Russia’s resurgent presence and strengthened role in the Balkan region has been the focus of increased attention and renewed interest in recent years. Highly catchy press titles such as “The Western Balkans are a testing ground in a new Cold War,” “The Western Balkans as a chessboard for superpower relations,” “Putin’s Game of Thrones in the Balkans,” and “Do the Western Balkans face a coming Russian storm?” highlight the narrative that, at the moment, the Western Balkans may indeed be a region where crucial geopolitical tensions and high stakes are playing out.[1]

The stimulus for this renewed interest is the perceptible shift in the balance of power in the Balkan region. While the European Union (EU) was looking inwards and focusing on its serious domestic challenges including the economic crisis in Greece and the eurozone, Brexit, the refugee/ migration crisis and the rise of eurosceptism and populist extremism in Europe, the geopolitical environment in the Balkan region was slowly but consistently shifting.

Related Topics: Democracy in Poland – Russian Misinformation Campaign – Euro Elections 2019

Perhaps the most crucial indication of this geopolitical shift has been the resurgence of Russian policy, influence and involvement in the region. Clearly, the slowdown of EU enlargement to the Western Balkans which was a side-effect of the EU prioritising domestic challenges, and the subsequent disillusionment and disenchantment of these countries concerning their European prospects, has created a new dynamic in the region that Russia has been keen to exploit.

Russia’s Strong Arm

Russia has invested considerable effort and resources in recent years in the Balkans in an attempt to strengthen its influence in the area. It has been successful on many fronts, and Russia’s economic, diplomatic and political influence in the region is greater than it has been at any point since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Moscow’s objectives are not only to prevent further expansion of the European Union and NATO into the Western Balkans, but to ultimately redress the balance of power and geopolitical landscape in what has traditionally been an area of intense Russian strategic importance. In this context, Russia’s most important instruments of influence in the region include energy policy, investment and “soft power” tools such as cultural, media and religious campaigns.

Concerning energy policy, Russia draws its strength from its role as a major supplier of energy and a key investor in the energy sector. Russia is by far the dominant oil and gas supplier in the Balkans, where all countries remain heavily dependent on imports to meet their needs. Russia’s energy influence is biggest in Serbia, North Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where it supplies almost 90% of natural gas needs.

Russian state-owned companies, such as Gazprom or Zarubezhneft, as well as private companies led by oligarchs close to the Kremlin, have led the way in recent years, benefitting from the hasty privatisation of businesses in the region and loose institutional governance. Russian firms have thus acquired a significant stake in the energy sectors of several Balkan countries, particularly Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina (specifically in Republika Srpska). Other major investors in the region are Lukoil, Itera, Yukos and Rosneft, as well as RusAl, Norilsk Nickel, Severstal and Meche (companies involved in ferrous and non-ferrous metals).

As far as investment in other sectors is concerned, with Greece (a major investor in the region until 2009) in crisis, and with European FDI (foreign direct investment) in the region declining, the Balkan countries are more open to offers of investment and financial support from other countries, such as China and Russia.

By 2015, Russia had become Montenegro’s largest investor, where about 32 percent of enterprises were under Russian ownership. Russian investment has been particularly evident in the sectors of real estate, tourism and leisure (in 2016, one third of all tourists in Montenegro came from Russia), but also in the sectors of food and drink, banking, agriculture and transport. Russian investment has also been very dynamic in recent years in Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina (mostly in Republika Srpska).

In addition to its strengthening economic presence, “soft power” tools have also given Russia considerable traction in the region. Russia has been rekindling traditional ties with many Balkan countries based on shared religious, historical and cultural affinities. The Christian Orthodox countries of Serbia and Montenegro, as well as Republika Srpska (within Bosnia-Herzegovina) are natural allies of Russia.

Photo Credit: Associated Press

Russia’s historical role resonates with many elites and with citizens who believe deeply in Russia as the protector of Orthodoxy and all Slavic peoples. Russia’s severe criticism of NATO’s bombing of Serbia in 1999, its decision to not recognise Kosovo’s declaration of independence from Serbia in 2008, as well as the use of its status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council in Serbia’s favour (by vetoing two UNSC resolutions condemning violence by Bosnian Serbs) are all central aspects of Russia’s powerful pro-Serb, pro-Slav narrative.

Finally, propaganda and misinformation have played a key part in Russia’s campaign to strengthen its position in the Western Balkans over the past years. Russian propaganda has exploited, fueled and capitalised upon the growing disillusionment of the EU on the European continent resulting from the slowdown of the EU’s enlargement process. Moscow’s strategy relies on a broad spectrum of instruments including media influence, public support for eurosceptic organisations and leaders, as well as the establishment of various high profile and active NGOs and civic associations.

