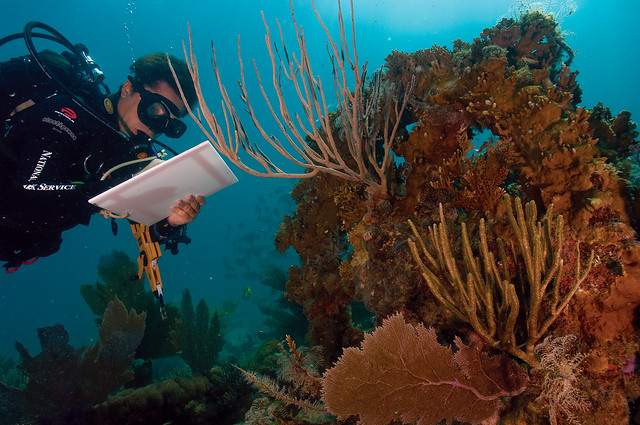

Before Prime minister Scott Morrison participated in the Pacific Islands Forum in the mid-August, it seemed likely to succeed among the Pacific countries. Morrison unveiled an US$337 million funding package for the Pacific region, in a move to curb climate change and to protect the ocean from rising sea levels and acidification, impeding organisms’ shell formation and causing coral deterioration.

But Australia’s relations with the southwestern corner of the Pacific are not just about the commitment of financial aid. Tuvalu, the hosted state of Pacific forum and one of the countries most at risk from climate change, is looking to Australia to do more. Australia is expected to shut down its coalmines, and to stop building new coal-fired power plants. However, during the negotiations of final communique, the Australian delegation worked hard to soften the language on climate change. They removed ‘crisis’ from the text as well as all references to coal and limiting warming to less than 1.5°C.

The disparaging comments that Morrison would allegedly have addressed to the Pacific leaders begs the question whether Australia looks forward to transitioning away from coal-powered economy. Of course, the effects of climate change are starting to make an impact on Australia’s environment and economy. Drought, floods, heat waves, bushfires, and storms have devastated crops, forests, and cities across the country and these all look set to become more frequent and intense.

Australia is the world’s top exporter of fossil fuels behind Russia and Saudi Arabia, and fifth biggest miner of fossil-related emissions. On the basis of current projections, the country could be responsible for up to 13% of the world’s carbon emissions by 2030. Fossil fuel industries are subsidised annually by about US$29 billion, or 2.3% of GDP. Liquified natural gas(LNG)is also a large and growing pollution problem, with Australia on track to become the world’s biggest LNG exporter, producing around a fifth of the world’s LNG. Ahead of these worrisome figures, protests arise and public opinion is stepping up pressure on federal and state governments to call for a more incisive action against climate change.

A Divisive Topic

Sir David Attenborough, British natural historian, has taken aim at ‘powerful figures’ in Australia who still do not believein climate change. Many conservative politicians and commentators accuse environmentalists of exaggerating problems. Amongst them, the former Prime minister of Australia, John Howard (1996-2007), reprimanded so called “climate change zealots,” claiming the Australian economy owes the mining sector an enormous debt since the export of coal, iron ore, oil, and gas helped Australia avoid the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

Pauline Hanson, Senator and leader of the right-wing movement OneNation, suggested scientists’ theories on climate change are disputed and have not been peer-reviewed yet. She claims that if climate change is occurring, it is not because of humans.

Whereas Ms Hanson and other conservative personalities refuse to admit that humanity is responsible for climate change, independent candidates at the Australian federal Parliament sought victory by discussing environmental protection issues during the last federal election campaign. Zali Steggall, former skiing Olympic athlete who won the federal seat of Warringah (NSW) against the former Prime minister Tony Abbott (2013-2015) last May, suggested that Australia – a ‘energy nation, not a coal nation’ – could take advantage of its abundant renewable energy resources, such as the highest solar radiation per square metre of any continent, rich wind, tidal resources, and existing hydro stations in the Snowy Mountains and Tasmania.

Helen Hindi, another independent member representing the federal district of Indi (Victoria) vowed to tackle the climate change crisis whose impact particularly affects regional Australia, as well as the physical and mental health of all Australian people.

Environmental movements, like the Greens, declare that Australia must reach net zero or net negative greenhouse gas emissions by no later than 2040. But in the election campaign, neither Liberals nor Labors — the two main political parties — were explicit about reducing Australia’s dependence on coal.

Impact on Society

According to the Climate Change Research Centre of the University of New South Wales, climate change presents different risks at a multilateral level to physical health, agriculture, and indigenous communities.

