Most Americans are familiar with the past Administration’s Family Separation Policy. What gets lost in the flurry of Trump Administration misbehavior is the fact that child separation may be in a special category of its own.

Not only is it likely that the policy was in contravention to U.S. law, not only did the Administration continue the policy after it had been enjoined by the Courts to stop, but the Family Separation Policy is probably a human rights violation in the meaning of the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Since it’s clear in the domestic context, no one is likely to pay a price for this child abuse, it might be necessary to refer this case to the ICC. This situation is analogous to the role the Federal Government plays in enforcing civil rights violations in The States.

For example, the police officers involved in beating Rodney King were acquitted in a California court. Nonetheless, some of them were later convicted and jailed pursuant to prosecution by the Federal Government under Title 18 of the United States Code, which deals with the violation of Civil Rights.

…the targets of these child separation policies were the citizens of other countries, and those countries can bring complaints. Furthermore, such matters are relatively easy to investigate in the United States because of its policy on open records.

Local jurisdictions are often unwilling or unable to prosecute criminals in their midst so they must depend on the intervention of an outside authority. Thus, in the international context there is a need for institutions like the ICC and within the U.S. Federal system, laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Prior to 2002, the international prosecution of crimes against humanity was conducted on an ad hoc basis. For example, special tribunals were set up to prosecute offenders at the Nuremberg Trials and in association with the genocides in Rwanda and Kosovo.

In 1998 an international conference was convened in Rome to establish a permanent international criminal court. So far, 120 countries have signed on to what became the Rome Statute, including the United States. The Clinton Administration signed the Rome Statute (pending Ratification), but the Bush Administration reversed that decision and that has been the status of U.S. membership since.

According to the ICC’s documentation, it is not the purpose of the Court to supplant domestic law. In failed states or in those that flout international law, the Court may investigate, issue arrest warrants, try and even jail perpetrators of crimes as defined by the Rome agreement.

Even so, it becomes difficult for the ICC to do its work because the Court is not empowered to violate national sovereignty. Typically, the ICC can only prosecute a case when there has been a regime change in a target country.

Since the United States is neither a State Party to the Rome Statute, nor is likely to cooperate with an investigation, it will be particularly difficult to intervene in the case of family separation. Nevertheless, the targets of these child separation policies were the citizens of other countries, and those countries can bring complaints. Furthermore, such matters are relatively easy to investigate in the United States because of its policy on open records.

Related Articles: ICC vs Political Reality | Trump’s Anti-Immigration Policies

Family Separation

In March 2017, Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly, who later served as the White House Chief of Staff, told CNN news that the Trump Administration was considering a Family Separation Policy as part of its Zero Tolerance campaign against illegal immigration. The idea was that by taking children away from illegal immigrants, border crossing would be deterred.

The legal justification for this was U.S. law that allows the government to take away, for their own safety, the children of criminal parents. Since illegal entry into the United States is criminalized, child separation was considered appropriate.

Even though John Kelly made it clear in a 2017 interview that separating parents from their children was meant to be a deterrent, such a policy would most likely be regarded as a violation of U.S. Law. In addition, if illegal immigrants were treated as criminals, they were entitled to the due process rights of criminal defendants, none of which were available at the scale anticipated by the Zero Tolerance Policy.

On April 23, 2017, Kirstjen Nielsen, Kelly’s replacement at the Department of Homeland Security signed a memorandum explicitly authorizing the child separation policy. While the number of children separated from their guardians or parents has never been definitively established, the total is probably in excess of 4000 children.

In 2018, the Administration publicly ordered a halt to the Family Separation Policy, and Trump signed an Executive Order to that effect. Nevertheless, the Family Separation Policy continued, but without the previous cover of an official mandate.

Due to sloppy record-keeping by the Trump Administration, there are over 600 children still in U.S. custody whose parents cannot be found.

As word of the child separation policy and conditions under which the children were being held reached the press, outrage spurred the introduction of legislation in Congress, which failed, along with court cases intended to halt the practice. In June 2018, a Federal Judge ordered a suspension of the program and the return of all the children to their families within 30 days. Evidently, the Administration failed to comply.

The administration officials primarily involved in planning and implementing the Family Separation Policy were the aforementioned Kelly and Neilsen, Attorney General Jeff Sessions and his aide Gene Hamilton, Stephen Miller at the White House, and former President Trump as reported in the New York Times.

Being Called to Account

It is unlikely that any of these individuals will ever be called to account for their participation in this policy. After all, it remains questionable as to whether they even broke the law. However, simply to argue that they were “following orders,” is not an adequate defense in international law. After all, much of what the Nazis or Stalin did were official policy. At some point, individuals are obligated to refuse to carry out orders that are clearly inhumane.

Under the Rome Statute, the Family Separation Policy for the purpose of punishment is likely to be a “Crime Against Humanity” which the ICC defines as “Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law.”

Besides its tribunal, The ICC has an independent Office of Prosecutor. If that office were to investigate the family separation policy, it could do so on its own initiative or upon the referral of “states members” of the Rome Statute; the United States could make a referral (which I doubt it would do); or more likely, the country of a citizen whose child was taken away could make a referral.