In November 2014, the Kremlin’s news agency Russia Today began broadcasting a Serbian-language programme, Sputnik Srbija, out of Belgrade. Sputnik Srbija focuses inter alia on promoting narratives such as the EU and the USA as imperialist powers seeking to destroy Serbian identity and autonomy, the threat of a “Greater Albania” (that would result from the unification of ethnic Albanians currently living in Kosovo, North Macedonia and Albania) and the devastating NATO bombing campaign in Serbia in 1999. The aim has been to ultimately present Russia as Serbia’s natural ally and as the only great power that truly cares about injustice towards the Serb people.

Photo Credit: Associated Press

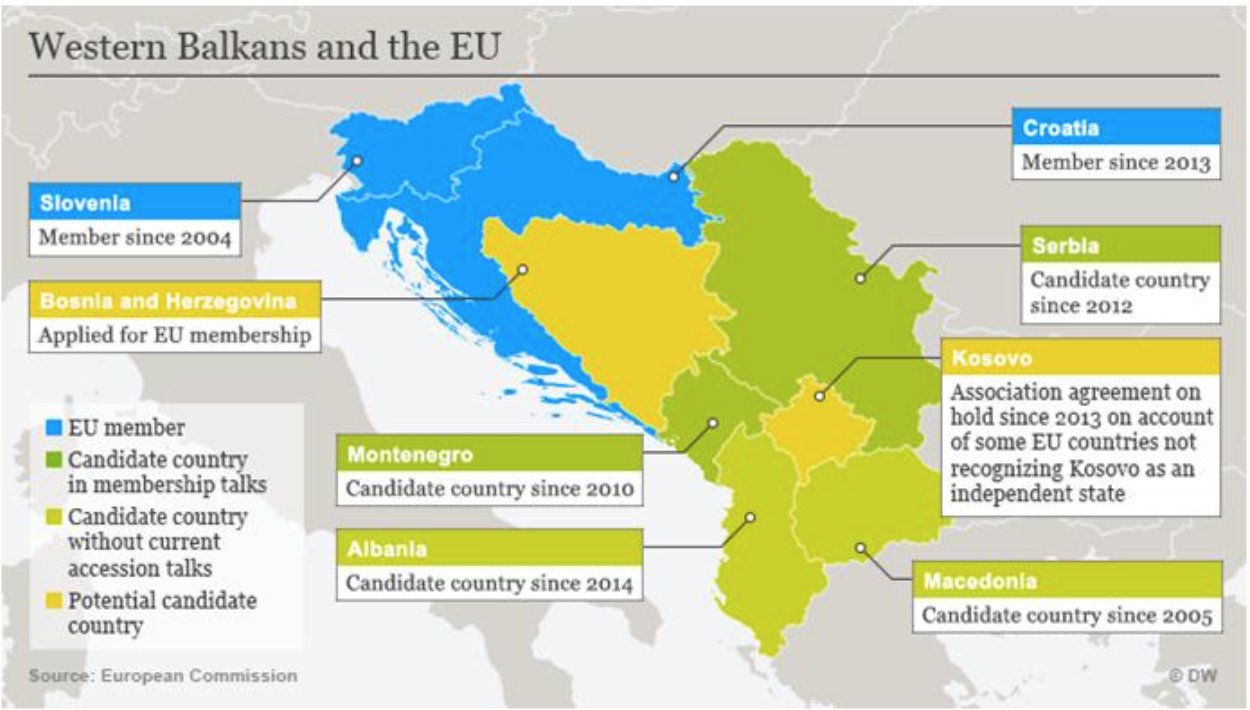

The EU’s Real Muscle

Ever since the Thessaloniki Summit of 2003 in which the European Union expressed its “unequivocal support for the European perspective of the Western Balkan countries” and declared that “the future of the Balkans is within the European Union,” the countries of the region have been on track to integrate into and work closer with European structures. Despite the endogenous and exogenous difficulties that are evident and have caused a slowdown in the EU enlargement process, the target and goals ultimately remain the same- full membership of Western Balkan states in the European Union.

The EU represents an overwhelmingly important economic partner for the Western Balkan countries. It is a vital strategic trading partner, a major source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), financial and developmental assistance, and is an important destination for migrant workers from the region (and, consequently, a source of remittances). These close economic relations have been boosted by the Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAA) between the EU and individual Western Balkan countries, which also include provisions for a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area.

