The risk of future pandemics is very real, and this article will argue that, given the nature of the risk, which arises more often than not from animals, the role of veterinarian assistance is more important than ever.

The good news is that the relationship between human, animal, plant, and environmental health, “One Health,” is garnering heightened recognition, policy articulation, and increased funding commitments. This is happening on many levels: in the context of international deliberations, such as the Pandemic Treaty negotiations now in their final stretch; within multilateral institutions and engaged United Nations agencies, in particular the One Health Quadripartite collaborations with WHO, FAO, UNEP, and WOAH, as well as individual governments.

The bad news is that little concrete action has yet been taken — with some exceptions here and there, while we all await results from the Pandemic Treaty negotiations. A vote on the final text (revised March draft here) is expected during the World Health Assembly meeting in May 2024.

If these institutions are to implement a One Health strategy effectively, there will need to be many more veterinarians than now exist or are in the training pipeline. This is the case for various reasons, but assuredly what is well-studied and recognized is that 60-70% of infectious diseases are of animal origin (zoonotic disease), and going forward, such numbers and risks are likely to increase.

A 2013 study conducted by the U.S. National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine well put it this way:

“…demographic, economic, political, and environmental developments of the 21st century will profoundly change society and the services the veterinary profession must provide in order to remain relevant to the public. Responsibilities will increasingly involve global issues with greater emphasis focused on the interface of human, animal, and ecosystem health. To meet these needs, there are doubts that the present supply of veterinarians is adequate in biomedical research, industry, academia, companion animal practice, food animal medicine, public health, and wildlife health.”

This situation has not changed in the ensuing decade and worsened with expanding populations, and degradation of the environment.

The first line of prevention, detection, and response is awareness of what is found and can be controlled in animals. And those best placed are trained veterinarians.

Unfortunately, there are far too few, and constraints include (1) a limited number of veterinary schools, (2) high costs to attendees, and, in most cases, (3) much lower incomes once they go into practice, certainly in comparison to their medical school graduates.

A brief “veterinarian” history

The English word “veterinarian” comes from the Latin verb “to draw” (as in “pull”) and was first applied to those who cared for “any animal that works with a yoke” — cattle or horses. The term “veterinary medicine” is most commonly tied to the Roman physician Galen or the earlier Greek “Father of Medicine” Hippocrates.

The first veterinary school was established in Lyon, France, by Claude Bourgelat offering formal education in veterinary public health, bringing attention to the importance of animal health and its interaction with human health in Europe.

The current situation

There are about 600,000 veterinarians globally, and they are unevenly distributed. Fewest are found in the agricultural areas of developing countries, the most are working in urban settings in the developed world.

Furthermore, engagement has grown and increasingly animal health has expanded in the private sector, now a huge global industry that encompasses multiple elements.

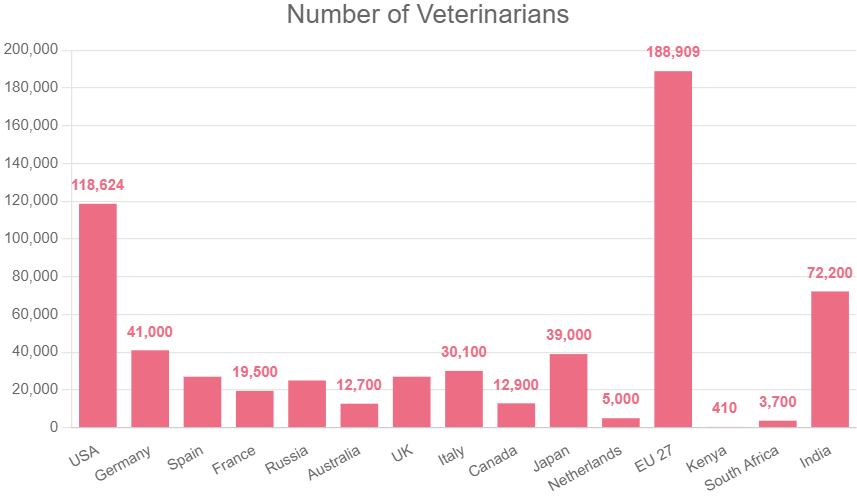

The range of medications and medical equipment, specialized services, and treatments has expanded dramatically in recent years (4). The figure below (5) shows the wide disparity in numbers of veterinarians globally, and hence access to veterinarians varies around the world. As pet populations rise, this puts immense pressure on the existing numbers of veterinarians providing care, with implications for burnout.

While advanced economies vary, they often have much in common. A recent report by the Federation of Veterinarians in Europe describes the profession this way:

“There are now an estimated 309,144 veterinarians in Europe, predominantly under the age of 45, and trending towards feminization. The vast majority (81%) of veterinarians work full-time, with employment most commonly in remains clinical practice (58%), and within this, predominantly small animal clinical practice.”

