Historic was how one official described the May 2024 outcome of the UN Forum on Forests (UNFF) meeting, which repeated calls for urgent, accelerated action to halt and reverse deforestation.

Forestry management has long seemed an outlier compared to high-profile multilateral initiatives like the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and others. Yet to a large degree, the success of those hinges on tackling deforestation.

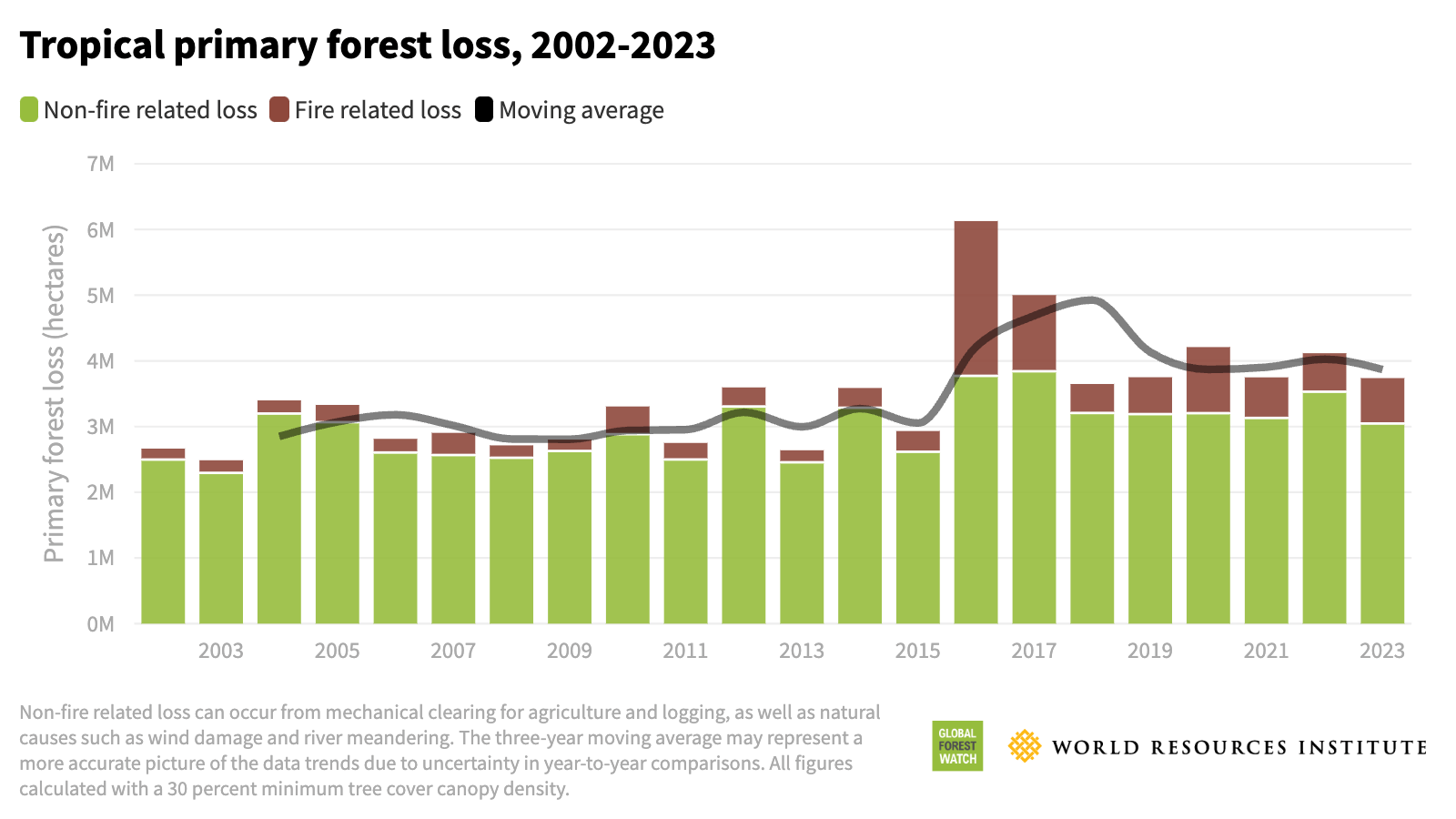

The challenge is daunting. The World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Forest Pulse estimates that 3.7 million hectares of tropical primary forests were lost in 2023. While Brazil and Colombia made substantial gains in forest protection, losses in Bolivia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), Nicaragua, and elsewhere mean tropical deforestation rates have remained largely unchanged. Threats are also increasingly affecting northern boreal forests. Last year’s Canadian wildfires consumed nearly 15 million hectares of forest, releasing 640 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), more than the annual emissions of Japan in 2022.

