser was born in 1986 to a Bulgarian family in the village of Glavan – 70 km away from the Danube Delta in Ukraine. But of all the events in her youth that shaped her career as an artist, it was that old photo of cannibals from Russia selling human meat (see below), which Yona’s 5th-grade History teacher showed her class, that inspired her to create the “Hunger” project.

Upon seeing the image, young Yona was shocked by the human cruelty portrayed in it. Her innocent mind did not believe it possible that one human being would sell another to be consumed.

Yona Tukuser’s artistic path: How she went from an old black-and-white photograph to her art today

Later in life, when school was over, Yona became a student at the National Academy of Art in Sofia and mastered the craft of painting, finally succeeding in pouring her impressions of mankind, hunger, and hunger’s consequences on canvas.

She compares herself to a mute who had, at last, gathered the strength to let out a terrified yell.

From this photograph of cannibalism she had seen long ago as a young girl, Yona drew inspiration for her dark painting bought by the State of Bulgaria. She made that photograph an integral part of the painting (in the left part of the painting, under the man’s face):

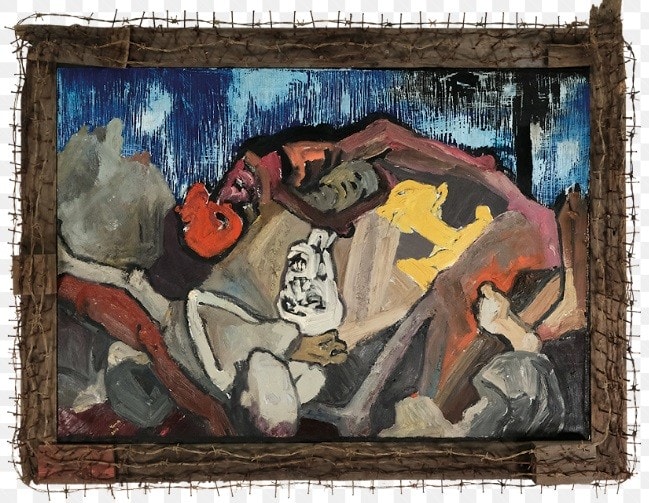

The young artist uses the style of metamodernism as her tool of expression and research. Metamodernism, born from a need to go beyond the post-modern, encompasses different, contradictory points of view on the same phenomena and processes.

As Yona explains, her exhibition, along with her entire project “Hunger”, is organized around the major 20th-century famines in Ukraine caused by wars and Soviet policies:

“The famine caused by these events is presented in my exhibition as three periods: the first is the famine of the 1920s, then the famous famine of the 1930s (this year marks the 90th anniversary of these tragic events, in which about 10 million people died, meanwhile also marking seventy-five years since the post-war famine of 1946-1947, in which the largest number of Bulgarians born in Ukraine died, a third of their total count or nearly a hundred thousand) In truth, precisely those who died were the disobedient, those who refused to submit to Soviet rule and practically died defending their freedom.”

The works presented and her project “Hunger” are the result of the artist’s 13 years of research into state archives documents from Izmail and Odesa, describing the main famines suffered in Ukraine in the 20th century, all three man-made famines: 1921-1922, 1932-1933, and 1946-47.

The exhibition consists of paintings created from 2010 onwards. Two of the paintings are from 2022, made after the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine. Not all canvases are shown in the exhibition, as a large part of them are still in Ukraine.

Yona plans to augment the final part of her project “Hunger” with another 20 monumental canvases dedicated to famine-caused cannibalism and based on filmed witness accounts, which she captured in 2018. She put those filmed accounts together in a video titled “Video-painting ‘ANTHROPOPHAGE’“:

This extraordinary “video-painting” was a result of the new direction Yona’s research took her. She had resorted to interviewing famine survivors to collect information:

“Provoked by missing information in official documents of the prosecutor’s office confirming the presence of cannibalism in Bessarabia in the period 1946-1947, I undertook research through an alternative source of historical information – oral history. I conducted conversations in front of a video camera with 86 people from twelve settlements for the period from 10th April to 21st May 2018. Turning to the living collective memory of local residents, I recorded shared memories of the existence of cannibalism in their villages.”

Her research led the young metamodernist to the following conclusion:

“Having collected so many stories about cases of cannibals, I was initially horrified by the cruelty of this crime – man turned into a primal, ferocious creature which lost its human form… but then I doubted: “Maybe the cannibals were not criminals, but victims?” To what state did a person have to be brought forcefully, what moral attitudes had to be broken in them in order for that human to begin consuming another human being? Was this an experiment conducted on that person – where is the line when a man ceases to be a man?”

Throughout the years of its development, Yona’s “Hunger” project was plagued by constant setbacks for the artist at every step of the way – both personal and political.

In 2010, two weeks before the opening of the exhibition, Yona’s father passed away, and “Hunger” was postponed until 2011. She told me that during 2013-14, while she was preparing a second attempt at her exhibition and placing the finishing touches on her paintings – this time in New York, in the United Nations Headquarters – the war in Ukraine broke out and Russia annexed Crimea.

