The UN Food Systems Summit (UN FSS) convened along UNGA and held on Thursday this week, 23 September, ends in crisis, mired in political squabbles. Yet it had started well, two years ago, heralded as a landmark event using the UN as a “broker” to call on everyone around the world, the people and their leaders, to help solve mankind’s oldest problem – food to survive and thrive. A problem that had been made worse by the pandemic, with now some 3 billion people needing urgent help, according to FAO’s latest report, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021.

This was the promise:

Was the promise kept?

The UN Food Systems Summit version of the event: A success

If you go to the UN FSS website, the promise, they say, was amply fulfilled. It was the result of a huge effort worldwide, taking almost two years to prepare, an “18-month inclusive and engaging process with diverse stakeholders” across the world. The Food Systems Summit was preceded by two major preparatory events, one in the Philippines (termed “national food systems dialogues”), the other in Italy (a “pre-summit”), both held in July.

I watched some of the proceedings and I saw on the main stage dozens of world leaders explaining how well their country was doing in this area of food and sustainability and outlining all the ambitious goals they had decided to work for. In fact, at the end of the day, according to the UN press release, more than 150 countries had made “commitments” to “transform their food systems”, championing “greater participation and equity, especially amongst farmers, women, youth and indigenous group.”

The United States was singled out as one of the most notable “champions”, recalling that the Biden Administration, following the “code red” raised by the latest IPCC report on climate change, had announced a $10 billion pledge over five years to address climate change and help “feed the most vulnerable without exhausting natural resources” – noting however that (understandably) half of that sum would be spent domestically. Implicit here in the UN press release is the hope that some of it would go towards addressing global hunger and malnourishment.

One wonders however what is the relevance of this news since the U.S. never actually said how much of its money would go to food system transformation. But many ideas and ways to address the food issue were raised by other political leaders, including free school meals, advocated by Finnish President Sauli Niinistö who recalled that this had been done in Finland since the 1940s; “quality food for everyone” called for by the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina; the right to food evoked by Burkina Faso committing itself to include it in its constitution; sustainable consumption of green and blue foods to prevent biodiversity loss and addressing the accelerating crisis of non-communicable diseases among the priorities mentioned by Fiji, speaking on behalf of the Small Island Developing States.