Experts argue climate change constitutesfirstlya health problem. All consequences related to global warming could cause increases in heat-related illness, particularly among the elderly and people with chronic conditions. Furthermore, extreme weather events can cause respiratory problems and physical distress. Scientists expect extremely hot episodes to have the greatest impact on mortality both in the hotter north and in cooler south of Australia (where there is likely to be an offsetting reduction in the number of cold-season deaths). Angus Taylor, Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction, said pollution went “up and down” but he acknowledged emissions had risen because of the booming of LNG.

Climate change has significant effects on agriculture. It damages crops, causes wool productivity to plummet in marginal areas, and makes the prices of farm products (above all, those of dairy industry) rise. In the wine sector, higher temperatures than usual — reaching up to 47°C — have had a dangerous impact on quality of grapes. Producers are adopting new cultivation techniques to ensure the future of their sector.

Sever water shortage is another concern. However, recent research shows that if global greenhouse gas mitigation efforts successfully limit the increase in temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate prescribes, the risk of severe water supply shortage in overpopulated cities like Melbourne might be considerably reduced.

Building new coalmines risks destroying the ancestral lands and cultures of Indigenous communities without their consent.

Building new coalmines risks destroying the ancestral lands and cultures of Indigenous communities without their consent. The exposure of Indigenous Australians to negative climate impacts on ecological landscape could reverberate on socio-economiclife.

The Tricky Path Towards an Effective Environmental Approach

According to the Department of Environment and Energy’s latest report, annual emissions for the year to December 2017 represents a 1.5 per cent increase in emissions, compared with the previous year. Australia emitted 534 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent in 2017-2018. The increase comes from the stationary energy (excluding electricity), transport, fugitive emissions, industrial processes and product use, waste and agriculture sectors. These increases were partially offset by a decline in emissions from the electricity sector.

De-carbonisation of the economy has become imperative as a disruptive task for political parties since 2007. Labor governments, led by Kevin Rudd (2007-10 and 2013), strived to usher in a national mechanism to curb greenhouse gas emissions, but failed twice to convince senators — and the Labor party itself — to approve it. Such a resounding defeat triggered an internal crisis within Labor. The former deputy of Mr Rudd, Julie Gillard (2010-2013), introduced a carbon tax to control the emissions.

Three years later, in 2014, Tony Abbott’s government (2013-15) repealed the scheme and established the Emission Reduction Fund (ERF), a voluntary mechanism which supports businesses, farmers, and land managers in taking practical action to reduce greenhouse gases above historical levels, respecting the Kyoto Protocol’s environmental targets. But it was not enough to bring down power prices. When Malcolm Turnbull (2105-18), Abbott’s successor as leader of Liberals, attempted to fix an obligation to cut emissions and increase renewable energy generation, its National Energy Guarantee provoked fierce opposition from within the National Coalition and was set aside.

Keeping the structure of the ERF, on February 2019, the Australian Government established a‘Climate Solutions Fund’to provide around US$1.3 billion, in a bid to reach Australia’s carbon emissions reduction target by 2030. Under this mechanism, the government purchases greenhouse gas abatement, quantified by Carbon Credit Units, through an auction process managed by the Clean Energy Regulator. Businesses, local councils, state governments, land managers and others are entitled to earn Australian carbon credits. The ERF has also included a safeguard mechanism,encouraging large businesses to cut down their emissions.

Under the Paris Agreement, Australia voluntarily agreed to reduce its cumulative emissions to 26-28% by 2030, below 2005 levels. But, if companies are allowed to use the Kyoto-era carry-over credits – that is, certificates that represent emissions Australia can release into the atmosphere – for the United Nation-sponsored agreement, only a 15% reduction is necessary to successfully meet its commitment. The carry-over does not break international law, but Australia’s decision to count the previous surplus units towards new targets has been condemned. As a result, Pacific leaders have called on Australia to abandon plans to use carry-over credits, as prescribed by the Nadi Bay Declaration.

Major Concerns of States and Territories

State and territory governments set to adhere to the national environmental targets by deploying new projects for renewable energy. People from urban and rural areas are experiencing the worst weather events in history and hope that Australia will begin investing more in the green energy sector to counter natural disasters.

In New South Wales, more than 99% of territory is currently drought-affected. The 31 months from January 2017 to July 2019 were the driest on record averaged over the Murray-Darling Basin.

Victoria, the state in Australia that is most affected by bushfires, passed the Climate Change Bill in 2017, fixing a long-term emissions reduction target of net zero by 2050.

South Australia, the state with the highest volumes of electricity at both the grid level and in total, experienced between September 28 and October 5,2016 a total blackout due to multiple tornadoes and severe thunderstorms causing significant damage to more than 20 transmission towers.

Over the past 15 years, Western Australia was prone to erosion events, associated with intense summer storms across the south-west areas.