Heatwaves, wildfires, forest pests, and diseases are increasingly being attributed to climate change, bringing the forest-climate-biodiversity nexus and the Paris Agreement’s Article 5 objective of conserving and enhancing carbon sinks and reservoirs by tackling deforestation into sharper relief.

There are welcome signs that linking sustainable forestry management with climate change and efforts under the GBF are gaining traction. We briefly examine two – the changing composition of forestry finance and trade.

Financing

For three decades, financing has been the most contentious issue throughout the process that eventually led to the launching of the UNFF (from the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests, to the Intergovernmental Forum on Forests, the UNFF). Unable to agree on a global forest convention, and lacking a dedicated forest fund, UNFF member States were reduced to adopting a non-legally binding instrument, with supportive funding from outside agencies like the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and Green Climate Fund (GCF). Although forestry-earmarked development finance has inched upwards to around USD 2.2 billion a year, halting and reversing forestry loss is estimated to cost USD 460 billion annually.

The gap in forestry financing is among the widest of any global challenges. Governments are hoping to follow trends in climate finance by working with private markets via blended financing or stand-alone initiatives to narrow the gap.

Historically, the private sector has been at best cautious in how it approaches forestry projects. Commercial banking in many developing countries where most primary forests remain has been averse to providing loans to forestry projects, especially when they involve small and medium-sized producers who often lack financing guarantees, lending collateral, and clear land title. Moreover, lenders are often unaware of or indifferent to the needs of foresters who require long-term, patient capital to bridge limited short-term revenues and cashflow obstacles.

This is changing. Peru, for example, is negotiating cooperative deals with the domestic commercial banking sector with the aim of providing more favorable financing terms for forest producers, as well as establishing government-supported mechanisms for guaranteeing sustainable forest management (SFM) loans via a national forest fund. Dozens of blended forestry financing mechanisms have been launched in recent years. For example, in 2023, the Amazon Biodiversity Fund (ABF) was launched by the Brazilian Development Bank, Soros Economic Development Fund, L’Oréal Fund for Nature Regeneration, ASN Bank, and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), creating an investment fund to support smallholder farmers in conserving standing forests. Another is the joint Smithsonian Institute and the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) sustainable financing tool for the Paraguayan Chaco region to attract sustainable forestry investments.

Green bonds that prioritize forestry and sustainable agriculture are expanding. In 2022, the Paris branch of the Bank of China issued a USD 400 million biodiversity-themed three-year bond. Australia’s Nature Repair Market is up and running to attract private financing for ecosystem restoration, including through tradeable biodiversity credits. Other initiatives such as bio-credits are being tested in markets.

Expect more innovation in financing. In September 2024, Brazil launched initial plans for a USD 250 billion Tropical Forests Forever Fund, intended to bundle public and private financing to finance the protection of intact or standing forests. In October 2024, the missing piece of the ‘Paris Rulebook’ is near completion, with the final proposed rules for international carbon markets under Paris Agreement Article 6.4. If approved at the 2024 UN Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC COP 29), carbon removals through forests are expected to be its centerpiece.

Wider systemic efforts involve mainstreaming nature financing. In 2020, the Central Bank of the Netherlands examined the transmission channels through which biodiversity loss exposes firms to wider financial risks. Among the tools of the Task Force on Nature-Related Financial Disclosure (TNFD) is the ForestIQ to track risks linked to deforestation. After setting environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and climate risk disclosure standards, the International Sustainability Standards Board has begun work in nature and human capital financial reporting.