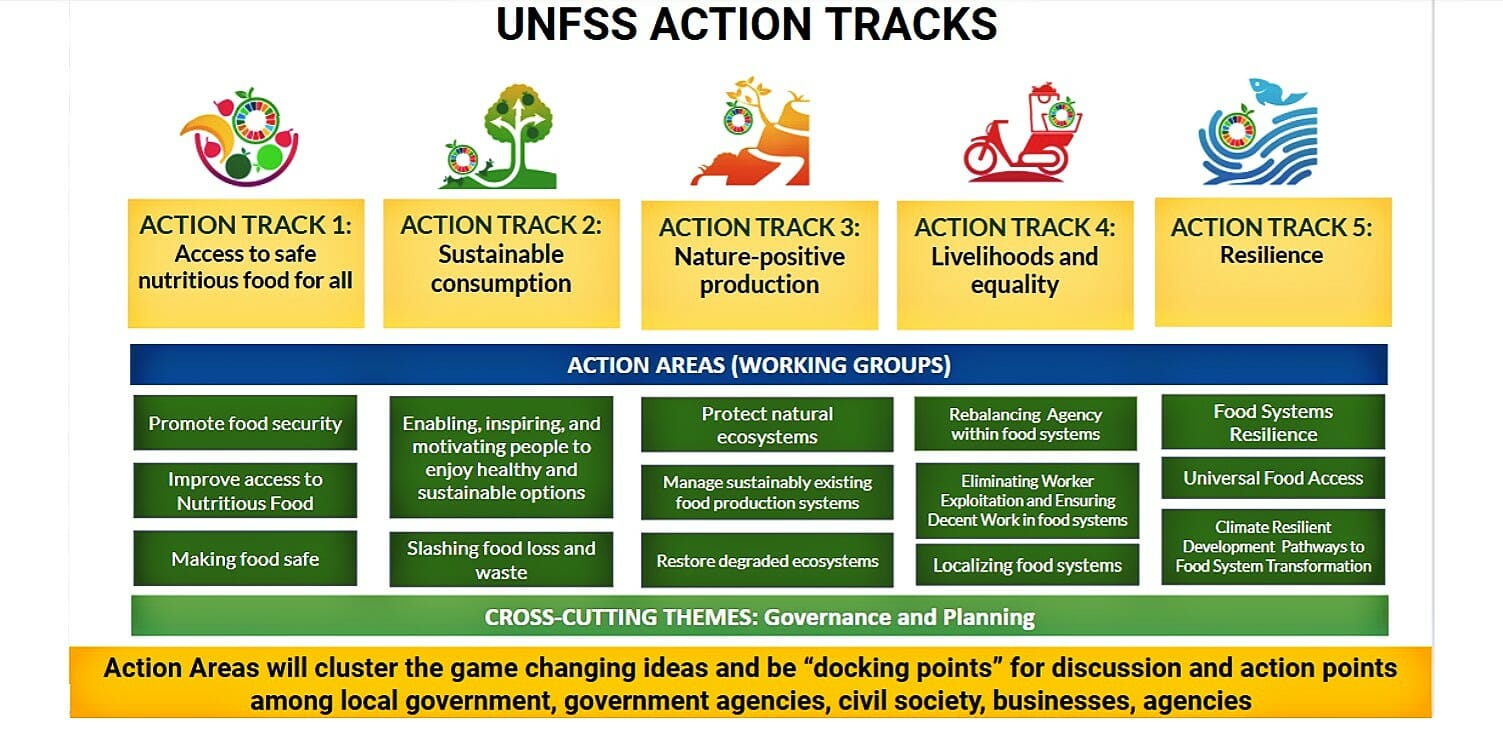

Of course, while these ideas (and others that came up) are all eminently laudable, none are new. There was no ground-breaking solution on offer. Nothing different from what FAO has been calling for over the past four decades, ever since FAO, the oldest UN technical agency focused on food and agriculture, started its first campaign to fight a hunger emergency caused by a devastating drought in the Sahel in the 1970s. Indeed, here, in a nutshell, is its latest call for action, setting out the way forward, for food system transformation:

The way forward for food system transformation. Source: The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021

Likewise, concern for local people was expressed by many leaders (though certainly not all the 90 world leaders that were said to attend UNGA in person). Among them, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who said New Zealand would join the Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems Coalition, because “For New Zealand, this means promoting the significant role of Māori in our food sectors and encouraging the growth of Māori agribusiness”; Honduras announced it would strengthen the role of local authorities; Samoa said it would promote traditional and indigenous knowledge to boost nature-positive production; Peru and the Philippines announced they supported formalization of land tenure.

Did this focus on local, indigenous people made the said people happy?

At a UN press briefing on Thursday, Myrna Cunningham, an Indigenous Peoples rights activist and Summit Advisory Committee member who launched the Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems, said “Indigenous Peoples have been supporting the Summit. We have organized dialogues in the seven socio-cultural regions, with almost 300 Indigenous Peoples organizations participating.” So far, 148 “commitments” have been “registered” and they are “collective or institutional commitments to action that are aligned to the Summit’s Action Areas.”

Many joined to make the point that the Summit was “very inclusive”. Elizabeth, Nsimadala, President of the Pan-African Farmers Organizations (PAFO) who represents 80 million farmers across 50 African countries said that. And the UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed concluded that “In terms of inclusiveness, I don’t know of a more inclusive process. People look at the SDGs. They see themselves in that, and we wanted to reflect that in this people solution Summit.”

The Global People’s Summit Version of the event: A failure – It was “anti-people”!

Unhappy with the UNFSS preparations, reportedly (according to their People’s Summit website), “thousands of rural peoples, people’s organizations, CSOs, and advocates” – actually 22 regional and international organizations, including the historic International Alliance of Women and the powerful Pesticide Action Network (PAN) – came together since the beginning of 2021 to organize, with the theme “Resist! End the global corporate food empire!”.

It was to be a three-day counter-summit to “expose and oppose the control of big corporations over food and agriculture” and pointedly, “the corporate capture of the UN, as exemplified by the key roles given to Bill Gates and other capitalist-controlled institutions in shaping the UN FSS agenda and outcomes”. Razan Zuayter, global co-chairperson of the People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty (PCFS) said the UN FSS “tried to repackage itself superficially as a ‘People’s Summit’ whilst a “true and legitimate People’s Summit should put the hungry and marginalized — landless farmers, agricultural workers, indigenous peoples, fisherfolk, rural women, youth, rural people living in occupied areas, and sanctioned peoples — at the helm of agenda-setting in the radical transformation of our food systems”.

For Sarojeni Rengam, PAN Asia Pacific executive director, with UN FSS, the “global corporate food empire” was out to “further consolidate their control of land, seeds, agricultural inputs, and markets by embedding themselves even deeper into policy-making processes of the UN.” The Pesticide Action Network of North America and Asia published a scathing post, calling the UN FSS a “toxic alliance”, recalling that each year, 385 million farmers and farm workers suffer from acute pesticide poisoning, that pesticides are a major driver of the “unprecedented collapse of insect populations and biodiversity loss” and that pesticides are petroleum-derived products directly contributing to climate change.

Meanwhile Pan International set up a petition to call on FAO to stop the #ToxicAlliance with CropLife. CropLife is the global trade association representing all of the largest agrochemical, pesticide, and seed companies.

What these people have set out to fight are the big transnational corporations such as Nestlé, Tyson and Bayer that dominate the market everywhere, starting in America and Europe where most of them come from. Making consumer choice an illusion.

The “People’s counter-mobilization to transform corporate food systems” kicked off with an 8-hour long global virtual rally and picked up with protests in front of FAO Headquarters in July during the UN FSS pre-summit.