In Hobart, the capital of Tasmania, average annual rainfall has declined since the mid-1970s.

In the tropical north of Australia, Aboriginal communities are faced with the negative impacts of climate change along with existing socio-economic disadvantages. Which include inadequate health and educational services, insufficient infrastructure, and limited employment opportunities.

Political Debate on the Adani Mine

Given its current exposure to extreme weather, Queensland should be on the frontline of climate change. Despite half a century of drought, it has been much slower than any other state or territory in the Commonwealth to shift towards renewable energy. Coal-fired power plants still provide more than 60% of grid electricity in the state, with 8.8 % of the state’s power coming from renewable sources in 2018.

In recent months, increasing apprehension about state government’s ability to cope with environmental issues has coincided with a series of large-scale protests against the Carmichael coal mine. Adani Group, an Indian conglomerate, will build the mine, the site of which is located in the North Galilee Basin. According to the StopAdani Movement, it would increase carbon pollution by about a billion tonnes over 60 years (the mine’s expected operating life), and allow more than 500 coal ships to travel through the 2,300km-long Great Barrier Reef each year. The latest outlook report by Marine Park Authority indicates the reef is in very poor condition. The mine would also have free access to 270 billion litres of Queensland’s groundwater, damaging the surrounding aquifers. However, aside from environmental movements, many people in Central Queensland consider Carmichael as an opportunity to boost the local economy.

According to Report No. 26, issued by the Development, Natural Resources and Agricultural Industry Development Committee of Queensland Parliament, the Galilee Basin is the world’s largest untouched thermal coal basin. The basin has a new coal export capacity of almost 300 million tonnes per year. It is thought that Carmichael mine contains ten billion tonnes of thermal coal resources.

On June 13, the Department of Environment and Science of Queensland government approved Adani’s Groundwater Dependent Ecosystem Management Plan (GDEMP), submitted with the department’s feedback and providing the maximum environmental protection for the area. This means Adani can now pour a total of US$3.3 billion into constructing roads and railways, potable water treatment, and sewage treatment plants. Either way, Adani still needs two more federal approvals and a few other arrangements before beginning to extract coal.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Australia: Empowering Indigenous Population”

“Stop Adani: how a grassroots environmental movement is ticking SDG boxes in Australia”

For the 2018-19 fiscal year, to date, the Queensland resources industry contributed US$3.37 billion (AUS$5 billion) in royalties. The Queensland Treasury considers the information available on both the value of the coal and the timing insufficient to prepare a reliable estimate of the royalties stemming from the Carmichael site annually. However, the treasury allegedly assumed 50 million tonnes produced every year, which equates to an annual royalty revenue at today’s prices of about US$337 billion per year.

Carmichael mining paves the way for at least eight more coal mines in the country. While twelve coal-fired power stations closed between 2012 and 2017, and the Liddell coal-fired plant is expected to turn off in 2023, the federal government is scheduled to approve gas expansion and fracking in Northern Territory and Western Australia.

Beyond the Environmental Risk

We should consider climate change not only as a risk to our existence but also a national security threat. In a private speech in June, General Campbell reportedly sounded a clear warning that climate change and Australia’s national security are inextricably intertwined. The 2016 Defence White Paper made it clear that natural disasters are a new and emerging menace, but the report only refers to Australia’s response to disaster relief in the South Pacific. The document downplays the impact of global warming and sea-level rise on the geostrategic objectives of the country. As the recent Pacific Forum showed, the row with South-West Pacific countries risks diminishing Australia’s influence on an area of key strategic importance.

The longer Australia delays decisive action, the more its economy will suffer. The Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia suggested that climate change poses a threat to Australian financial stability and has indirect implications for macroeconomic policy. Droughts in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s each subtracted about 1% from national GDP growth in the years they occurred. Worse still, the costs of adapting infrastructure to climate change can be even higher. Insurance companies clearly stated that in the absence of adaptation, premiums will inevitably rise.

Nevertheless, is it possible for the clean energy transition without the loss of a certain number of jobs? Adani Australia says that Carmichael mine requires 1,500-2,000 workers and is planned to create 6,750 indirect jobs in the region. Michelle Landry, Liberal member for Capricornia, claimed the mining and resources sector deliver the highest paying jobs to Central Queenslanders and contribute less than 40% of Gross Regional Product. Once Carmichael mining shuts down, rural communities of the Australian outback might be imperiled.

The Australian Academy of Science reported the country will have to adapt to the worst-case scenario if emissions of greenhouse gases are not curtailed to near zero in the future. The Coalition government is said to do its utmost to take real action, but abandoning its high-carbon economy does not appear to be, for now, the centerpiece of its political agenda.