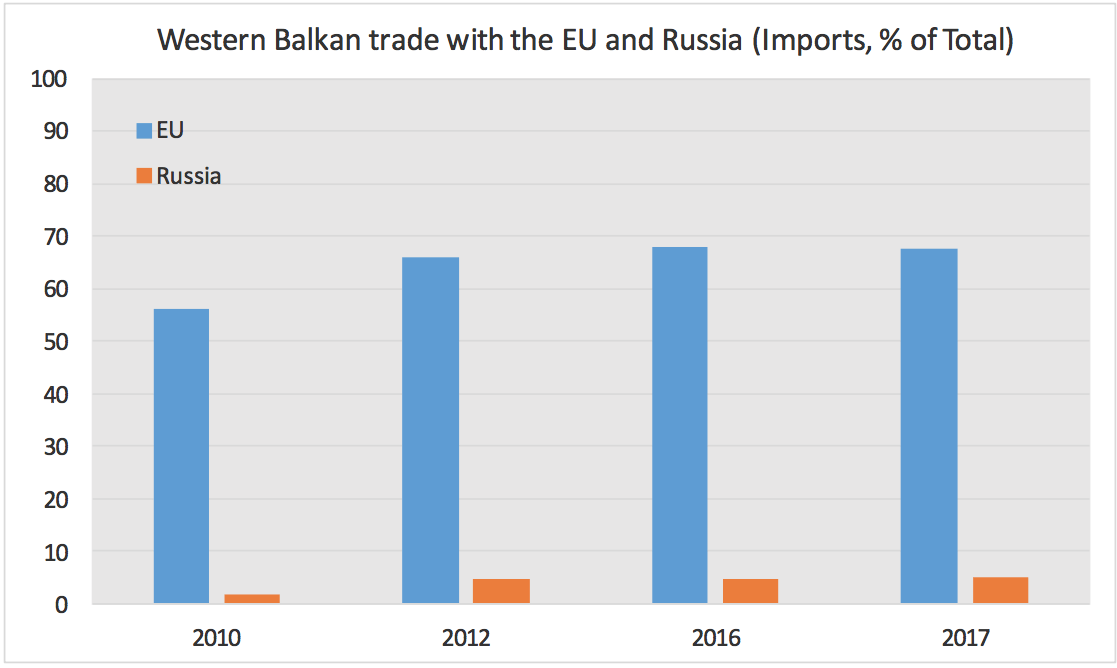

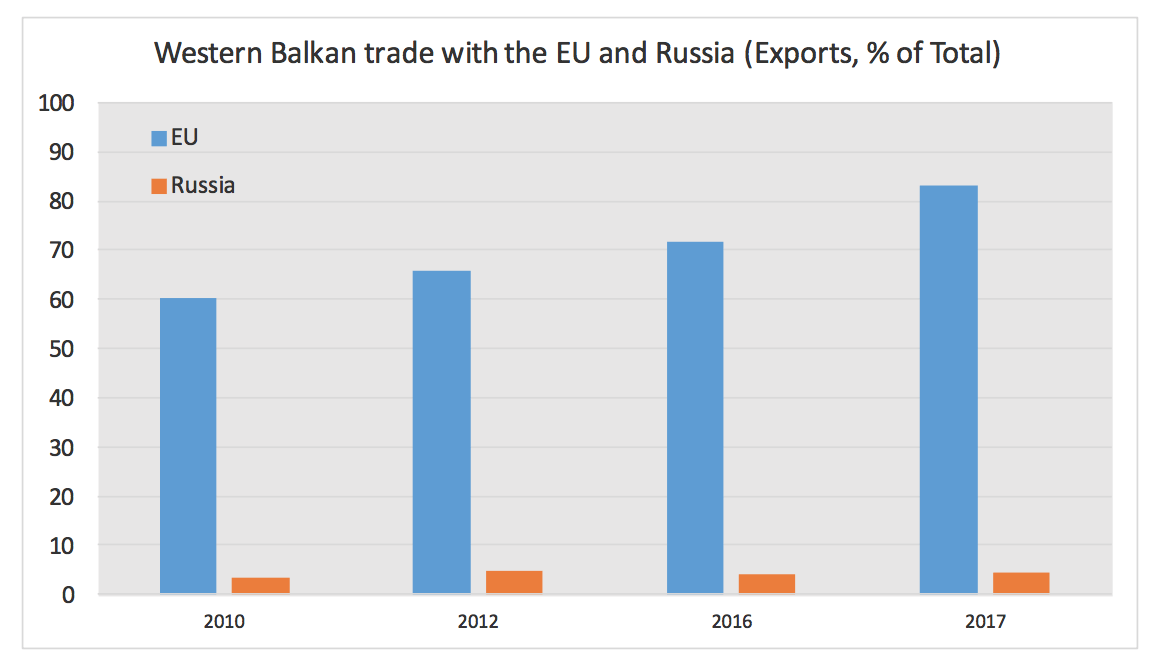

The European Union’s share of both total imports and total exports with the Western Balkans has consistently dwarfed that of Russia over the years. Figures for 2017 indicate that the EU accounted for 67.6% of the Western Balkan countries’ total imports, compared to Russia’s 4.8%. For the same year, 83.1% of total Western Balkan exports went to the EU and 4.3% to Russia. EU countries consistently rank in the top five export partners for all Western Balkan countries, with Russia lagging far behind (with the exception of Serbia, for which Russia is the fifth most important export partner).

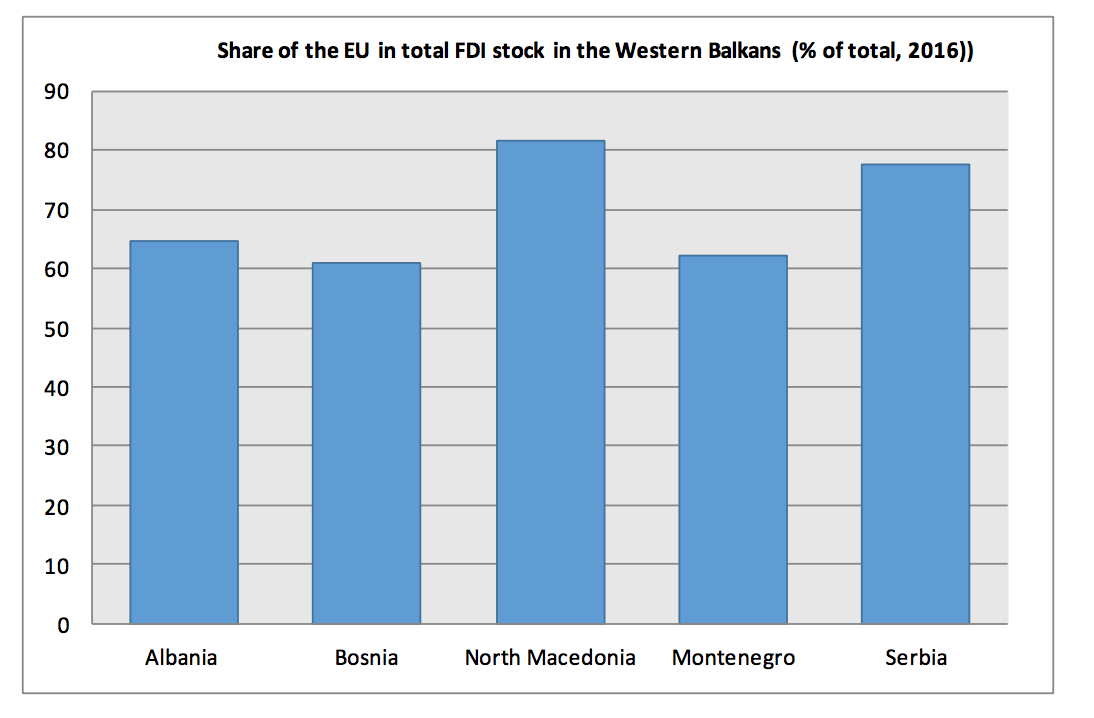

Similarly, foreign direct investment from EU countries continues to dominate total investment flows and stocks in the region. Even when the relative decline in investment activity in the region (during the early years of the crisis) is considered, in conjunction with the increase in total Russian investment over the past decade, Russia’s FDI still remains significantly lower than that of the EU member states. FDI flows and stock from EU countries have consistently accounted for between 60% and 80% of the total in all Western Balkan countries, with Germany, Austria, Italy, Greece, Cyprus and the Netherlands accounting for the lion’s share.

Perceptions and Reality in the Balance of Power in the Western Balkans

Clearly, while it is important not to underestimate Russia’s influence and role in the Western Balkans, it is also important not to overestimate it. Russia’s power and leverage in the region derives much more from sources of “soft power” (political and cultural diplomacy) than from hard economic leverage and substance. Other than the energy sector, Russia’s economic presence in the Western Balkans is dwarfed by that of the EU, even in strong allies Serbia, Montenegro and Republika Srpska.