Meanwhile, hunger persists even in the most advanced countries. In times of recession, about one-fifth of American families experience food insecurity. Food stamps and food banks play a big role to address the problem. For example, today, Feeding America is a network of 200 food banks providing food to about 600,000 pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and schools. It is the second-largest US charity, according to Forbes, with a revenue of $3.64bn in the last fiscal year. Yet food stamps and food banks are viewed by many as just putting a band-aid on American inequality and solving nothing.

The three-day counter-summit started on September 21 and ended on the day of the UN FSS with protest rallies in New York and a People’s Declaration for the radical transformation of the current food regimes. The declaration, signed by about 600 groups and individuals, states:

“[We] reject the ongoing corporate colonization of food systems and food governance under the facade of the United Nations Food Systems Summit … The struggle for sustainable, just and healthy food systems cannot be unhooked from the realities of the peoples whose rights, knowledge and livelihoods have gone unrecognized and disrespected.”

Most importantly, an analysis by Food Systems4People published on the eve of UN FSS highlighted the extent of the problem, saying that non-corporate participants had been sidelined in favor of “big corporations represented by and allied with business associations, non-profits and philanthropy groups” – including the Rockefeller Foundation, Gates Foundation and Stordalen Foundation and “corporate front groups and corporate-driven platforms such as the World Economic Forum (WEF)” and others.

The crux of the Food Systems4People accusation is this:

“The attempt to replace governance models of inclusive multilateralism, as established in the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS), with a multi-stakeholder model with supposedly equal responsibility of all, firstly weakens the role of the member states themselves; secondly facilitates an undue influence of corporate interests, a trend of corporate capture in the UN; and finally makes a clear definition of effective accountability systems impossible.”

What they are saying in effect, is that the CFS, as a tool to address global food issues, has stopped working.

What is the CFS and What is its role in the debacle of the UN FSS?

The CFS, or Committee on World Food Security, is one of the oldest fora in the UN system, established in 1975, and the first to open up to non-member states, i.e. allow civil society, both business and the general public to have a voice in its debates. It was reformed in 2009 to focus on hunger issues and participation was broadened “to ensure that voices of all relevant stakeholders were heard in the policy debate”.

And the idea for the UN FSS was born there, two years ago, with the realization that something urgently needed to be done if the 2030 SDGs were ever to be achieved.

Disclosure: I have attended many CFS annual meetings held at FAO Headquarters in Rome (first as staff and later as a delegate) and I have observed over the years how the so-called “private sector” representatives (big corporations and philanthropies with global reach) and the CSM – Civil Society Mechanism, composed of representatives from the whole spectrum of civil society, from NGOs and farmers associations to Indigenous People – vie for attention, always standing on opposite corners of the CFS meeting room, reflecting their divergent views.

Clearly, divergent views were heightened by the process of preparation for UN FSS and relations broke down following the annual CFS meeting last year (it always takes place in October): the CSM rebelled and decided to mount a counter-offensive.

Unexpected Support from UN Human Rights Office

The counter-mobilization against the UN FSS found unexpected support from another part of the UN system: The UN Human Rights Office of the Commissioner (OHCHR). On the eve of UN FSS, on September 22, three UN Human Rights experts, Mr. Michael Fakhri, Special Rapporteur on Right to Food, Dr. David Boyd, Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment and Mr. Olivier de Schutter, Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights” issued a joint statement and they plan to make a report to UNGA to provide “further guidance on how to assess the Summit through human rights framework.” Michael Fakhri, in particular, was very active in countering UN FSS, with an article in the UK Guardian pointing out that the UN FSS had taken “two years to plan”, yet “offered nothing to help feed families”.

From a Human Rights standpoint, the UN FSS failed to take into account the right to food. The Summit, the human rights experts said, “leaves victims of human rights violations no clear direction on how to overcome the inequality, violence, displacement, and environmental degradation caused by mainstream food systems.” In short, the agri-business responsible for the mess is allowed to walk away scot-free.

The solution? In two words: (1) Agro-ecology, one of the major policies long pushed by the FAO itself, based on farmers’ century-old knowledge of the land; and (2) food sovereignty, giving a voice to the people, recognizing their rights, including the right to food.

So what is needed, argue the three human rights experts, is a “human rights-based approach to food systems would hold corporations accountable. It would address ingrained power imbalances regarding access to land and water. And it would tackle core issues like land tenure, fair markets, and the privatization and monopolisation of seeds.”

And they vigorously push against the proposals “for a new science-policy interface to be established in the wake of the Food Systems Summit – either by extending the mandate of the Summit’s Scientific Group, or by establishing a permanent new panel or coordinating mechanism based on the Summit.” Instead, they urge continued reliance on the “widely recognized Committee on World Food Security (CFS) and its High-Level Panel of Experts guaranteeing a human rights approach and wide range of expertise.”

The upshot? Bring the whole issue back again to the CFS and adopt a strong Human Rights approach to ensure that the people’s voices are heard and that corporate power is appropriately curbed. The profit motive cannot continue to guide food systems – it does so at the expense of both human health and the survival of the planet. Stay tuned for further development in the UN’s alphabet soup of acronyms. Hopefully, one day, we will have results that go beyond mere words.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Image: 8 Indonesian activists arrested during People’s protests against UN FSS, September 23, 2021 Source: Hungry4Change press release