Let’s be realistic, I don’t expect any member of the Trump Administration to be tried before the ICC. But it is not unreasonable to expect that if a former Trump official who furthered the family separation policy is under investigation by the ICC, he or she will be subject to detention for questioning, or possible arrest if that person travels to a country that is a state party to the Rome Statute.

This means losing their Paris, Rome, or Amsterdam privileges. Even transiting through those cities could subject them to detention — a statement that these sorts of policies are wrong and should be punished.

The recognition that crimes against humanity can be punished by the international community is a relatively recent phenomenon. The ICC is often cast in political terms, but the Court still serves an essential purpose.

For my friends on the right, consider this; For every investigation into Israeli occupation of the West Bank, if the U.S. were a party to the Rome Statute, there could be an investigation into the actions of the Venezuelan or Cuban Governments.

Shouldn’t the U.S. have an option besides armed intervention and country-wide sanctions to punish individual leaders in authoritarian states guilty of genocide or crimes against humanity? What the ICC does that we can’t do — is sanction individuals— and isn’t that essential in the pursuit of justice?

—

About the Author: Daniel P. Franklin is an Associate Professor Emeritus at Georgia State University. He is the author of seven books including Pitiful Giants: Presidents in their Final Term.

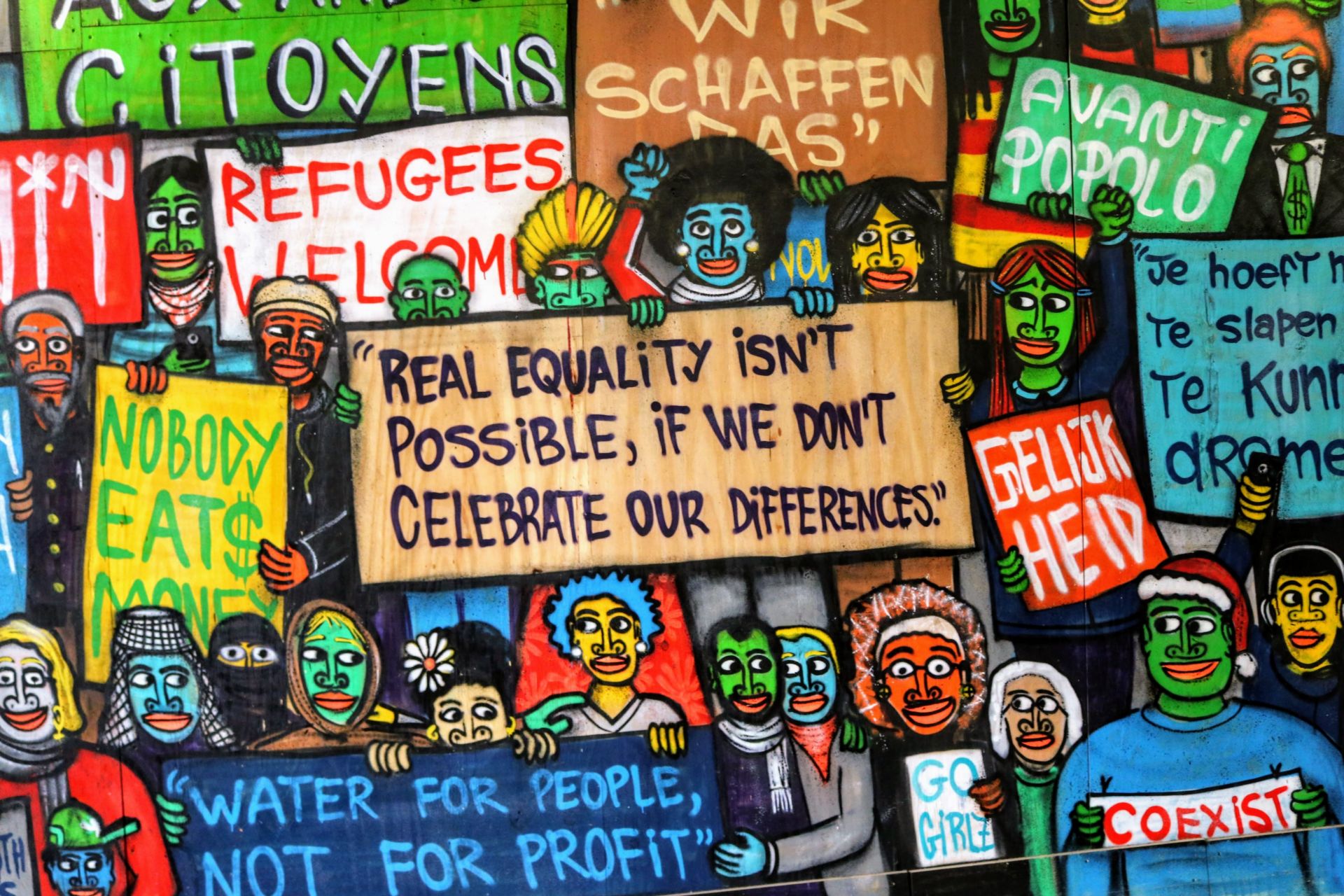

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Humanity Wall. — Featured Photo Credit: Unsplash.