Seeing footage of mothers and their children being shot down in cold blood during the conflict shocked Tukuser into abandoning her canvases, as she feared her artwork had become an omen of death and would cause disasters and massacres.

It was only last year that Yona gathered the courage to finalize her paintings and realize her exhibition as she overcame her fear of the “Hunger” project invoking death.

Yona then returned to her family home in Ukraine and prepared another eighty large empty canvases. On these, she would recreate witness accounts about the survival and consequences of famine and cannibalism during 1946-47 in the post-WWII Odessa region.

However, once more the artist was forced to flee her family home as a full-scale war in Ukraine engulfed the country.

Having finally negotiated the guaranteed opening of her exhibition in September of 2022 with the support of the Ukrainian Embassy in Sofia, Yona had her gallery banner unexpectedly taken off the main entrance of “Kvadrat 500” and placed in a poorly visible corner outside the main gates – not even a full month after the launch of “Hunger”.

It seems that the reason behind the banner’s removal was that Yona’s project displayed an uncomfortable historical truth which was perceived as a nuisance by some people in a position to have that banner moved.

But historical truth rings differently for most people who appreciate being told what the past really looked like, especially when it coincides with their experience of the recent past and current events.

The exhibition’s emotional impact on the public has been exceptionally strong, as men, women, schoolchildren, and the elderly alike were seen stepping out of the gallery hall in tears.

Some visitors went as far as describing how they were able to sense the smell of an animal carcass upon seeing a specific painting. Others approached and talked to the artist, asking her additional questions, expressing their admiration for her work, and warmly shaking her hand.

Yona believes it is her artistic purpose to awaken an emotional response from within the community and feels she has accomplished this.

In her quest to provoke thought and feelings in the public and give a voice to the voiceless victims of famine, Yona has truly succeeded in creating a work that stretches beyond the boundaries of art into the academic sphere and enriches it.

This year the artist plans to revisit her family home in Ukraine and continue painting new works. Yona is currently negotiating for her exhibition to be presented in various countries across Western Europe.

The young artist seeks to draw attention to the way in which human history repeats itself :

“In the first days of the war, the horrified elderly Bulgarians in Bessarabia, who survived the post-war famine, hurried to bury their flour, sugar and oil in the garden, scared that another famine was coming.”

“The “Hunger” project shows how the contemporary world has become hostage to the unpunished crimes of Soviet totalitarianism and, in particular, to the repressive, anti-peasant actions that contributed to the mass starvation of the population.

Philosopher George Santayana’s aphorism that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, should sound like an alarm; and that is precisely the alarm bell which “will be amplified by the historical paintings that are part of the project”, said Yona Tukuser.

Yona draws a parallel between the mechanisms of man-made famine and Moscow’s course of action in regard to the recent Black Sea grain deal involving The United Nations, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine. She quotes U.S. Secretary of State Anthony J. Blinken:

“In suspending this arrangement, Russia is again weaponizing food in the war it started, directly impacting low- and middle-income countries and global food prices, and exacerbating already dire humanitarian crises and food insecurity.”

The very logo of Yona’s exhibition reads “Hunger is a weapon of mass destruction”, as shown in this invitation card:

She points out that historically Moscow has had plenty of experience in using food as a weapon of forced submission and blackmail, and that her artwork holds evidence of this:

“The last two canvases in the exhibition “Hunger” were painted this year and one reflects very current events. It is based on a story I heard from a 6-year-old boy from the city of Mariupol. The boy’s name is Ilya, his parents were killed, and he spent 3 weeks in a bomb shelter without food. “I was so hungry that I ate my friend’s toy”, says the boy, which is what I called the painting. He has now been rescued and is in Kyiv, where soldiers have found him a foster family.”

Then she goes on, to explain:

“On the opposite wall is a 4-meter painting of a boy from my home village who in 1946 was seen by neighbors dragging a half-decomposed horse carcass from the dump, to eat it to survive starvation. His parents also starved to death. This is how history repeats itself after 75 years.”

As Yona said in an interview with the National Bulgarian Radio, “My greatest childhood fear was war. I believed it to be the greatest evil and that nothing in the world was worse.”

But then, she discovered there was something worse than war. As she explains it, “In 2018 while I was interviewing witnesses for my documentary “Anthropophage” I had asked one elderly woman “What’s more horrifying – hunger or war ?”

This was a special witness, someone with a long and arduous life experience, as Yona explains: “This lady had survived both WWII and the post-war Great famine – her judgement of both was most realistic. The answer this old woman gave me made my blood run cold: “Hunger is more horrifying than war.”

And Yona to conclude: “I was shocked that there could be anything worse than war. But there is something even scarier than hunger, and that is the lack of love.”

Yona Tukuser’s website: https://www.yonatukuser.art/

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Looking at this painting, Yeat’s famous phrase comes to mind: “A terrible beauty is born”. This is a detail of “A boy with a dead horse”, one of Yona Tukuser’s most recent paintings (2022) shown at her exhibition at the National Gallery of Bulgaria (September-November 2022) – oil on canvas 120 x 400 cm