Taking into account needs, the veterinarian shortage is intensified with regard to large animals and rural practices. Typically, their pay is lower than that of their urban counterparts. They face demanding work schedules that are all too often less conducive to any harmonious or even just reasonable work/life balance.

In terms of the institutions that produce the veterinary workforce, there are roughly over 3,000 veterinary schools worldwide that graduate approximately 30,000 veterinarians annually. It is estimated that 5% of veterinarians retire each year.

The veterinary industry

Consider just one aspect of the animal health continuum, one that does not effectively cover the broad spectrum of related investments nor the entirety of agriculture or wildlife aspects: Animal hospitals and veterinary clinics that provide services such as consultation, surgery, care of animals suffering from disease or injury, and provide them with medicine, and other food items appropriate for animal nutrition.

Based on data in a recent report entitled “Veterinary Services Market: Growth Analysis and Anticipated Developments by 2032,” the global veterinary services market was valued at over $130 billion in 2022 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 5.64%, reaching over $181 billion by 2028.

One Health, veterinarians, and pandemic prevention

One Health positions the environmental sector and its ecosystem health as a core component of optimizing the health of animals and humans. Preventing future pandemics of animal origin will require preventing spillover from wildlife reservoirs into humans.

The current WHO draft Pandemic Treaty in its present form is limited. The draft primarily addresses secondary prevention — containing disease spread — rather than primary prevention, which focuses on spillover prevention and alteration in human behavioral factors that influence disease occurrence.

Human invasion of wildlife habitats for land has resulted in greatly heightened contact with wildlife reservoirs for disease, hunting for food, and illegal trade in wild animals for wet markets, mostly in Asia. Deforestation and industrialization impact animal habitats, and climate change affects rises in vector-borne diseases, emerging zoonoses, and threats to food security arising from antimicrobial resistance.

Related Articles: The Pandemic Agreement Draft: Will It Fully Embrace One Health? | One Health: A Paradigm Whose Time Has Come? | One Health Needs More Soft Power | The Concept of One Health Turns Global in 2021: How it was Born | One Health and Well-Being – Inspiring a Global Unity of Purpose | The One Health Story: It’s More Than Infectious Diseases

Primary prevention of transmission of zoonotic agents from animals to humans requires bringing veterinarians into the network of public health officers, physicians, and environmental health officers. The veterinarian is a necessary part of the public health team, identifying diseases in animals before they spill over into human populations.

The veterinarian is tasked with preventing disease in animals (vaccines, biosecurity) and does so by avoiding excessive use of antimicrobials. This helps prevent the development of antimicrobial resistance to diseases threatening human and animal health.

Additionally, veterinarians will be essential in conducting surveillance for the occurrence of zoonotic pathogens contributing to human disease and working alongside environmental health and public health to detect disease in animals before it impacts humans.

What might be done

Veterinary teaching is evolving, and some nontraditional models are now coming onstream. Interprofessional committees need to evaluate alternative models for veterinary education, particularly those that spread the cost of specialty training.

Further, there are innovations concerning access via the internet or artificial intelligence, which will increasingly make providing essential veterinary services more accessible and timelier.

Below are some recommendations drawn from the NAS study that remain applicable today.

- Engage professional veterinary organizations, academe, industry, and governments to identify actions needed to ensure the economic sustainability of veterinary schools and determine appropriate levels of compensation in comparison to other health professions;

- Offer specialty training by supporting interschool collaborations; relying on talent in private veterinary practices, specialty practices, industry, and public agencies; and enlisting the support of government, nongovernmental organizations, and other stakeholders;

- Reduce the length of pre-veterinary education to permit students with strong academic records to apply to veterinary school after one or two years of undergraduate study;

- Establish more joint degree programs, such as veterinary-public health masters or veterinary-business administration masters programs;

- Formulate new ways of delivering cost-effective services to rural environments, and enhance veterinary technician opportunities to extend animal health services to underserved areas.

- Encourage international entities, regions, and countries to recognize One Health as a priority, and within it, that relative to human health, with more attention and resources provided to address the animal element of the equation.

Veterinarians are critical for effective pandemic prevention, detection, and response. They are the One Health frontline professionals that international, regional, and national future efforts must recognize and support with policies, programs, educational and research institutions, and adequate resources to provide them with the wherewithal to do what we all need. Let’s hope they do so.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: A veterinarian vaccinating a cow against lumpy skin disease (LSD in Dewa village, assisted by FAO), March 1, 2023, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan. Cover Photo Credit: © FAO/Hashim Azizi.