These and scores of other financing initiatives promise to slowly narrow the forestry financing gap. Practical indicators accessible to the public and useable by policymakers and the financial sector are needed. Initiatives such as that of Nature Positive’s State of Nature Metrics are especially welcome.

Global supply chains

While governments are increasingly turning to voluntary markets for sustainable forestry financing, the opposite is happening in tackling deforestation linked to global supply chains of soft commodities.

As much as 90% of all primary tropical forest losses are due to agricultural production for two main reasons. First, most tropical forest clearing is illegal, involving nomadic, slash-and-burn subsistence farming by the poor who clear lands to grow crops to feed their families and raise livestock.

The second reason, particularly in the case of the Amazon, involves the illegal cultivation of coca leaves to generate income. When nomadic farmers move on, the cleared land is taken over (often unlawfully) by landgrabbers to produce a high-value basket of exports including cattle, soy, or in the case of countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and others, palm oil and other soft commodities.

These commodities are big business. Estimates of the global market for palm oil alone was USD 68 billion in 2023.

Related Articles: 10 Major Companies Responsible for Deforestation | Amazon Deforestation Falls 66% in a Year: Is the Situation Finally Turning Around? | Just 7 Commodities Replaced an Area of Forest Twice the Size of Germany Between 2001 and 2015 | We Lost a Football Pitch of Primary Rainforest Every Six Seconds in 2019 | Can New EU Deforestation Law Help Curb Global Environmental Devastation?

Since the 1980s, there have been dozens of voluntary private sector initiatives aimed at delinking soft commodity exports from deforestation. High-profile examples include the Consumer Goods Forum zero deforestation 2020 pledge that was superseded by the Forest Positive platform, processes such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the Rimba Collective involving Southeast Asia palm oil, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, and similar initiatives. IISD’s State of Sustainability Initiatives helps track these on an ongoing basis.

Despite dozens of voluntary initiatives, deforestation linked to soft commodities remains among the leading causes of tropical forest loss. Accordingly, several jurisdictions have turned to blunter regulatory instruments linked to trade policy.

Norway was an early mover by committing in 2016 to zero deforestation imports. Other countries have followed suit, including France with its 2018 national deforestation-free strategy (SNDI), the US with its 2021 Forest Act disallowing imports tied to illegal deforestation, the UK with its 2021 Environment Act (para. 53), and others.

The most comprehensive mandatory approach comes from the EU. In June 2023, the EU introduced its EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), which calls for all imported cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya, and wood, as well as products derived from these commodities, to certify that they are delinked from deforestation. The EUDR will require importers to attest that their goods are deforestation-free, by reporting micro-level information such as the geolocation of farms where commodities were produced, the time of production, and other information. Acknowledging the complexity of reporting, attestation, and auditing requirements, in October 2024 the European Council postponed the EUDR timelines by one year, to the end of 2025. Acknowledging the complexity of reporting, attestation, and auditing requirements, in October 2024 the European Council postponed the EUDR timelines by one year, to the end of 2025.

The EUDR differs from the EU’s signature climate-linked trade measure known as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). However, like the CBAM, its compatibility with trade rules will likely be tested. Indonesia has questioned the measure at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Perhaps more interesting is whether blunter regulatory approaches that propose to restrict market access of soft commodities linked to deforestation may finally push voluntary initiatives to more stringent, transparent, and interoperable practices.

Looking ahead

More on-the-ground lessons are needed as to how increased market-led forestry financing will interact with proposed trade restrictions. To succeed, both need to address the primary causes of much deforestation led by poverty, illegal activities, and insecurity, particularly in remote forest locations.

To date, only a very small proportion of the numerous impoverished slash-and-burn subsistence farmers have been integrated into workforces engaged in successful forest concessions and community forest enterprises that are certified as sustainably managed. Expanding these initiatives will relieve pressure on existing intact forests and offer improved livelihoods and more reliable income opportunities to the people that most need them.

** **

This article was originally published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and is republished here as part of an editorial collaboration with the IISD. It was authored by Marti Colley, a journalist and administrator of LAGA consultants based in Panama; Jorge Illueca, former Managing Director and Assistant Executive Director of UNEP, senior official of UNFF, and President of LAGA; and Scott Vaughan, an IISD Senior Fellow.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: Casey Horner.