However, in light of the current dynamic, the facts supporting the EU’s economic dominance are not enough to assuage concerns about the potentially destabilising impact of Russia’s policy in the region. Specifically, one can identify several reasons why the potential threat should not be underestimated, despite the European Union’s clear economic predominance.

First, although Russia’s economic footprint in the Western Balkan countries is clearly much smaller than the European Union’s, on many levels the perception of Russian strength is much stronger than the reality, and Russia leverages this to its advantage. There is a widespread feeling in the region that Russia’s economic contribution is far more important than it actually is.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

Destigmatizing Migration: A Different Perspective

The Decline of Debate and its Impact on Democracy

Colombia: A Divided Country in Search of Peace

According to a poll by the Serbian Investment and Export Promotion Agency, in 2016 a majority of Serbs believed that Russia was the biggest investor in their country, although Austria alone invested four times more than Russia. Russia has been able to spend less, but get more in the Balkans; the positive dividends it reaps are disproportionate to its real economic input. Russia has supported and fueled these misperceptions via the use of its media channels, playing the cultural solidarity card and successfully stoking impressions of a much stronger economic presence and contribution.

Second, despite being the overwhelmingly dominant force in the region, the EU’s public relations narrative has failed in connecting with the people of the Western Balkans and communicating to them the level and scope of the EU’s contribution to the economies of the region. For many citizens of Western Balkan countries, the European Union is often associated with strict and painful convergence criteria, impossible and unattainable reforms and endless delays in the accession process.

The EU’s technocratic approach and its weakness to connect with the people of the region− even as its money flows in to support national economies and projects such as improving governance standards and the rule of law and supporting media freedom, civic society and education– is potentially highly problematic.

Often, the EU’s loss in popularity among the Western Balkan population is Russia’s gain. According to a poll conducted by the Ministry of European Integration of Serbia in December 2017, 81 % of Serbs declared they do not know how much funding Serbia receives from the EU. In the same poll, when asked which countries have been the largest donors of international development assistance to Serbia in the period 2000-2016, 24% said the EU and 24% said Russia.

The reality is that, during this period, the EU had given 2,960 million euros (59.9% of the total) while Russia had given less than 0.5% of total developmental aid. Thus, it is clear that it is not enough for the EU to rest on its laurels and content itself with the reality of its dominant economic presence- it has to win the fight for perception as well. Therefore, a key challenge for the EU, if it is to leverage its tremendous economic involvement into political influence, is to change perceptions in the region to make its positive presence known and to promote a higher visibility of its constructive role.

Third, although Russia’s economic presence is much smaller than the EU’s in quantitative terms, its impact is strongest in areas that really matter in a region as complex and volatile as the Balkans. Over the years the Balkans have proven to be an unpredictable area where soft power, ethnic symbols and historic affinities sometimes matter more than current realities. Alternative facts are easy to perpetuate when supported by a narrative entrenched in ethnic, cultural and historical pathos.

In the power tug-of-war in the Balkans, Russia does not need to compete with the EU’s economic and political power directly, or have a strong presence in every Western Balkan country; it could suffice to cause just enough destabilisation and strife to derail the road to integration into Western institutions. Crucial examples of this approach are the support of separatist movements in Republika Srpska, which is sabotaging Bosnia-Herzegovina’s prospects of accession into the EU, as well as the perpetuation of the Serb nationalist narrative of “us vs them” (with Russia firmly in the “us” camp).

Photo Credit: David Parkins

To conclude, Russia’s agenda in recent years has been to deepen, broaden and consolidate its presence in the Western Balkan countries, using tools such as energy policy, cultural diplomacy, ethnic symbols and historical affiliations. Moscow has been able to seize an opportunity to capitalize on growing disappointment and disenchantment in the region during a period when the EU was focused on internal problems.

At the same time, while it is true that Russia’s economic power and presence cannot compare to that of the European Union, Moscow has succeeded in perpetuating the misperception that Russian involvement and contribution to the region is greater than it really is. Moreover, history has shown that Russia has the soft power and an allure that resonates, in varying degrees, across the region.

There is no doubt that, armed with its real energy dominance, its cultural solidarity rhetoric, its soft power tools, its divide-and-rule tactics and the promise of another alternative to being condemned to the EU’s waiting room, Russia can indeed pose as a real threat of destabilisation and disorientation in the region. This in turn will have a crucial impact in geopolitical and economic developments in the region, as well as on the future EU prospects of the Western Balkan countries.

In light of the shift in the geopolitical balance in the region, the prospect of EU membership for the Western Balkans is ultimately an investment in the EU’s stability and its very own political, security and economic interests and must be pursued with renewed vigour.

[1] The Western Balkan countries are Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.